“The art of architecture studies not only structure in itself, but the effect of structure on the human spirit”

Geoffrey Scott, The Architecture of Humanism, 1914

What would our built environment look like if we took our emotional, psychological and social needs today as the starting point for creating our surroundings? How would these invisible elements get translated and applied into visible, material form? Do we need a new set of tools and progressive approaches, responsive to 21st century patterns of life?

Making places that matter

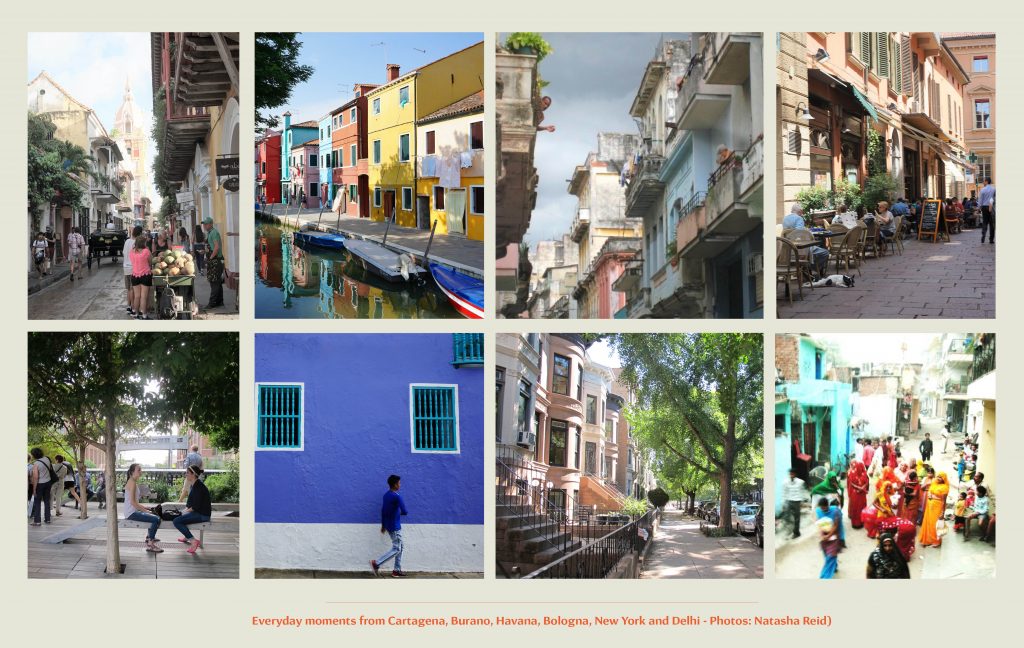

Through the sciences, and the work of the Conscious Cities movement, we know more and more about how our surroundings impact us; whether urban spaces, landscapes, buildings or rooms – their nature and quality all profoundly influence human wellbeing.

The places in our lives will shape our behaviours, perceptions, emotions, moods, sociability, feelings – even the sense of our identity1. There is growing evidence and awareness2 that if our surroundings are not actively enriching us, they are impoverishing us.

Despite the projection that more than two-thirds of the world’s population will be living in urban areas by 2050, buildings are currently produced with scant acknowledgement of the effects on people; often conceived as commodities to be sold rather than as habitats to nurture the human species that we are.

However the economic case for wellbeing is increasingly being recognised in development3, with greater evidence that places with a better “user experience” will be more economically valuable4, as well as better for people. There is widening industry interest in creating buildings and places that can “perform” well as human environments.

In the face of macro trends and accelerating changes to our everyday patterns of life, we need many new and varied forms of architectural practice that can responsively embrace and translate the complexity of human needs – both explicit and implicit – into built form.

“One of the great, but often unmentioned, causes of both happiness and misery is the quality of our environment: the kind of walls, chairs, buildings and streets we’re surrounded by.”

Alain de Botton, Architecture of Happiness. 2007

Translating emotional and social needs into built form

The convergence of built environment practice with neuroscience, psychology, and many more disciplines signals the advent of far-reaching, ground-breaking possibilities. Knowledge, insight and developments in the sciences open up significant opportunity for evidence-backed design that can demonstrably create targeted benefits and outcomes.

The topic of wellbeing is as broad-ranging as it is complex; with many frameworks5, indices and systems that capture a range of fields and perspectives, From the WELL buildings standards6, to the pillars of PERMA7 and high-level frameworks from Happy City8 and the Global Wellness institute9 to name only a few.

Looking forwards in practical application, we may be mindful of a path that sees wellbeing as something that can simply be achieved through the provision of features and elements. That is something that can be designed or reduced to component parts. Or that is corresponds only to one dimension or discipline.

In harnessing the work being done across a variety of fields, we need both a space for insights to converge and also a process to translate a wide range of research into coherent design approaches and solutions that can actively and effectively enrich our lives.

Three shifts for expanding practice

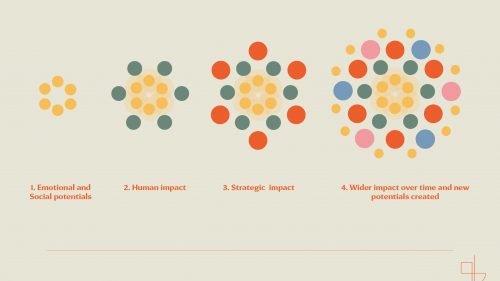

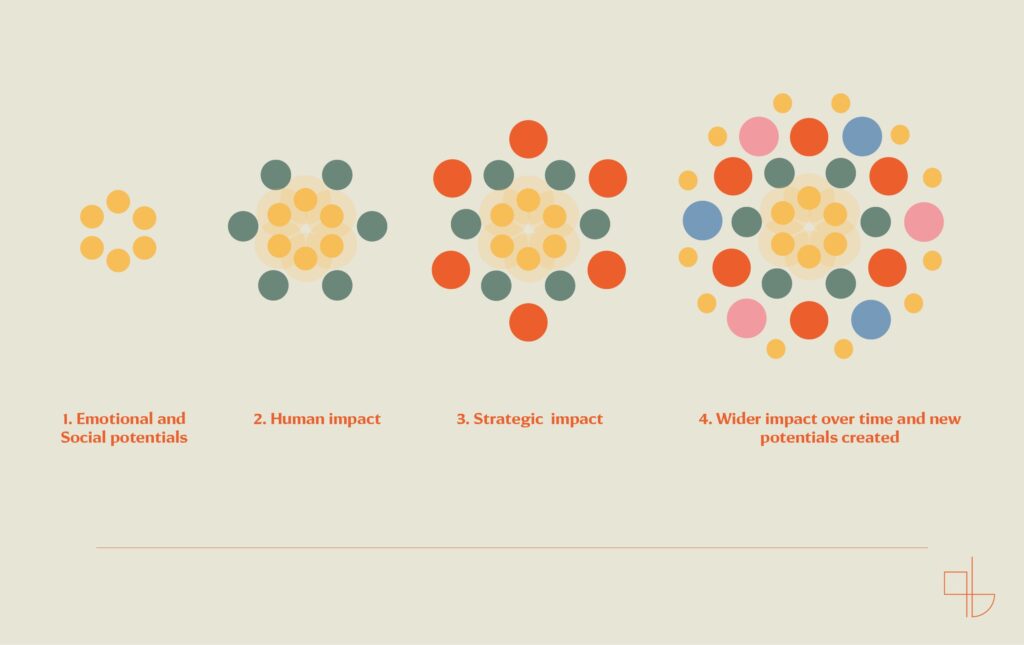

Through the lens of the emotional and social potential held in places, new approaches could be developed with the ability to incorporate and consider the complexity of human experience. Crosscutting frameworks could integrate a wide register of ideas and metrics of value, from mental wellbeing to Social Return on Investment10–from increasing connectedness, cohesion, social productivity11 and cultural vitality to creativity, joy and awe.

To build new tools and models that are responsive – or even compassionate – to a full spectrum and richness of experiences held within our built environment, we can look towards design thinking12, as a mode of operation that can integrate complex, contradictory elements and divergent ideas into synthesised solutions.

By shifting conversations and conventions, from the design of only built form, to the design of potential human impact, we could expande practice to the cultivation of value, for individuals, organisations, communities, businesses.

From the architecture of inert, physical matter to;

- The architecture of affect – design for human outcomes

- The architecture of integration – experience-led, evidence backed approaches

- The architecture of spatial systems – platforms for experiences and relationships

1. ARCHITECTURE OF AFFECT

Practice as the purposeful design for human outcomes

If we are to design for outcomes, then new metrics and values of “success” need to be defined – whether as individual practices, or as a collective, industry-wide endeavour.

The challenges lie in that quality of life, human experience, wellbeing and states of emotion are not “things” that can be determined through traditional design processes. Furthermore, each individuals experience of a place may be vastly different depending on their personal context.

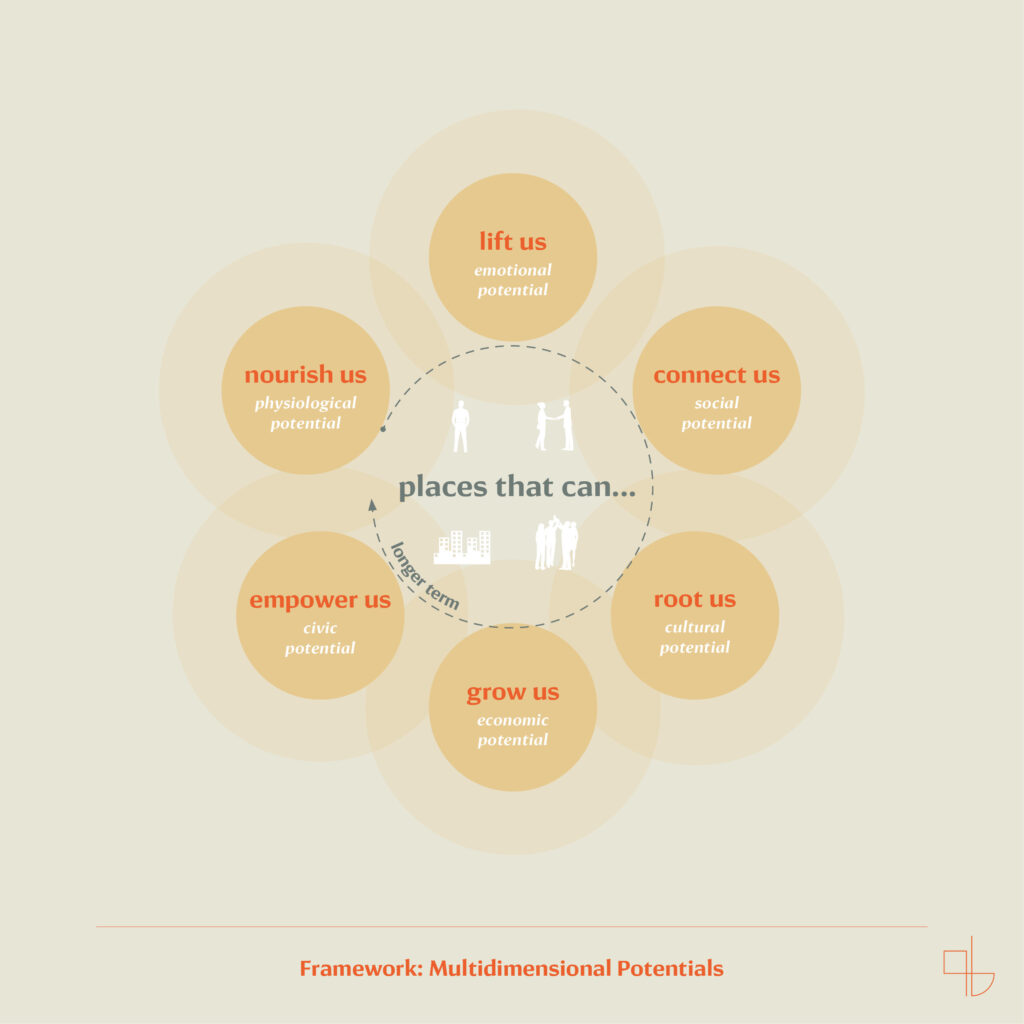

But conditions can be created where a range of positive changes can potentially emerge, through activity, use and encounter. We can create frameworks of “potentials” that give the freedom for different relationships between people and a place – evolved and cultivated over time. Design solutions could be conceived as springboards and platforms that enable multiple answers, rather than fixed, static containers.

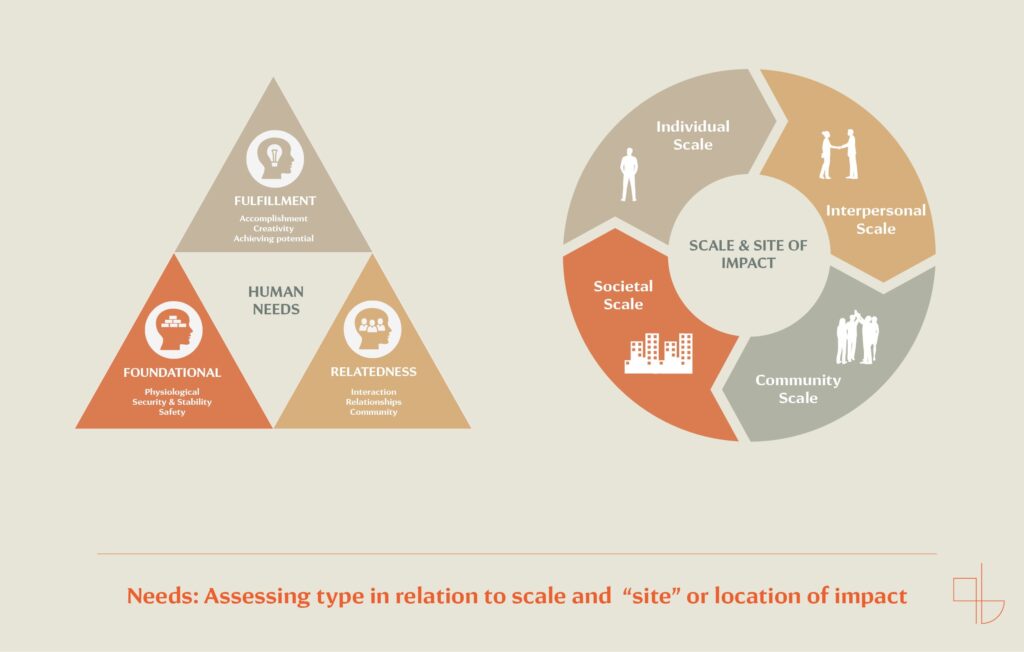

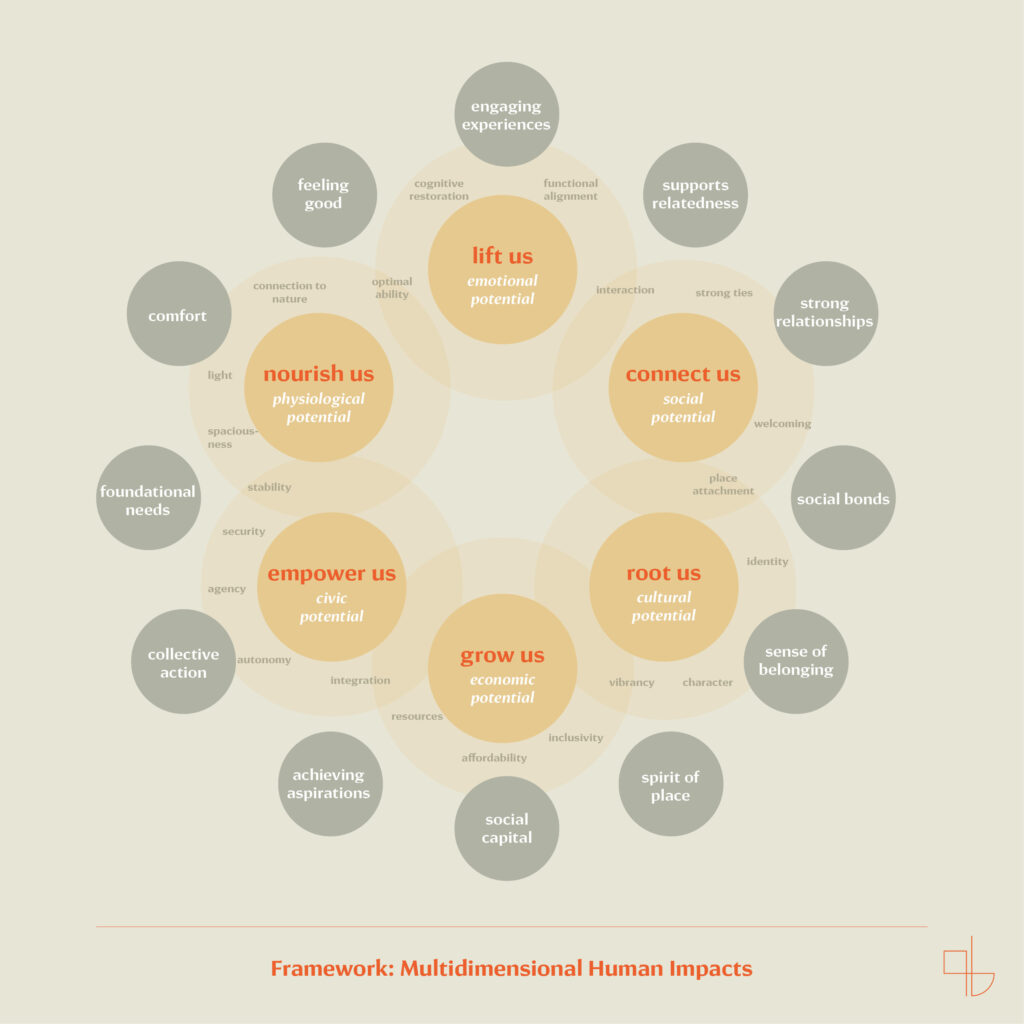

Through the process of developing an evolving methodology for practice, different ordering concepts have been considered, starting from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs13 and considering how places can impact our lives at different scales. From the individual to the collective – there are different “sites” or layers of intervention that feedback continuously to create a virtuous circle14 of sustained growth.

The framework sets out metrics of potentials, across several dimensions, reflecting the multifaceted social nature of place15 beyond its physical nature and enabling input from different domains and disciplines to be interwoven into clusters of action.

Looking at how our buildings, streets and cities can nourish us, lift us, connect us, root us, grow us and empower us – the sets of potentials are generative, rather than prescriptive. They could be developed into different metrics according to the project type and context;

Whether it is making everyday moments at home a little more joyful, enabling people to connect and be part of a community with a strong spirit of place, creating work environments that both energise us and allow us to focus for productivity and collaboration, public space projects that allow attachment and symbolic identity to be constructed, or interventions that can empower a neighbourhood.

2. THE ARCHITECTURE OF INTEGRATION

– experience-led, evidence-backed approaches

“Not everything that can be counted counts. And not everything that counts can be counted.” 16

For solutions to be meaningful to the people and place they are for, a check-list of “good wellbeing” features does not necessarily make a great place to be in, an inspiring building that moves us, or a well-loved neighbourhood. A mechanistic process of tick-box production would likely be at odds with an aim of generating enriching, delightful spaces that are full of life and possibility.

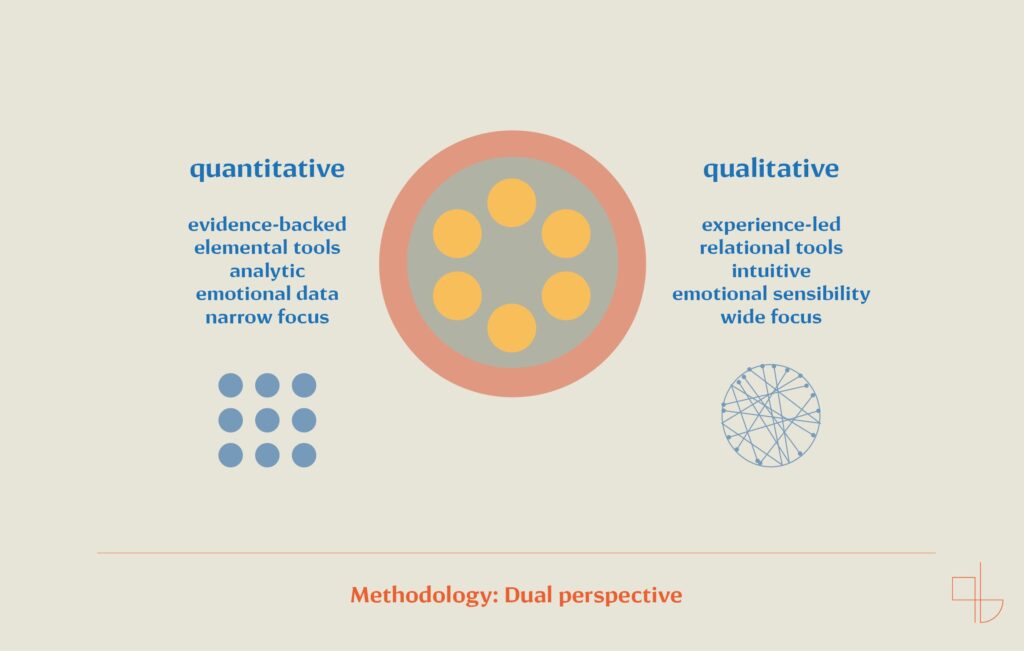

The opportunity here for practice is to translate multidisciplinary insights and integrate them laterally with experiential, intuitive and narrative-based understandings. To still consider big picture, wide-lens notions such as how a place becomes inscribed with meaning or memory, at the same time as focusing on targeted aspects like cognitive restoration for example.

New blended approaches – experience-led and evidence-backed – could be developed. Metrics could relate to everyday life in a way can is accessible to all, not only built environment professionals, researchers or academics. By overlapping qualitative and quantitative understandings, data-led metrics and subjective Key Performance Indicators could be gathered over time to map longer term and more complex impacts. For example;

- Does the place change a person’s mood and encourages them to stay longer

- Do they feel energised, inspired, restored, or able to think more clearly

- Has this created positive impact in wider areas (Ie. more effective at work)

- Has the place allowed people to personalise and inhabit it

- Do they feel a sense of ownership and attachment because of this?

- Do people have the opportunity to encounter others easily here

- Do they feel close to them and have they made new social connections as a result of spending time here?

3. ARCHITECTURE OF SPATIAL SYSTEMS – platforms for experiences and relationships

“Our buildings have lost their opacity and depth, sensory invitation and discovery, mystery and shadow. “17

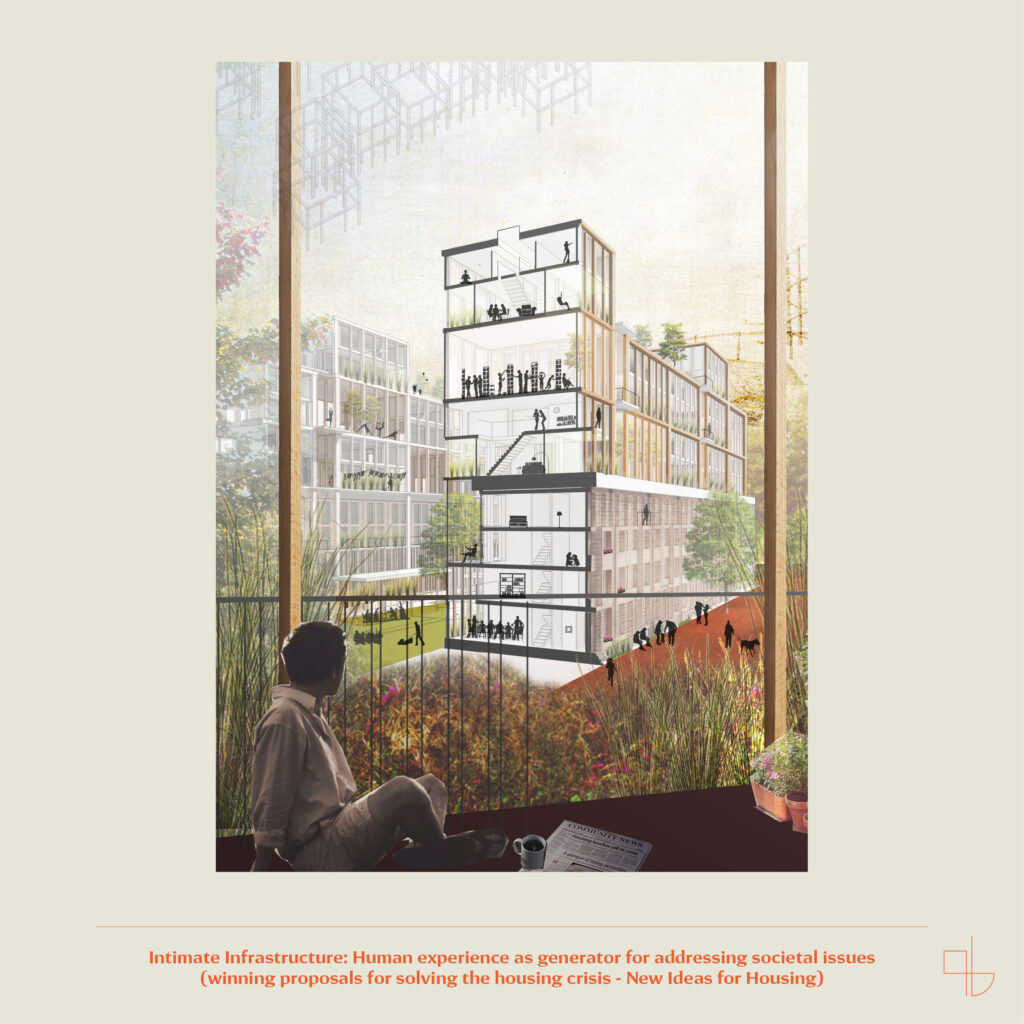

New blended approaches and value-systems would catalyse different types of architectural design process – emerging in line with the driver to create spaces that support life and growth. Instead of working with a single vision, a “top down” method, places could be developed starting from the person up – a microscale.

By conceiving a place as a sequence of desired emotions, perceptions, feelings, conditions, states, behaviours, interactions, flows, connections and relationships, a building’s form could grow from these overlapping aims, drivers, and mixed up components, to support diverse experiences and needs.

When imagining the design process as the choreography of experiences, atmospheres, spatial characteristics and conditions, the resulting organisation of physical matter would go beyond simply pleasing the eye. Buildings would instead be spatial systems and platforms for possibility that seed rich, multifaceted, adaptive places – solutions that can be greater than the sum of parts.

Future

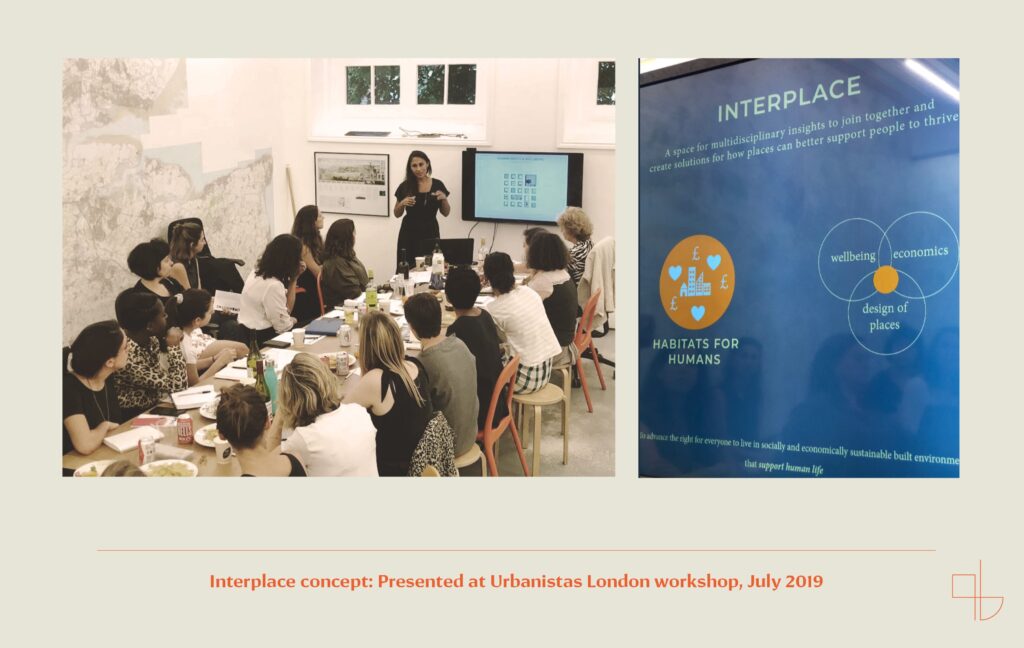

An early idea for a new type of “interface” practice model was shared at an Urbanistas London workshop, exploring the concept of connecting built environment practice, the sciences of wellbeing and economic domains. The workshop opened up discussion on how the strongest potential for impact and change is held at the very first stages of the development pipeline, when strategic brief are formed.

Through design, we have the capacity to solve problems, harness latent potentials and expand possibilities – exponentially so in concert with the sciences. When founded on deep understanding of our inner workings as human beings, we can radically shape our surrounding to better serve the needs of people, catalyse the potential for wellbeing and create holistic value across many spheres.

By pushing the boundaries of practice, taking progressive broad-minded approaches, we could shift the production of buildings as inert functional containers, to sources of growth, flourishing and value.

With so much opportunity ahead, why would we not create more life enriching places?

Not as the exception, but as the rule?

References

- 1 Goldhagen, S.W (2017) Welcome to your world. How the Built Environment Shapes our Lives. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. xxiii

- 2 Bond, M (2017), The hidden ways that architecture affects how you feel, BBC [website] http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170605-the-psychology-behind-your-citys-design (accessed 1st September 2019)

- 3 WPI Economics & British Land (2019), Design For Life. Integrating health and wellbeing into design and development

- 4 The Centric Lab. Sense of Place & Landmarks. The Centric Lab science library [blog]. https://www.thecentriclab.com/sense-of-place-landmarks (accessed 1st September 2019)

- 5 Happiness and Wellbeing Indices. Global Wellness Institute [website] https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/industry-research/happiness-wellbeing-index/ (accessed 1st September 2019)

- 6 WELL v2 pilot. The next version of the WELL Building Standards. WELL Certified [website] https://v2.wellcertified.com/v/en/overview (accessed 1st September 2019)

- 7 Seligman, M (2011): Flourish: A Visionary new Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. New York: Free Press. pp. 16-18

- 8 Brown, H, Abdallah S and Townsley R. (2017) Understanding local needs for wellbeing data. Measures and indicators. Scoping Report. Happy City and What Works for Wellbeing.

- 9 Global Wellness Institute (2018) Build Well to Live Well. Wellness lifestyle real estate and communities. Miami: Global Wellness Institute.

- 10 Nicholls, J., et al. (2012), A Guide to Social Return on Investment (SROI). The SROI Network.

- 11 RSA and British Land (2014), Developing socially productive places: Learning from What Works: Lessons from British Land. RSA and British Land.

- 12 Buchanan, R (1992) Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, Vol. 8, No. 2, (Spring, 1992), pp. 5-21. MIT Press.

- 13 Abulof, U (2017) Introduction: Why We Need Maslow in the Twenty-First Century. Society, Volume 54, Issue 6, pp 508–509. Springer US

- 14 Virtuous circle: a concept for a complex chain of events that reinforce themselves through a feedback loop leading to favourable results

- 15 Lefebvre, H (1991) The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell

- 16 Quote attributed to sociologist William Bruce Cameron

- 17 Pallasmaa, J. (2000) Hapticity and time: Notes on fragile architecture. The Architectural Review, Vol. 207, Issue 1239, pp 78-84

- 1 Goldhagen, S.W (2017) Welcome to your world. How the Built Environment Shapes our Lives. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. xxiii

- 2 Bond, M (2017), The hidden ways that architecture affects how you feel, BBC [website] http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170605-the-psychology-behind-your-citys-design (accessed 1st September 2019)

- 3 WPI Economics & British Land (2019), Design For Life. Integrating health and wellbeing into design and development

- 4 The Centric Lab. Sense of Place & Landmarks. The Centric Lab science library [blog]. https://www.thecentriclab.com/sense-of-place-landmarks (accessed 1st September 2019)

- 5 Happiness and Wellbeing Indices. Global Wellness Institute [website] https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/industry-research/happiness-wellbeing-index/ (accessed 1st September 2019)

- 6 WELL v2 pilot. The next version of the WELL Building Standards. WELL Certified [website] https://v2.wellcertified.com/v/en/overview (accessed 1st September 2019)

- 7 Seligman, M (2011): Flourish: A Visionary new Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. New York: Free Press. pp. 16-18

- 8 Brown, H, Abdallah S and Townsley R. (2017) Understanding local needs for wellbeing data. Measures and indicators. Scoping Report. Happy City and What Works for Wellbeing.

- 9 Global Wellness Institute (2018) Build Well to Live Well. Wellness lifestyle real estate and communities. Miami: Global Wellness Institute.

- 10 Nicholls, J., et al. (2012), A Guide to Social Return on Investment (SROI). The SROI Network.

- 11 RSA and British Land (2014), Developing socially productive places: Learning from What Works: Lessons from British Land. RSA and British Land.

- 12 Buchanan, R (1992) Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, Vol. 8, No. 2, (Spring, 1992), pp. 5-21. MIT Press.

- 13 Abulof, U (2017) Introduction: Why We Need Maslow in the Twenty-First Century. Society, Volume 54, Issue 6, pp 508–509. Springer US

- 14 Virtuous circle: a concept for a complex chain of events that reinforce themselves through a feedback loop leading to favourable results

- 15 Lefebvre, H (1991) The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell

- 16 Quote attributed to sociologist William Bruce Cameron

- 17 Pallasmaa, J. (2000) Hapticity and time: Notes on fragile architecture. The Architectural Review, Vol. 207, Issue 1239, pp 78-84