Back in 1954, two generations before Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bring Buildings to Life (2008) gave architects a glimpse of the restorative benefits of nature’s patterns in the built environment, an architect inquired:

What is the utility of a tree?

Richard Neutra, who posed the question in his landmark book, Survival through Design, may have not foreseen how, within a few decades of this incisive question, architectural features that promote health and wellbeing in the built environment would have to justify their inclusion in healthcare projects in return on investment (ROI) terms. Despite the undisputed evidence about how we thrive in natural environments, when it comes down to large urban construction, biophilic design features must justify their value or find external sources of funding.

Despite recognizing the inherent and inseparable relationship between man and nature down to its cognitive implications, Neutra did not merit so much as a footnote in the burgeoning Biophilia movement. Though Neutra coined the term Biorealism to capture his insight, neither E.O. Wilson’s book, Biophilia (1984), nor its subsequent volume, The Biophilia Hypothesis (1993), co-authored with Stephen R. Kellert, or even the emerging evidence-based design (EBD) movement reference his contributions.

In fact, Terrapin Bright Green’s white paper, The Economics of Biophilia (2012) is credited with revealing to both professional and general audiences the operational cost savings obtained from green spaces and biophilic features that enhance staff productivity and wellness. However, when Neutra published his seminal book, few now remember that he spoke against an arbitrary and false dialectic. He said:

Any doctrinaire division of the total concept into the aesthetic and non-aesthetic aspect would be artificial and cloud rather than clear the insight into this truly unified phenomenon.

Where does the utility of a tree stop and its beauty start? Our dualism has dangerously harmed, not helped, an understanding of design and of the architecture of a well-integrated environment.

The direct result is that harmful turmoil we know so well, that disintegration conspicuously spreading and sprawling around us in so-called civilized areas which are biologically blighted.”1

It is notable that Neutra did not describe this artificial division as one between utility and nature (or wellness or health). He chose the word beauty. If we take a long moment to consider this point, we find that our sense of beauty is so deeply rooted in the pattern language and rhythms of nature as to make both terms indistinguishable. Human health and wellness is immersion in nature’s beauty. However, the term beauty has long been caught in spurious debates about its supposedly subjective and capricious moorings.

Yet, there is a more profound and fundamental beauty that flows beneath the superficial currents of fashions and trends. The nascent field of neuroaesthetics seeks to study the neurological basis for our biological as well as cognitive resonance with the rhythms and interwoven web of activity that living systems orchestrate around us. Our sense of beauty, and the arts and crafts that have taken their inspiration from nature’s timeless patterns, speak of an underlying deep beauty where all life does converge.

In this essay, we propose that our health and wellbeing requires more than filling the built environment with curated spaces where nature may be on display. We propose that it takes expressive design that evokes a much more profound sentiment—in the words of the late Christopher Alexander, that the spaces we build breathe life into the dweller.

When we feel connected to the place where we dwell a profound cognitive transformation takes place, which the medical and psychological literature describe as Self-Transcendent Experiences (STEs). These experiences of emphatic integration reveal that we’re extraordinarily attuned to an implicit resonance between place and self.

We seek to explore the origins of deep beauty and how it can be cultivated by the skilled design professional to communicate that experience to others through his, her or their work. In the presence of deep beauty, health and wellbeing is but one of its many sweet and rewarding fruits. While the latest tools in eye tracking and imaging technology give architects and designers a closer look at how conscious awareness of place emerges, less has been uncovered of the creative process that shapes environments or artistic works steeped in deep beauty.

We know little about the cognitive methodology master craftsmen employed to erect memorable places or create transformational artwork. We propose that the search for meaningful and life-affirming design, which lies at the core of lasting physical and spiritual health, is found in the phenomenology of deep beauty. In this five-part series, we explore the roots of deep beauty and the implications for the design professional:

Origins

Part I – Self and Sense of Place

Part II – Deep Beauty—Embodied Kinship

Part III – Deep Beauty’s Cognitive Alchemy

Part IV – Unfolding Deep Beauty

Part V – Neuroaesthetics & Wholeness in Design

Origins

From the outset of human civilization, beauty has been recognized as an intrinsic attribute of nature—inseparable from its rhythms, symmetries, and patterns. It is not surprising that from earliest times, humanity’s need to create and share experience through art, ritual, and architecture has always done so with reference to the fundamentals of beauty emerging from nature. Certainly, while beauty is not synonymous with all art or built environments, its most memorable exemplars feature qualities that resonate across cultures, time, and place.

The reason for this universality of creative expression can be found in our biology. Evolutionary biologists suggest that Homo sapiens, like all living organisms, is beholden to habitat selection. This overarching theory suggests that organisms will occupy habitats where their fitness and ability to survive is maximized.2 In conjunction with another theory, niche construction, where organisms are said to modify their environment or create new ones due to their activities, affecting their evolution and that of other species, highlights the interdependence of complex ecosystems and how our health will invariably be linked to the fate of other species.3 Therefore, we relate and are drawn to that which extols the patterns and rhythms of the natural world; that which has shaped and links us to our genetic heritage.

However, scholars still question whether beauty is beholden to cultural mores or betrays a neurobiological footprint that underwrites culture. This debate has gained much traction in cognitive neuroscience, architectural theory, and the phenomenology of art.

Image Credit: African Savana by Thomas Bennie, Unsplash

According to a body of research from biology, environmental psychology, and anthropology, a consensus surrounds gene-culture coevolution as the most sensible framework by which the complex and highly plastic forebrain first evolved, and the creative arts flourished. Gene-culture coevolution details the web of causal explanations that link the long tail of genetic evolution to the malleable and accelerated pace of cultural evolution in complex and not always straightforward ways.

Eminent Harvard biologist and one of the leading proponents of the Biophilia Hypothesis, Edward O. Wilson, notes:

“Culture is created by the communal mind, and each mind in turn is the product of the genetically structured human brain… Genes prescribe epigenetic rules, which are the neural pathways and regularities in cognitive development by which the individual and mind assembles itself. The mind grows from birth to death by absorbing parts of the existing culture available to it, with selections guided through epigenetic rules [stable, non-genetic influences on gene expression] inherited by the individual brain…

“Culture is reconstructed each generation collectively in the minds of individuals. But the fundamental biasing influence of the epigenetic rules, being genetic and ineradicable, stay constant… As a consequence, the human species has evolved genetically by natural selection in behavior, just as it has in the anatomy and physiology of the brain.”4

In Wilson’s view, the distinctive qualities of the neocortex enabled our species to attain superior intelligence, language, and theory of self. Culture, he says “rising from the production of many minds that interlace and reinforce one another over many generations, expands like an organism into a universe of seemingly infinite possibility.”5

Humankind’s unique neurobiology and the social web of interactions bring us back to the arts and the nature of beauty, where Wilson says that “the epigenetic rules of human nature bias innovation, learning, and choice. They are gravitational centers that pull the development of mind in certain directions and away from others. Arriving at the centers, artists, composers, and writers over the centuries have built archetypes, the themes most predictably expressed in original works of art.”6

Nonetheless, Wilson notes that our species has paid a steep price for the cognitive edge our neocortex yields. This toll takes form as “the shocking recognition of the self, of the finiteness of personal existence, and the chaos of the environment. Homo sapiens is the only species to suffer psychological exile.”7

In his view, humans are the only species haunted by the past, consumed by the future, and driven by an unfettered imagination that generates, exalts, or questions its own agency. Wilson surmises that “early human invented the arts in an attempt to express and control through magic the abundance of the environment, the power of solidarity, and other forces in their lives that mattered most to survival and reproduction.”8

According to Wilson, “the arts were the means by which these forces could be ritualized and expressed in a new, simulated reality.”9 On the one hand, Wilson notes that faithfulness in the arts emerge from their adherence to human nature, to the emotion-guided epigenetic rules—the algorithms—of mental development. However, relegating art, and therefore beauty, to the exigence of survival and reproductive success ignores other equally essential aspects of human nature.

Humankind is also driven to physically dwell in places that are profoundly meaningful, rooting our collective identity and shaping our dreams and aspirations. The physical environment, both the local landscape and the sky that governs its ecology, are integral parts of our sense of community, agency, and collective purpose.

Design is the language through which we identify, embody, and experience the environment as part of our own individual, cultural, and spiritual identity.

Part I – Self and Sense of Place

Christian Norberg-Schulz, the Norwegian architectural scholar and phenomenologist, said that man can only dwell when he can orient himself within and identify himself with an environment that he experiences as life-affirming and meaningful.10 Since the earliest recorded forms of human expression, humankind has felt a deep need to determine its place in the universe. Mythologies of origin and the search for the Axis Mundi, the center of the world, are central elements shared by the world’s oldest civilizations.

While our ancestors experienced the struggle for survival during the day, nightfall offered the heavens, bejeweled with both distant and falling stars. Around the early fire camps that kept the unknown at bay, humanity sought meaning in the cyclical nature of cosmic phenomena. In many ancient civilizations, the highest point in the landscape, whether it was a Kilimanjaro or a Meru, the highest mountains were considered the sacred center of the world, the place where Earth meets Sky.

Eventually, architecture would become the nexus through which humankind could link both Heaven and Earth. In her book, Homo Aestheticus, Ellen Dissanayake, a scholar of evolutionary ethology, notes that our pattern-seeking drive hints at a neurobiological need to mark events by making things special. We don’t just gaze up at the night sky and see a million points of light—we see Orion, Cassiopeia, and Ursa Minor—ancient constellations that inform our Earthly mythologies, cosmologies, and world literature.

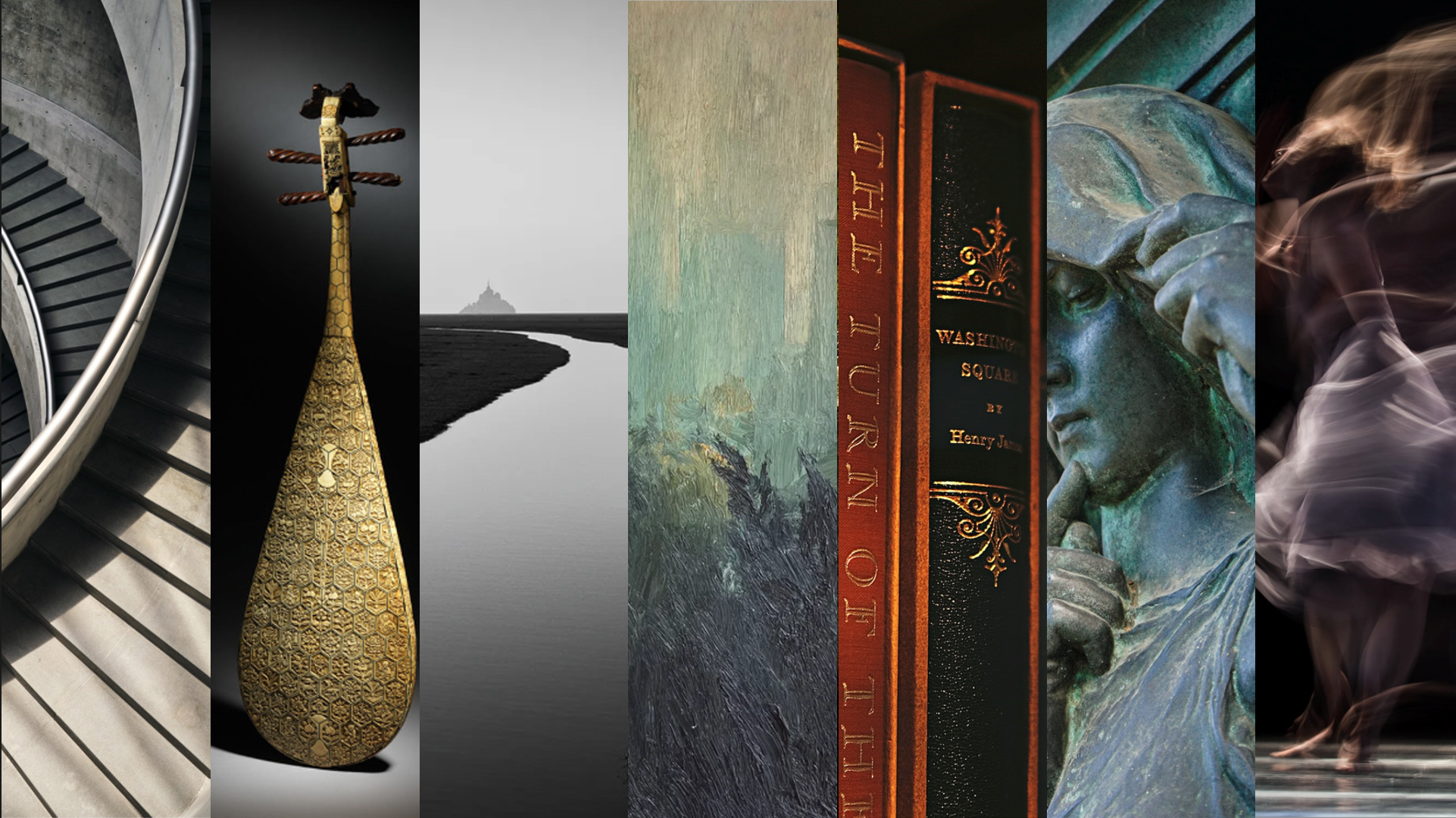

Image credit: Graphic by David A. Navarrete, assorted sources (Unsplash)

Dissanayake notes that while tool making and the ability to command symbols through language are conventionally seen as the most distinguishing of Homo sapiens, she argues that the Classic arts—painting, sculpture, architecture, music, dance, theatre, and literature, are also fundamental to our identity and agency.

The making of art, and the deep beauty we perceive in both the process, the ceremony, and the fruits of these creative endeavors, are not symbolic representations or sublimations of psychological phenomena. Art and ceremony, ritual and ornamentation are not simulacra of actual events or situations. They embody the distilled life experience of the artist and his or her environment.

While much attention is placed on art objects themselves as the remaining and tangible means through which we deduce our forbearers’ intentions, less attention is given to the process of making art. In fact, the latter may hold much more valuable information about the experience recorded by the artist, as well as the pre-cognitive process the observer undergoes when he or she experiences the beauty inherent in the art.

In his seminal book, Art as Experience, John Dewey says, “the career and destiny of the living being are bound up with its interchanges with its environment, not externally but in the most intimate way.”11 The process inherent in creating art is not only a recording of the artist’s experience, but also contains the cognitive pathway through which the observer is able to metabolize the experience of the artist in his own neurobiology.

Dewey says: “Art is thus preconfigured in the very processes of living… The distinguishing contribution of man is consciousness of the relations found in nature. Through consciousness, he converts the relations of cause and effect that are found in nature into relations of means and consequence. Rather, consciousness itself is the inception of such a transformation.”12 This observation would resonate half a century later in Richard Wollheim’s book, Painting as an Art, where he suggests that “painter and viewer share certain native perceptual capacities that are part of a uniform human nature, and that therefore during an aesthetic experience the perceiver actually reenacts part of the artist’s perceptual experience.”13

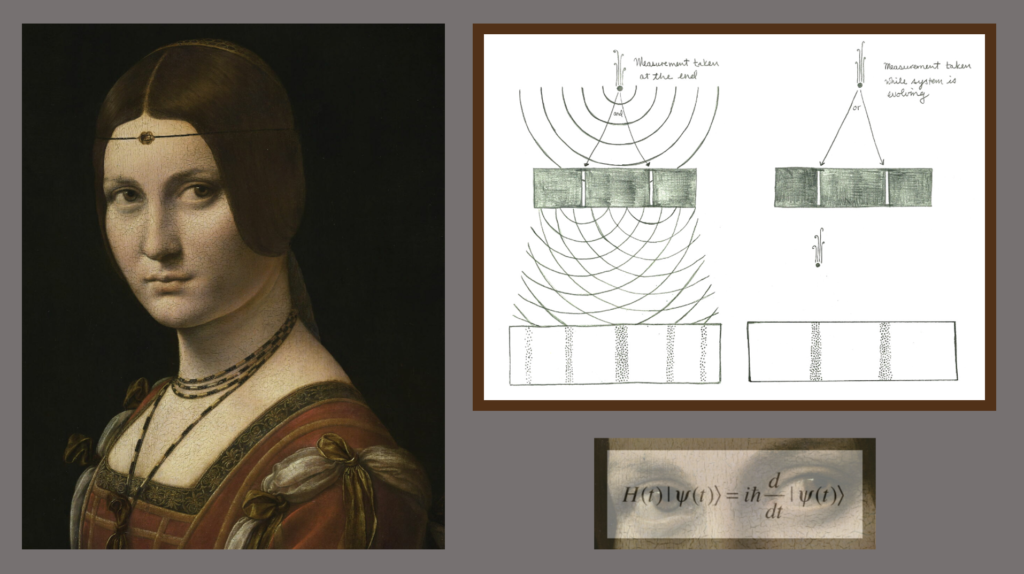

In fact, the notion that human consciousness, in the process of perception, reconstructs someone else’s embodied reality by mirroring the cognitive mechanics that gave rise to their experience of beauty has also vexed and marveled cognitive psychologists. However, the inescapable power of attention (through observation or measurement) to alter the behavior of a phenomenon or environment is well established in physics: where it is clearly understood that to perceive phenomena changes the nature of the observed behaviors.

In this light, beauty is not in the eye of the beholder, as much as in the perceiver’s ability to mirror that experience. To perceive is to re-enliven, metabolize, and galvanize. The perceiver alters the nature of the experience. The following example will cast light on the inherent power of perception in defining the nature of experienced reality.

Dating back to the early 19th Century, the world famous double-slit experiment in physics demonstrated that light was a wave. British polymath Thomas Young passed a light source through two closely spaced parallel slits in a screen. On the far side, against a secondary screen, he observed several bright bands of light. The interference pattern that appeared was akin to casting two pebbles into a pond and watching the ripples amplify or dampen each other’s peaks and troughs. Light, traveling through the parallel slits, behaved in similar fashion.

However, the experiment became more complex when, in 1924, French physicist Louis de Broglie, proposed that interference patterns might also be a property of quantum particles. Subsequent experiments by U.S. physicists Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer verified that the interference pattern originally seen with a light source could also be reproduced using electrons, even when the particles were shot at the double-slit screen—one at a time. In other words, particles (electrons or photons) exhibited wave-like behavior.

But, how could firing single particles generate an interference pattern when there were no other particles to interact with? The iterative process left no doubt about the implication. The astonishing discovery noted that elementary particles like photons could alter their behavior. This curious dichotomy—whether the photons exhibited wave-like or particle-like behavior—appeared to hinge on whether they were observed.

When a single photon is fired at two closely spaced parallel slits and is measured with a detector, a photon exhibits particle behavior. The photons impact the secondary screen like grains of sand pouring into a cavity. About 50% of the photons impact the screen directly across the first slit and the other 50% impact the screen directly across the second slit. As the two clusters of impacts grow, photons behave like discrete particles.

But when the scientists turn the detector off and forgo any measurement or observation, photons—fired one at a time, over the course of the experiment, generate the same pattern seen when light waves amplify or cancel out their peaks and troughs. Photons exhibit the interference pattern seen in the original experiment—wavelike behavior.

While the mathematics of the phenomenon are explained by the probabilistic nature of the wave function, there are many theories as to why setting out to detect or observe dynamic particles alters their behavior. However, the fact that observing modifies the object of observation reveals that perception is an active agent in molding what we see.

Our sensory and motor faculties, which we use to perceive and navigate through space, share the same neural infrastructure that higher cognitive faculties like attention, memory and planning use to process sensory stimuli. Therefore, this two-way pathway that enables us to make sense of our environment also allows the attributes of a place—its atmosphere—to color our perception. Neuroscientists have discovered that “the brain, far from being a fully formed and immutable organ by adulthood, could show dramatic physical responses to environmental changes all through the lifespan.”14 In fact, studies have found that “those who were raised in or live in large cities show larger brain responses to social triggers for anxiety than those living in rural settings,” 15 which notes the short and long-term impact our surroundings have on self-perception, impacting both our formative years as well as our daily social outlook. In a very real sense, the ancient texts from the Upanishads were prescient when they note that what we see, we become.

Image credit: RMN, Musée du Louvre; graphic by David Navarrete, Unsplash

And this fact strikes at the core of the symbiotic relationship that makes human perception indivisible from the environment. Architectural scholar Christopher Alexander has astutely pointed out that the two slit experiment in physics demonstrates that the geometry of design—whether in a physics experiment or the built environment—impacts the behavior of the elements within that space, including perception. In his view, the wholeness of a system is sensitive to any disruption to its internal symmetry.

In his book, A Beautiful Question, Finding Nature’s Deep Design, Nobel Laureate in Physics Paul Wilczek, notes that “if we take the Universe in space-time, unfolded to yield a ‘God’s-eye’ view of reality, to be fundamental, we are led to a modern form of Parmenides’s changeless One. The great twentieth-century mathematician and physicist Hermann Weyl […] put it this way, in what I think is among the most beautiful, as well as most profound, passages in all of literature:

‘The objective world simply is, it does not happen. Only to the gaze of my consciousness, crawling along the lifeline of my body, does a section of this world come to life as a fleeting image in space which continuously changes in time.’ ”16

This observation that the phenomenal world is, rather than happens, betrays a profound insight. It reveals that space-time, the temporal and spatial changes we experience in our awareness, are a function of a change in human perception rather than independent of it.

Hence, looking at the mechanics of perception through a scientific lens, whatever sensory stimuli modulates our cognitive faculties also modulates our perception of reality. If the so-called hard sciences like physics and mathematics recognize the primacy of perception in shaping the world we inhabit, what does their synthesis reveal about the origin of beauty and the impact of architecture—the geometry of design—on human consciousness? By the same token, how does design alter and modify our sense of self, our ability to imagine and recall memories, or even our willingness to share and change?

In this light, the physical sciences might be one up on the humanities by tipping the balance in favor of the fundamental structures of both nature and human perception as the underlying mechanism that generates the universal experience of beauty. For the most part, Western philosophical thought and aesthetic theory have framed beauty’s origin as a relative problem of definition and taxonomy. However, nature’s deep beauty, as well as humankind’s recognized exemplars in the arts, reveal that the geometry of their design is a powerful cognitive tool. Design, as expressive form in every sensory capacity, engages in the observer in the same process of cognitive unfolding that the artist intuitively explores in the process of unveiling beauty’s mysterious alchemy through the artistic work, craft, or display of skill and experience.

Therefore, approaching beauty as a concept or abstraction renders it a subjective experience beholden to relative values rather than underwritten by a biological or even cortical framework streamlined by humankind’s millennial exposure to nature. By exploring the neural and chemical roots of the aesthetic experience of beauty, we seek neurological evidence of the underlying mechanisms that reveal humankind’s universal experiences of self-transcendence when exposed to expressions of deep beauty.

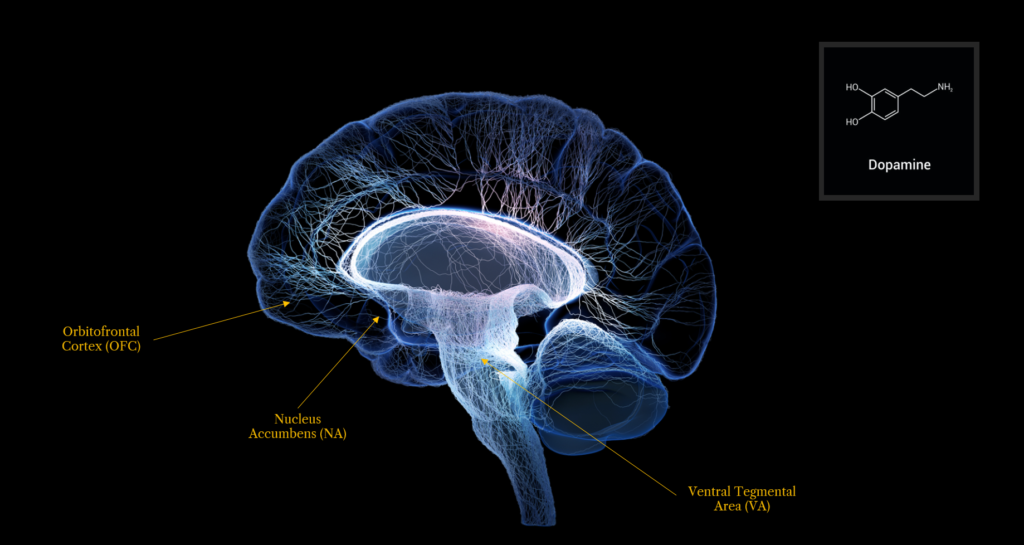

This search has led researchers to study how the brain recognizes, rewards, and reinforces positive experiences of beauty. The brain’s pleasure center or hedonic circuit lies at the center of this investigation because deep beauty generates a recognizable pleasure response in the observer. Neuroimaging studies have found that beyond beauty’s discernable neurological footprint, there is “an electrical and chemical network shared by a host of other pleasurable activities—everything from maternal love to enjoying a piece of chocolate.”17

Studies have found that “the perception of beauty is strongly motivated by emotional and subcortical activities in the limbic and brainstem areas.18 Therefore, exploring the emotional and physiological underpinnings of our hedonic experiences reveal how the pleasure we reap from the experience of beauty share a common cortical lineage.

Functional MRI studies in particular have revealed that the Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC), working in tandem with the Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC), act as the primary nexus for sensory integration, emotional processing, and hedonic experiences. In this regard, Harry F. Mallgrave notes, that “pleasure in a biological sense is not a sensation, but is rather the outcome of a system that, in response to environmental stimuli, evaluates and codes the subjective and emotional valence of pleasurable or unpleasant experiences.”19

In other words, pleasure is a learned response based on previous experience rather than a sensory reflex to external stimuli. Martin Skov, a Danish neuroscientist, notes that a series of specialized circuits that begin in the Ventral Tegmental Area (VA) of the brain stem and pass through the Nucleus Accumbens (NA) and the OFC compute the reward value of a stimulus, which in turn provokes activity in the insula. The fuel for this activity is dopamine, a neurotransmitter that controls the brain’s reward and pleasure centers by regulating emotional centers.20

Image credit: Cortical render, Unsplash; graphic by David Navarrete

According to Mallgrave, the fact that a work of art engages these cortical networks underscores the essential role that emotion preconsciously plays in all aesthetic experience. When our physiology is exposed to environmental stimuli that our brain and sensory processing systems recognize as matching past life-affirming experiences, the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) unleashes a chain of chemical and neural reactions that soon well up in our awareness as perceived emotion. And while the intensity with which expressive form, through design, differs from person to person, it remains a significant and widespread experience across time and cultures.

And though the intensity of art’s imprint may vary from the momentary to the indelible, our perception is such that it can even register as commonplace in the perception of the same person once or multiple times while, under different circumstances, remain with us for a lifetime. Despite the fluid and unpredictable nature of its perceptual alchemy, its universal appeal is reaffirmed by its inherent cathartic power, whether on display in religious, secular, or cultural venues, the arts give sensory life to our deepest feelings and emotions, individual and collective. Therefore, our emotions and the meaning attached to expressive form through art and design remain the indelible evidence of deep beauty’s imprint on human perception.

Such realization may be what led Francis Bacon, one of the founding fathers of the scientific method, to observe—beauty itself is but the sensible image of the Infinite. We now know that behind the experience of beauty lies a vast cortical labyrinth of processed stimuli that generates one of the most sublime cognitive states that our psycho-physiology can sustain.

Deep beauty makes sensible that which we intuitively recognize embodies infinity and wholeness, attributes of human consciousness that we can cognize through direct experience. Juhani Pallasmaa says “artistic images seem to address directly our existential sense, and have their impact through our bodily being, before they are cerebrally registered or understood. An artistic work may have a forceful mental and emotional impact, yet remain forever without an intellectual explanation.” 21

Next: Part II – Deep Beauty’s Embodied Kinship

Image credit: Pedro Lastra, Unsplash

References

1 Richard Neutra. Survival Through Design, (New York: Oxford university Press, 1954), 79.

2 Rosenzweig, Michael L. “A Theory of Habitat Selection.” Ecology, vol. 62, no. 2, 1981, pp. 327–35. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1936707. Accessed 30 Aug. 2024.

3 Edward O. Wilson. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), ?

4 Ibid, 127.

5 Ibid, 223.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid, 224.

8 Ibid, 225.

9 Ibid.

10 Christian Norberg-Schulz. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1979), 5.

11 John Dewey. Art as Experience, (New York: The Berkeley Publishing Group, 1934), 12.

12 Ibid, 25.

13 Ellen Dissanayake. Homo Aestheticus: Where Art Comes From and Why, (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1995), 5.

14 Colin Ellard. Places of the Heart: The Psychogeography of Everyday Life, (New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2015), 117.

15 Ibid., 128.

16 Paul Wilczek. A Beautiful Question: Finding Nature’s Deep Design, (New York: Penguin Books, 2015), 116.

17 Harry Francis Mallgrave. Architecture and Embodiment: The Implications of the New Sciences and Humanities for Design, (London and New York: Routledge, 2015), 46.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid, 47.

20 Ibid, 48.

21 Juhani Pallasmaa. The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture, (West Sussex, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 64.