Introduction

Home is a feeling. Whether temporary or permanent, homes carry emotions, memories, and a sense of deeper attachment. It is hard to argue that non-traditional temporary homes are becoming common and are continuing to evolve with the needs of modern societies. However, significant emphasis is still placed on owning permanent homes, often overshadowing the needs of those living in temporary ones.

Millions of people move every year and find themselves settling into different cities or neighbourhoods1. The reasons for this mobility can be varied, from urban regeneration, life events, better prospects, to domestic and international migration, poor socio-economic conditions, or housing dissatisfaction1,2-4. During this constant move for stability, the meaning of home becomes elusive. People tend to lose a sense of home and instead seek solace in the search for their next home.

People find it difficult to make a temporary house their “home,” and thus creating a sense of “home” within a temporary house is often a challenge. Temporary housing comes with limitations and restricted options for personalization and adjustments, such as rules like no nails on the walls. In many cases, transient homes prevent refugees or homeless people from fully integrating into their spaces, including something as simple as inviting visitors5. These constraints highlight the lack of control and autonomy experienced by temporary residents.

Furthermore, people living in temporary housing are hardly involved in the design of their homes. These temporary dwelling units are often designed in a very similar manner, despite the residents belonging to highly diverse socio-demographic groups2. Moreover, temporary residents mostly settle for the first available home and have fewer choices. As a result, people not only lack decision-making but are also unable to fully customize their homes. These homes thus need to be more adaptable and flexible, capable of addressing the immediate and evolving needs of the constantly changing residents2,6.

This article aims to create awareness about the importance of the well-being of the residents of temporary housing. It further aims to explore the ‘meaning of home’ and place attachment experienced by people living in these temporary homes. Furthermore, the article investigates the considerations and decision-making approaches that can enhance the well-being and attachment of these residents, improving their overall quality of life.

Temporary Housing typologies

Temporary homes encompass a wide range of typologies, addressing housing needs across various demographic and situational contexts. These categories can broadly be classified into short-term and long-term rental housing, individual and collective student accommodations, hostels, co-living, and shared spaces that provide affordability, flexibility, and basic living arrangements. The concept of transient housing also extends to nomadic housing, including mobile homes and extended-stay hotels and B&Bs, which cater to populations requiring flexible and sometimes location-independent stays.

Other forms of temporary housing serve populations in crisis or transition, such as shelters and hostels for refugees and asylum seekers, which provide immediate and essential housing conditions for homeless individuals6. Similarly, disaster relief housing is provided in response to natural disasters and offers urgent, short-term accommodations for affected individuals and communities. Each of these temporary housing typologies plays an important role in accommodating diverse populations and responding to temporary housing needs.

With such a variety and complexity of situations, it is evident that the psychological experiences and perceptions of these typologies are significantly different in addition to the physical aspects of the homes. People residing in these temporary housings often come from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, with diverse needs and behaviours and often unmet unique needs. However, while the institutionalized approach of designing temporary housing in a standard way has been seen as the ultimate solution, it is found to be rather dissatisfying2,7.

It can thus be highlighted that there is a need to develop more thoughtful approaches to temporary housing, in a way that positively affects the mental health and well-being of residents. To support residents in a better way, it is also crucial to analyse and understand the aspects of the meaning of home, emotional attachment, and well-being in the context of temporary housing.

Meaning of Home

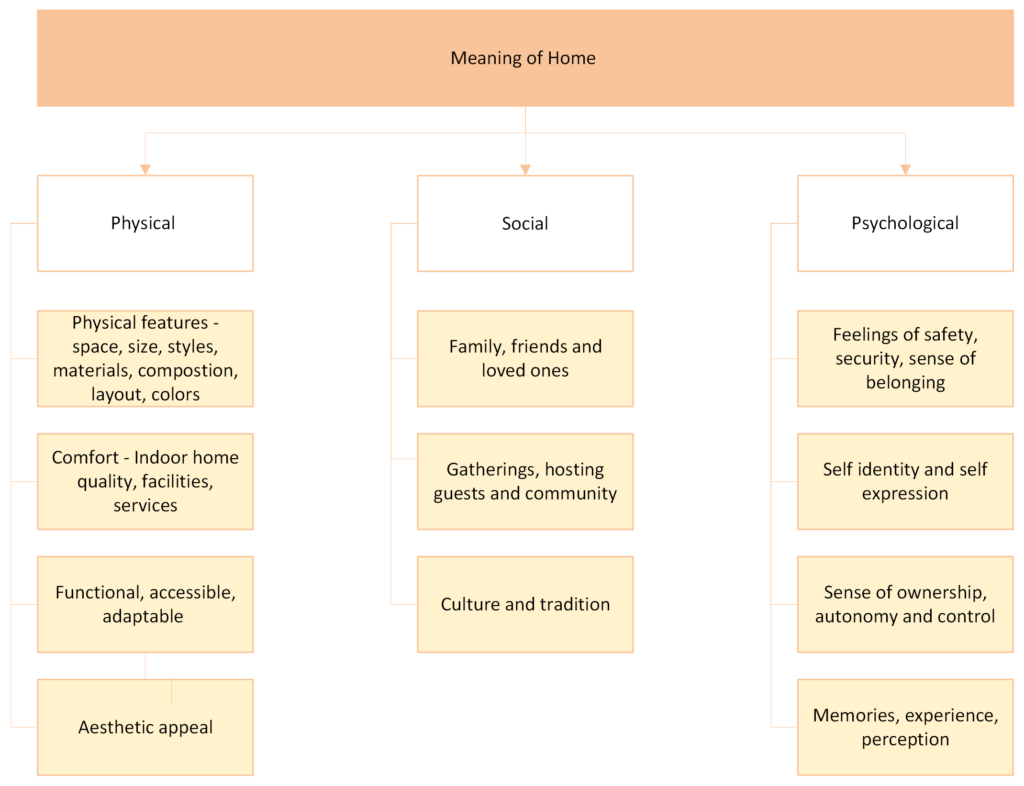

The meaning of home can be different for different people, from home being a safe place, a shelter or emergency stay to it being a space to socialize, be and express oneself3. Taking into consideration the tripartite framework, a home can be seen as an amalgamation of physical, social and psychological meanings8.

For some people the meanings are more about comfort and physical features and for others, it is rooted more in social dimensions8,9. The physical meaning of a temporary home caters to the physical entity and features, from architectural style, materials and colours to physical properties of indoor home quality, comfort, function and services. Home is also an extension of social life for many people – pertaining to their relations and how they spend time at home with their friends and family. Home is also seen as an entity expressing generational traditions and culture.

Considering the psychological realm, a home is also a reflection of one’s personal self – replicating the feelings of happiness, safety, security and a sense of belonging. Furthermore, familiarity, experience, memories and a sense of belonging are found to be connected to people’s identity, leading to expression of their artistic self in their homes2,8,10.

Additionally, behavioural habits, effective facilitation of activities and flexibility in spaces aid value to homes3,11. The ability of appropriation and control of making changes to the dwelling also develops feelings of attachment and sentimental value to the homes. This layered understanding of ‘Meaning of Home’, showcases the multifaceted nature of home and its significance in shaping both individual and collective well-being.

Place Attachment and Wellbeing

People develop attachment to places through emotional connections as well as through physical and social interactions resulting from direct engagement with their environment12. This attachment is influenced by various factors, including the physical characteristics and quality of housing, which significantly impact the well-being and sense of connection of the residents13. Features such as safe neighbourhoods, safety, security, privacy, and good lighting positively influence attachment to place, further enhancing the well-being of residents10. When there is a lack of physical comfort, people often connect with their homes through homemaking, embracing cultural norms and social inclusion9.

The sense of place and attachment are strongest with home ownership due to autonomy and control that people can exert over a place. However, these feelings are also vital in the less explored context of temporary accommodation. Even in temporary housing, individuals attach meaning and emotions to a home, positively impacting their self-worth and sense of belonging14.

People living in good-condition, long-term rentals tend to exhibit stronger attachment and connection to their homes12,14. Tenure is hence found to play a critical role in fostering well-being. Additionally, the satisfaction of basic psychological needs such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness has been proved to contribute to positive mental health, increasing resilience and overall psychological well-being5.

Given the profound influence of place and place attachment on well-being, it is important to study the specific needs and requirements of temporary residents. By understanding these factors, we can design environments that foster emotional connections, support life satisfaction and enhance quality of life in temporary housing.

Needs and Design considerations

As mentioned earlier, the meaning of home could be different for different people, and the needs of a diverse group of temporary residents cannot be defined uniformly. However, evidence shows that even small changes in design can significantly impact how people perceive and connect to their temporary homes. It is not only important to consider the physical form of these temporary dwellings but also the psychological aspects of the home as associated by the residents.

Privacy and safety are fundamental to any home. Even small additions, such as a door lock, can enhance feelings of privacy and territoriality, helping individuals feel more connected to their space14.

The physical environment plays a crucial role in the concept of home. It influences how people interact with their space, express themselves, and create meaning8. Factors such as space size, indoor environmental quality (air, light, comfort), and overall health and well-being4 are critical considerations.

The act of homemaking is vital for attachment to temporary homes. As new residents personalize their spaces by adding objects or functions, they layer their own identity over the previous occupants, strengthening their connection to the space2,15. Personalization, such as adding wallpaper, painting, or simply the ability to make small changes, can significantly enhance feelings of attachment. The presence of features like fireplaces, which have historically been centres for emotional bonding, also contributes to this process14.

Small design additions, such as a kitchenette or heating or cooling facilities, have been found to help create a sense of homeliness for residents in extended stays15. Additionally, the ability to host guests and engage in social activities within adaptable spaces, enhances residents’ sense of community and belonging3,5.

Design considerations that cater to daily habits, cultural practices, and community integration strengthen place attachment and contribute to well-being9. Providing spatial freedom, access to necessary facilities, and opportunities for personal expression along with suitable physical aspects, all contribute to the meaning residents associate with their temporary homes.

Conclusion

Temporary housing is often criticized for its constraints, restrictions, and lack of flexibility. However, existing research clearly indicates that increasing adaptability and flexibility within these spaces can foster a stronger sense of home and enhance the wellbeing of the residents.

The no-nail rule often imposed in temporary accommodations restricts residents from personalizing their spaces, making it difficult for them to truly feel at home. While maintaining the physical condition of the property is important, allowing temporary residents some flexibility – such as drilling a few holes, painting the walls or implementing alternatives that do not damage walls permanently, could strengthen their sense of ownership.

Rules and regulations that give residents more control over their living spaces can foster a stronger connection to their homes. As highlighted, the lack of autonomy and control in the home-making process not only negatively impacts the residents’ ability to express their identity but also decreases their ‘self-worth’14. Empowering residents in a way that can contribute positively to their overall well-being and sense of belonging is definitely essential.

With thoughtful design and policy considerations, landlords, rental agencies, and residents can achieve mutually beneficial outcomes. It is important to note that future research should prioritize understanding the varied needs and requirements of the residents including their psychological needs, situational contexts, socio-economic demographics, and neighbourhoods where temporary housing is being developed. It is also essential to carefully study the diversity of residents for design and policy implementation. Moreover, incorporating the aspects of the meaning of home, community and place attachment, in addition to emotional connections within these spaces can significantly enhance the well-being and improve the overall quality of life of the residents of these temporary homes.

References

- Wolbring T. Home Sweet Home! Does Moving Have (Lasting) Effects on Housing Satisfaction? J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(4):1041-1062. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9755-7

- Overtoom M, Elsinga M, Bluyssen P. Experiencing Temporary Home Design for Young Urban Dwellers: “We Can’t Put Anything on the Wall.” Buildings. 2023;13(6):1318. doi:10.3390/buildings13061318

- Overtoom M, Elsinga M, Bluyssen P. Towards better home design for people in temporary accommodation: exploring relationships between meanings of home, activities, and indoor environmental quality. J Hous Built Environ. 2022;38(1):1-27. doi:10.1007/s10901-022-09947-z.

- Overtoom M, Elsinga M, Oostra M, Bluyssen P. Making a home out of a temporary dwelling: a literature review and building transformation case studies. Intell Bldgs Int. 2018;11(1):1-17. doi:10.1080/17508975.2018.1468992.

- Albers T, Ariccio S, Weiss LA, Dessi F, Bonaiuto M. The Role of Place Attachment in Promoting Refugees’ Well-Being and Resettlement: A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):11021. doi:10.3390/ijerph182011021

- Busch-Geertsema V, Sahlin I. The Role of Hostels and Temporary Accommodation. Eur J Homelessness. 2007;1(1):67-93.

- Thomsen J. Temporary Accommodation Dissatisfaction. Urban Stud. 2007;44(4):889-912. doi:10.1080/00420980601184700

- Sixsmith J. The meaning of home: An exploratory study of environmental experience. J Environ Psychol. 1986;6(4):281-298. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(86)80002-0

- Kellett P, Moore J. Routes to home: Homelessness and home-making in contrasting societies. Habitat Int. 2003;27(1):123-141. doi:10.1016/S0197-3975(02)00038-9

- Mehta M. Memory Laden Mini-Neighbourhood: An Age-Friendly Place Embraced with Attachment and Feelings. Unpublished Thesis. 2020.

- Marcus C. House as a Mirror of Self: Exploring the Deeper Meaning of Home. Jung Inst Libr J. 1995;17:1-24.

- Wächter L. Beyond Permanent Residences: Measuring Place Attachment in Tempo-Local Housing Arrangements. Urban Sci. 2024;8(2):173. doi:10.3390/urbansci8020173

- Clapham D, Foye C, Christian J. The Concept of Subjective Well-being in Housing Research. Housing Theory Soc. 2018;35(3):261-280. doi:10.1080/14036096.2017.1348391

- Harris E, Brickell K, Nowicki M. Door Locks, Wall Stickers, Fireplaces: Assemblage Theory and Home (Un)Making in Lewisham’s Temporary Accommodation. Antipode. 2020;52(2):421-442. doi:10.1111/anti.12598

- Lewinson T. Residents’ Coping Strategies in an Extended-Stay Hotel Home. J Ethnogr Qual Res. 2010;4:180-196.