I grew up in Beijing, and have always lived in or near the center of the city. I have also always loved books, and my most visceral contacts with books were in the Xidan Books Building. True to its name, it was a huge, multi-floored building of books carefully arranged on shelves stacked in matrices. I spent a lot of time wandering and reading there feeling incredibly lucky for having such generous access to books. Then, when I moved to New Hampshire, I encountered the Louis Kahn library at Phillips Exeter Academy. In the four years I studied at Exeter, this building never ceased to overwhelm me with its aesthetic power. Flipping through books in that library felt like a spiritually important task, and while I didn’t know it was awe that I was experiencing, I certainly realized that the Xidan Books Building was only a building of books and nothing more. Naive as I was, when I came to Princeton, New Jersey, last fall, I realized on the first day the true weight of the privilege of studying in a Kahn library. When my new classmates exclaimed in awe of the size and beauty of the Firestone library or the Lewis Library designed by Frank Gehry, my mind traveled back to when I wrote papers by the wooden oval table at the bottom of the atrium in the Kahn library, light pouring in from high above. My experience with these libraries started me wondering: how could we design more spaces that lift our spirits, just like Kahn’s Exeter library did?

In this essay, I will write about incorporating awe into architectural design, through the lens of positive psychology and cognitive neuroscience. This past summer, I went to the University of Pennsylvania to research on how the emotion of awe could inform spatial design. As a visiting student at the Positive Psychology Center, I read aesthetics, architectural theory and psychology with scientist David Yaden, who investigates awe and other self-transcendent experiences. I also sat in weekly lab meetings at the Center for Neuroaesthetics to learn more about the neuroscience of the topic.

An important philosophical distinction to make first, is between the sublime and the merely beautiful. This distinction is a comparison almost every philosopher of aesthetics makes. The common distinguishing feature is the amount of challenge present in the aesthetic experience. While the beautiful is pleasing (often catered to be so), the aesthetic sublime presents a degree of challenge to our sense-making process and demands effort on our own end to adjust mentally to. As Kant put it, experiences of the sublime “contravene the ends of our power of judgement, to be ill-adapted to our faculty of presentation, and to do violence, as it were, to the imagination.”1 This means that, while looking at neuroscientific findings on visual or spatial features that are pleasing and preferred in the studies, certain mitigation from the designer is necessary to provide challenging cues that make the designed space more than simply “beautiful.”

From the perspective of psychology, the sublime is usually referred to as “awe.”2 Awe is an emotional response to perceptually vast stimuli that challenge a person’s original conceptual framework3. Awe can accompany not only religious and aesthetic experiences, but also in scientific inquiry4. When a person experiences awe, he or she experiences a diminished self — he or she is now part of something larger than oneself. The prototypical experience of awe is astronauts looking at the Earth in the space: termed “the Overview Effect,” astronauts often report an increased sense of connection to humanity and the Earth as a whole and want to engage in protecting the environment afterwards5. Awe can result in feelings of self-diminishment and enhanced feelings of connection with other people and one’s environment6. Research has also shown that awe is capable of prompting prosocial and altruistic behaviors, and enhances life satisfaction7.

Neuroscientists researching awe have shown that it is associated with reduced activity in the Default Mode Network of the brain, which usually means a reduced engagement with self-reflective thoughts and greater attunement to the present moment8. Dominance of the DMN activity, it has shown, is associated with higher levels of maladaptive, depressive rumination, which is a core component of major depression disorder9. These converging lines of evidence suggest the possibility that frequent contacts with awe could enhance one’s mental well-being.

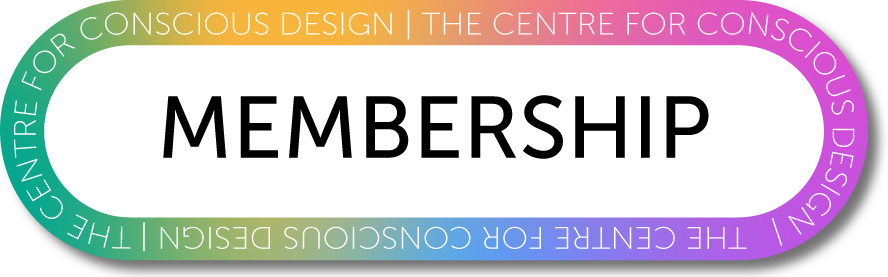

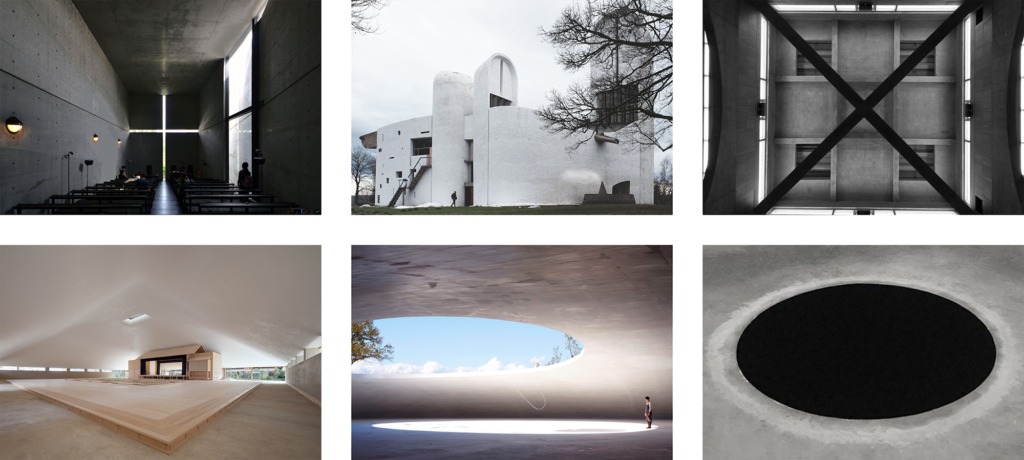

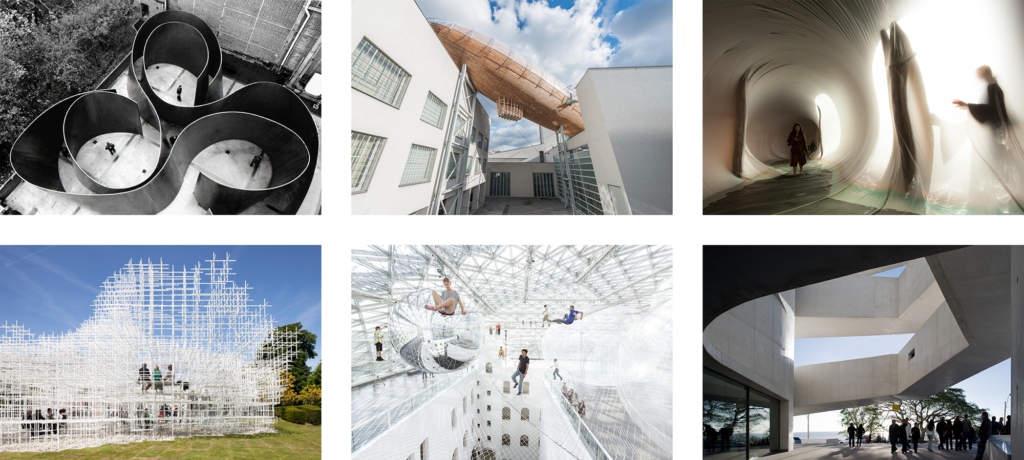

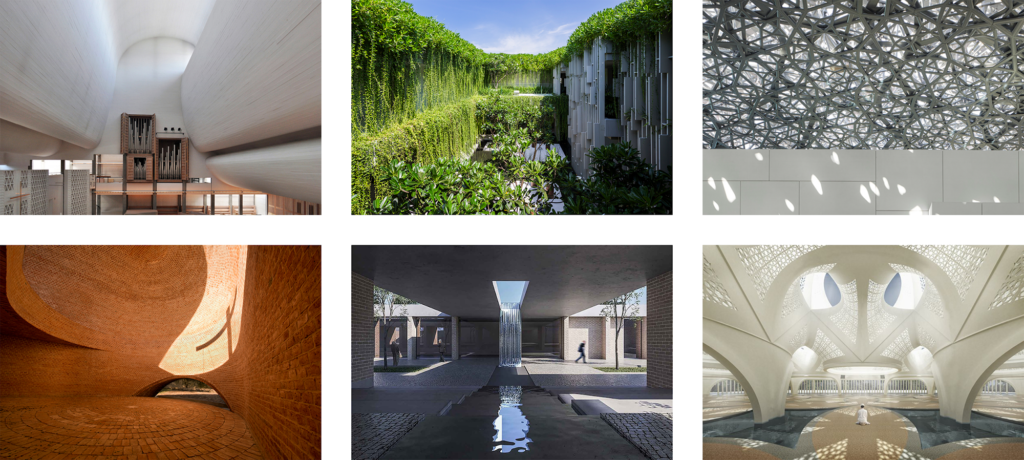

From the background information on awe from philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience, I developed five general principles for introducing awe-inspiring factors into design. Each design principle is defined, accompanied by a visual example, complemented with an idea from aesthetics theories, and supported with research findings from psychology and neuroscience. My aim is to provide practical design suggestions by drawing on the philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience of awe and the sublime.

1. Infinity

Infinity involves mainly two components: magnitude and repetition. From magnitude and repetition derives the totality that characterizes the magnitude of encounters with the sublime.

Magnitude may be further divided into the subgroups of physical and conceptual magnitude. With physical magnitude, there are magnitudes in scale or in material. A magnitude in scale could be measured in the height and width of a space or structure. A magnitude in material lies in the weight or implied weight of the material used in the structure. Conceptual magnitude is the infinite quality of knowledge, often on matters of time and cosmic relations beyond our thinking or imagination. I will mainly discuss physical magnitude here as conceptual magnitude relies more on symbols and settings.

Examples of infinity through magnitude include an open space, a tall structure, heavy material, or extremely light material. An open space is intuitively more conducive to producing sublime experiences, as the human body recognizes its relative small scale in comparison to the vast space. Perceived spatial magnitude could be created through both vertical and horizontal expansion. Materials that are or appear heavy like concrete, cement and bricks, as well as materials or structures that appear very light, could be helpful in producing the perception of magnitude.

In the book dedicated to investigating the sublime and the beautiful, philosopher Edmund Burke listed “vastness” and “infinity” as two of the factors in his topology of the sublime10. On physical magnitude, he particularly mentioned that vertical magnitude is more impactful than horizontal magnitude on perception of spaciousness. In addition to physical magnitude, Burke made the point that vastness and sublime could also be found in smallness, because smallness, when it is pushed to an extreme, can demonstrate the infinite complexity of the microscopic as well as the macroscopic. There are two ends of infinity, and the sublime is about pursuing extremes.

In terms of psychological research, the principle of infinity maps onto perceived vastness, which, together with the need for accommodation, constitute the prototypical awe, according to the seminal paper by Dacher Keltner and Jonathan Haidt11. From the perspective of neuroscience, there have been many studies on spaciousness and its components. An fMRI study found that participants judged open rooms as more beautiful and open interiors activated in the temporal lobes that contributes to the temporal dynamics of visual processing12.

Vast open spaces are often a preferred environmental trait, so we can look at specific elements contributing to the perception of openness. Researcher and architect, Arthur E. Stamps III, discovered, through several rounds of experiments, that horizontal area is the most effective in producing the perception of spaciousness, followed by height13. Spaces with high ceilings are also more likely to be judged beautiful than with low ceilings14. Several other factors contribute to perception of spaciousness as well. Ceilings with brighter colors are perceived more spacious than darker colors, while the hue and saturation of the ceiling color have no effect on spaciousness perception15. Fractal rooms with rough walls were judged to be more spacious than smooth walls16. Locomotive permeability–the size of the area over which one could walk on–also highly influences perceived spaciousness, more than visual permeability17.

However, going back to the distinction between the sublime and the beautiful, the link between perceived spaciousness and awe is not straightforward. While height hasn’t been shown to be particularly effective in producing spaciousness, it has been hypothesized by psychologists to be a major elicitor of awe. One psychology study did reveal that simply exposing individuals with pictures of tall buildings triggers behavioral freezing, which is a state to which awe has been linked to18.

Repetition, the second component of infinity, is the multiplication of uniformly shaped objects in single directions. Burke gives a great intuition-based explanation: processing the uniform repetition of an object in one direction gives the brain the gradual ease in not having to re-recognize every new object, and tricks the mind into the false perception of infinity19.

In psychology, repetition has been addressed as a part of grouping, a fundamental Gestalt principle. Alternating columns in architecture provides an example occasion for grouping, which is a way for our visual system to order repeated and statistically correlated information together20. The aesthetic experience of viewing ordered patterns in architecture may be mitigated by the synchronized action potentials among associated neurons that are triggered by the grouped features21.

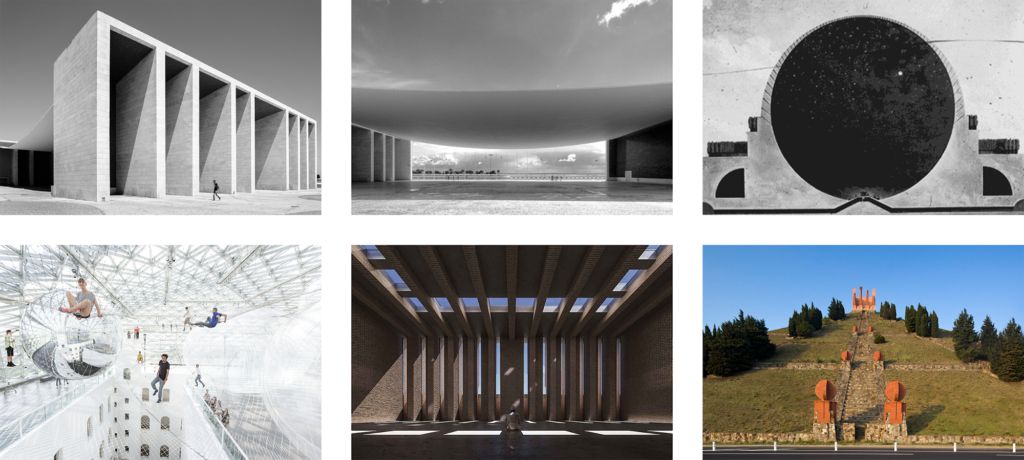

An example of artful incorporation of visual and conceptual infinity into architectural design, is Emilio Ambasz’s Cordoba House. Two sets of thin, metal stairs stretch out in single directions alongside two tall, rough, white walls forming a right angle, leading one from the ground to the balcony and back. As one walks up or down what could appear to be infinitely unfolding stairs, he or she is always reminded of the sheer weightlessness and small size of his or her body against the massive stuccoed walls. The sunlight reflects off the white walls, its brightness slightly interfering with one’s vision.

Totality is the effect that infinity should achieve. It is an overwhelming immersion of sensory input. Totality has always accompanied philosophers’ distinction of the sublime from the beautiful. To Kant, whereas the beautiful consists in limitation, the sublime represents limitlessness with an added totality. Instead of being a separate topological element of the sublime, totality refers to the scale of the effect achieved by infinity22. The perceptual or conceptual infinity has to harness enough power to make itself immersive.

While the term of totality is not specifically identified in psychology of awe, the concept of it lies at the basis of awe’s definition. The need for accommodation in Keltner and Haidt’s paper requires the degree of perceived vastness to reach to such a point where it becomes so immersive that one’s mental structures have to be adjusted to assimilate the new experience.

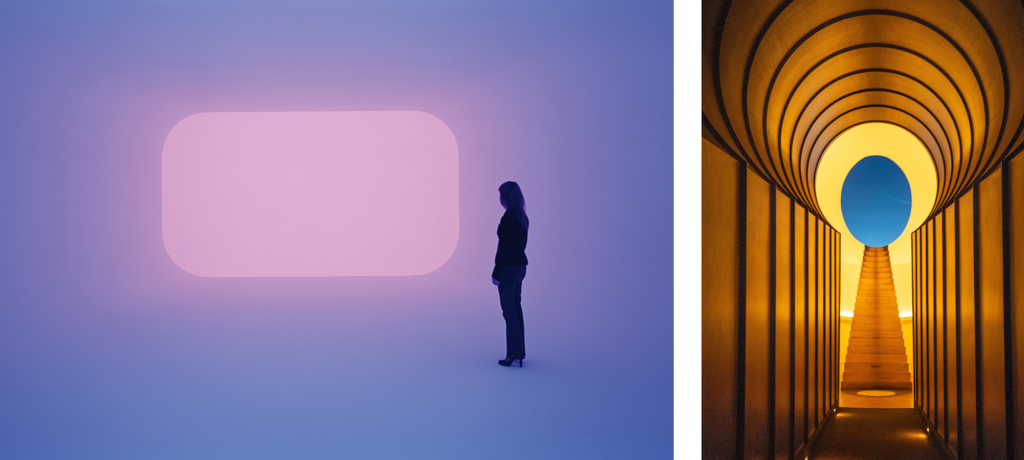

A great example of totality is achieved through James Turrell’s art. In his light installations, Turrell incorporates the Ganzfeld effect, which is when everything in the visual input shares the same color and brightness23. When we experience the Ganzfeld effect, our brain struggles to detect depth and our visual system shuts down due to “sensory deprivation.” This catches us off guard and makes us confront the wordless internal realm that sets up for sublime experiences.

If the contact with awe has a rhythm, it is a pause. If it has a sound, it is silence.

It is hard to pinpoint what silence in awe-infused design is. It is not a specific element, but an artful combination of elements. Some architects whose awe-inspiring works have been described as “silent” include Etienne Louis Boulée, Louis Kahn, and Tadao Ando. As diverse as the backgrounds they came from and as rich as their design methodologies are, a commonality amongst their design is a dramatic choreography of light and shadow. This feature corresponds philosophically with the pursuit of extremes in sublime experiences that I mentioned in the first section of infinity. Bringing extremely contrasting lighting conditions together emphasizes a fundamental quality of the sublime: pursuing the extremes.

Philosophers and writers speak of awe experiences with the quality of “static” and “motionless.” In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce wrote: “The esthetic emotion…is static. The mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing”33. Burke focused on the suddenness–“a sudden beginning or sudden cessation of a sound”–and low intermittent sound34. These qualities of sound Burke described share the unexpectedness and the feeling of suspension (due to momentum) that silence here characterizes. Silence could be seen as a self-perception of the need for accommodation, marking one of the two features of awe.

In psychology and neuroscience, awe has always been associated with an immobilizing quality. Several papers have linked awe with “freezing,” “stillness,” “passivity,” and “immobility”35. A 2016 research showed participants images of tall buildings to elicit some degree of awe and participants demonstrated temporary behavioral freezing with more bodily immobility and slower response time in a brief moment36. This counterproductive reaction towards potentially awe-inspiring spaces suggests that awe alone is not always necessarily desired for design. However, tall buildings and installment of tall trees have been proven to be beneficial in other ways, such as reducing burglary rate37.

The association between “silence” and awe could come from a different perspective: solitude and reflection. Burke wrote: “All general privations are great, because they are all terrible; Vacuity, Darkness, Solitude and Silence.”38 While Burke’s sublime had a more negative association than the awe I am discussing here, and while it is important to remember that sublime has the power to negatively influence its spectators, Burke nonetheless is touching on something important here: some mitigations of private or semi-private spaces in an awe-inducing space.

In fact, psychologists Michelle Shiota, Dacher Keltner and Amanda Mossman, in a paper on the elicitors of awe, suggested that awe should be less of a social emotion than happiness, as it should be elicited by “perceptually or conceptually complex, information-rich stimuli.”39 Here we see once again the important and inherent difference between an awe-inspiring experience and a pleasant experience, regarding their social and complexity qualities, that designers should remember in choosing when to include awe-oriented design features.

There are a few specific design features that could be considered in giving silence to a space: small windows or openings, dramatic choreography of light and shadow, half-enclosed spaces, and relatively neutral colors. Colors like bright yellow or red would easily do the opposite of creating the privateness of silence.

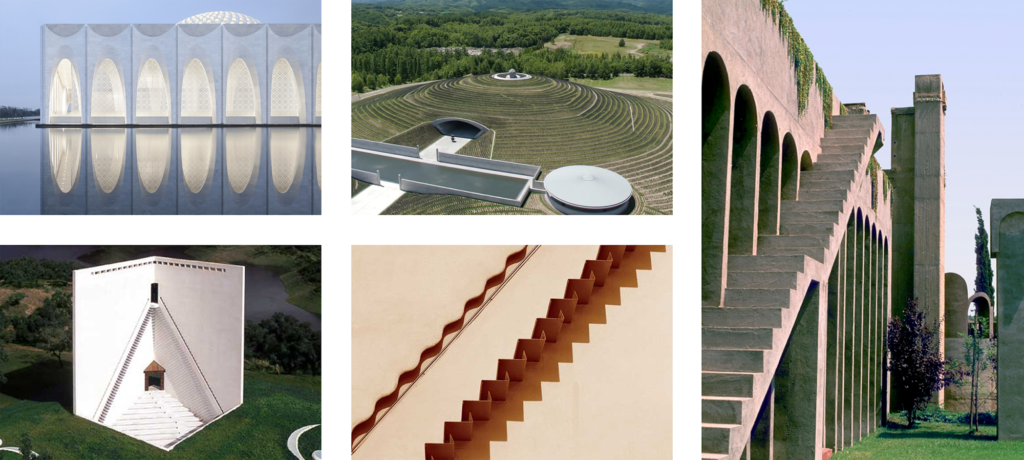

Safe threat is the presence of a threat with a reliable safeguard. Being a broad concept, it could manifest visually as having obscured visual clues.

This is perhaps the hardest principle to explain out of all five. Why would we want to inflict any sense of threat in a space that is supposed to generate a positive, spiritual emotion? Safe threat makes for a crucial distinction between the sublime and the beautiful. Burke, along with many philosophers in history, wrote that an essential character of the sublime is that it has the power to hurt yet does not care to hurt40. Whenever a power or strength is employable for our own pleasure or benefit, it becomes anything but sublime. Building on Burke, Kant made it clearer that we judge it all the more sublime when we perceive danger but are in a secured position, because the sublime scenes “raise the forces of the soul above the height of vulgar commonplace, and discover within us a power of resistance of quite another kind.”41 Sublime is all about the power that brings us to an awareness of our own limits, through conceptual or physical power. And we often find joy in that, as this awareness of limits pushes us to be more alive.

Haidt and Keltner took Burke’s reasoning into their discussion on the different “flavours” of awe: threat is one of the five additional themes of awe, in addition to the two major features of vastness and accommodation42. In their table outlining how awe or awe-related states are “flavoured,” threat is marked as sometimes present in encounter with God.

Applying to the design practice for a spiritually elevating experience, the safe perception of threat could translate to the idea of mystery. Mysterious elements like a winding path or an obscured area — going back to the second element of obscurity — would encourage engagement43. Several studies on biophilic design, which I will talk about in the next section, mention “mystery”–the promise of more information–as one of the factors to increase preference for the environment44. A report by Terrapin Bright Green also listed “risk”– a perceived threat with safeguard–as one of their 14 biophillic design elements45.

For specific design elements, apart from winding paths and obscured areas, building structures deceivingly light or unstable, suspending an occupiable space, having a visually heavy structure looming over, and adding glass floors are also some direct features in increasing perceived safe risk of a space.

Perhaps the most well-known application of neuroscience to architecture is the incorporation of nature in therapeutic environments. Nature here broadly refers to the intentional introduction of materials or patterns to refer to nature.

There are two major forms of the nature element: extraction of natural materials and incorporation of biophilic forms and patterns. An example of extraction is a fountain, and there are many creative and unique ways to incorporate water as or than a fountain. Artworks by Olafur Eliasson, as well as Anish Kapoor’s Descension, could serve as inspirations, to name just a few examples from contemporary art. Incorporation of biophilic forms and patterns could be introducing curved walls and fractal patterns.

In aesthetics, nature has always been the more dominant subject in the topic of awe. Kant specifically mentioned at the start of his analysis of the sublime that “pure” aesthetic judgment would only be found in raw nature “merely as involving magnitude” because it does not involve the idea of purpose: all animals, for example, are excluded here because they invoke the concept of a natural order46.

Many neuroscience and psychology research support the above claims. A recent study shows that naturalistic patterns in architecture are, on average, preferred over synthetic patterns47. Another study concludes that natural aesthetic is more strongly shared among individuals than artifacts, which means that it is easier to elicit a shared aesthetic experience through nature than artificial elements48. Nature is also listed as the single most efficient factor in eliciting awe, towering art, other people’s accomplishments, social interaction and personal achievement49.

Before biophilic design, I want to first talk about the Attention Restoration Theory (ART), which complements the biophilia theory. Termed by Stephen Kaplan in his seminal 1995 paper, ART claims that we process most natural environments through bottom-up attention mechanisms, as opposed to top-down. A 2015 research based on ART found three low-level visual features that significantly predict the perception of naturalness: non-straight surfaces, borders, and shades, lower hue level (more yellow-green content over blue-purple content), and higher diversity in saturation50.

The biophilia hypothesis, coming from a more holistic perspective, was proposed by E. O. Wilson, and states that our sensory systems are highly sensitive to stimuli of the living or life-like forms in nature51. Biomorphic features have thus been hypothesized to be preferred aesthetically. A 2019 paper suggests that curvilinear surfaces are preferred over rectilinear surfaces for both architecture experts and nonexperts52. Fractals, another common biomorphic element, have been shown to be universally aesthetic, no matter if they are produced through natural processes, mathematics, or the human hand53. More specifically, fractal light patterns of medium to medium-high complexity are a lot more preferred aesthetically than other patterns54.

Regarding extraction of natural elements, I haven’t found many convincing studies that investigated in particular the health or well-being benefits of incorporating specific natural elements. However, a 2014 report that claims to have covered over 500 publications on biophilic responses on their research, did list “presence of water (design condition that allows seeing, hearing, or touching water),” “dynamic and diffuse light (light and shadow of varied intensities mimicking nature),” and “material connection with nature (material and natural elements with minimal processing),” as part of their 14 identified biophilic design elements55.

To complicate the topic of this paper, various holistic terms play a key role in aesthetic judgment and they cannot be reduced to specific elements of a formula. Research has shown a u-shaped relationship between complexity in spatial design and preference for the environment56. The notion of fluency comes in: researchers have been hypothesizing that humans prefer configurations that, while having some level of complexity, are also processed easily or fluently57. The ease of navigation in fluency could come from features like contrast, grouping, and symmetry58. Each of these features has its own complex rules and applications, so determining where the sweet spot is between complexity and preference is hugely dependent on the designers.

In the end, the sublime is about “some modification of power.”59 Many architectures across the world were designed to inspire the intimidating kind of awe for demonstration of political power. How can we play with that power of the sublime and let it heal and inspire? That is the ultimate question that perhaps could only be answered on an individual basis for each design project.

The goal of my research was not to say that we need to make all spaces as awe-inspiring as possible. I believe that we should situate architecture in its experiential nature, and I want to suggest that we can expand the idea of “awe” into a more secular setting for architectural design. Inspiring more connectedness–a component of self-transcendent emotions like awe–in individuals extends its power externally, as individuals may be more inclined to attribute social qualities to their spatial environment, and endorse beliefs in good nature of the world60. It is an important concept to be taken care of in the design process and it can only be done so seriously when we take awe out of the traditional religious associations. Introducing awe and inspiring more connectedness in public spaces as well as domestic environments is too complicated for a short article like mine to tackle. Not a lot of cognitive neuroscience research directly addresses this topic, and I hope my article can bring more awareness to this design question, for designers and researchers alike.

Visual supplement of the paper: https://www.notion.so/Awe-inspiring-spatial-design-with-examples-from-art-and-architecture-6acf86e62af94fa0a5c5f7ad4dfc105a

References

1 I. Kant, Critique of judgement, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 76. (Original work published 1790)

2 R. R. Clewis, The Sublime Reader, 2019. Available from: Kindle, (accessed 3 August 2019).

3 D. Keltner and J. Haidt, ‘Approaching awe , a moral , spiritual , and aesthetic emotion’, Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 2003, 297–314, https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930244000318.

4 S. Gottlieb, D. Keltner and T. Lombrozo, ‘Awe as a Scientific Emotion’, Cognitive Science, 42(6), 2018, 2081–2094, https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12648.

5 D. B. Yaden et al., ‘The overview effect: Awe and self-transcendent experience in space flight’, Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3(1), 2016, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000086.

6 D. B. Yaden et al., ‘The varieties of self-transcendent experience’, Review of General Psychology, 21(2), 2017, 143-160; D. B. Yaden et al., ‘The development of the Awe Experience Scale (AWE-S): A multifactorial measure for a complex emotion’, The journal of positive psychology, 14(4), 2019, 474-488.

7 P. K. Piff et al., ‘Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 2015, 883–899, https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000018.; M. Rudd, K. D. Vohs and J. Aaker, ‘Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being’, Psychological Science, 23(10), 2012, 1130–1136, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612438731.

8 M. van Elk et al., ‘The neural correlates of the awe experience: Reduced default mode network activity during feelings of awe’, Human Brain Mapping, (April), 2019, 3561–3574, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24616.

9 J. P. Hamilton et al., ‘Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: Implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination’, Biological Psychiatry, 70(4), 2011, 327–333, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003.

10 E. Burke, A philosophical enquiry into the sublime and the beautiful, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 59-60. (Original work published 1757)

11 Keltner and Haidt, ‘Approaching awe’.

12 O. Vartanian et al., “Architectural design and the brain: Effects of ceiling height and perceived enclosure on beauty judgments and approach-avoidance decisions”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 2015, 10–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVP.2014.11.006.

13 A. E. Stamps, “Effects of Area, Height, Elongation, and Color on Perceived Spaciousness”, Environment and Behavior, 43(2), 2011, 252–273, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509354696.; A. E. Stamps, “On Shape and Spaciousness. Environment and Behavior”, 41, 2009, 526–548, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508317931.

14 Vartanian et al., “Architectural design and the brain”.

15 C. von Castell, H. Hecht and D. Oberfeld, “Which Attribute of Ceiling Color Influences Perceived Room Height?” Human Factors, 60(8), 2018, 1228–1240, https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720818789524.

16 A. E. Stamps and V. V. Krishnan, “Spaciousness and boundary roughness”, Environment and Behavior, 38(6), 2006, 841–872, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506288052.

17 A. E. Stamps, “Effects of Multiple Boundaries on Perceived Spaciousness and Enclosure”, Environment and Behavior, 45(7), 2013, 851–875, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512446808.

18 Y. Joye and S. Dewitte, “Up speeds you down. Awe-evoking monumental buildings trigger behavioral and perceived freezing”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 47, 2016, 112–125.

19 Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry, p. 61.

20 C. Alexander, The phenomenon of life: An essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe, Berkeley, CA: Center for Environmental Structure, 2002.

21 V. Ramachandran and W. Hirstein, ‘The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, (6), 1999, 16–51, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528139208953747; Alexander.

22 Kant, Critique of Judgment.

23 E. Kandel, Reductionism in Art and Brain Science: Bridging the Two Cultures, New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2016.

24 Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry, p. 48.

25 M. Mendelssohn, ‘On the sublime and naive in the fine sciences’, in R. Clewis (ed.), The Sublime Reader [Kindle Edition], 2019. (Reprinted from Philosophical writings, edited by D. Dahlstrom, 1997, Cambridge University Press).

26 Keltner and Haidt, ‘Approaching awe’.

27 Kandel, Reductionism in Art and Brain Science.

28 C. D. Gilbert and W. Li, ‘Top-down influences on visual processing’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(5), 2013, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3476.

29 A. Mechelli et al., ‘Where bottom-up meets top-down: Neuronal interactions during perception and imagery’, Cerebral Cortex, 14(11), 2004, 1256–1265, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhh087.

30 T. D. Albright, Perceiving. Daedalus, 144(1), 2015, 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00315.

31 Kandel, Reductionism in Art and Brain Science.

32 J. Turrell, Introduction, retrieved from http://jamesturrell.com/about/introduction/.

33 J. Joyce, A portrait of the artist as a young man, New York: The Viking Press, 1964.

34 Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry, pp. 68-69.

35 V. Griskevicius, M. N. Shiota and S. L. Neufeld, ‘Influence of Different Positive Emotions on Persuasion Processing: A Functional Evolutionary Approach’, Emotion, 10(2), 2010, 190–206, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018421.; J. Haidt and D. Keltner, ‘Awe/responsiveness to beauty and excellence’, in C. Peterson & M.E.P. Seligman (Eds.), The VIA taxonomy of strengths, Cincinnati, OH: Valves in Action Institute, 2002.; M. N. Shiota et al., ‘Feeling Good: Autonomic Nervous System Responding in Five Positive Emotions’, Emotion, 11(6), 2011, 1368–1378, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024278.

36 Y. Joye and S. Dewitte, ‘Up speeds you down. Awe-evoking monumental buildings trigger behavioral and perceived freezing’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 47, 2016, 112–125.

37 D. Chang, ‘Social crime or spatial crime? exploring the effects of social, economical, and spatial factors on burglary rates’, Environment and Behavior, 43(1), 2011, 26–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509347728; G. H. Donovan and J. P. Prestemon, ‘The effect of trees on crime in Portland, Oregon’, Environment and Behavior, 44(1), 2012, 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510383238.

38 Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry, pp. 53-54.

39 M. N. Shiota, D. Keltner and A. Mossman, ‘The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept’, Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 2007, 944–963, https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600923668.

40 Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry, p. 54.

41 Kant, Critique of Judgment, p. 91.

42 Keltner and Haidt, ‘Approaching awe’.

43 S. Kaplan, ‘Environmental preference in a knowledge-seeking, knowledge-using organism’, in J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (eds.), The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture, New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

44 M. S. Abdelaal and V. Soebarto, ‘Biophilia and Salutogenesis as restorative design approaches in healthcare architecture Biophilia and Salutogenesis as restorative design approaches in healthcare architecture’, ARCHITECTURAL SCIENCE REVIEW, 62(3), 2019, 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/00038628.2019.1604313.; J. L. Nasar and E. Cubukcu, ‘Evaluative appraisals of environmental mystery and surprise’, Environment and Behavior, 43(3), 2011, 387–414, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510364500.

45 W. Browning, C. Ryan and J. Clancy, 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health & Well-being in the Built Environment, 2014, retrieved from https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/14-Patterns-of-Biophilic-Design-Terrapin-2014p.pdf

46 Kant, Critique of Judgment, pp. 83-84.

47 A. Coburn et al., ‘Psychological responses to natural patterns in architecture’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 62(February), 2019, 133–145, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.02.007.

48 E. A. Vessel et al., ‘Stronger shared taste for natural aesthetic domains than for artifacts of human culture’, Cognition, 179, 2018, 121–131, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COGNITION.2018.06.009.

49 Shiota, Keltner and Mossman, ‘The nature of awe’.

50 O. Kardan et al., ‘Is the preference of natural versus man-made scenes driven by bottom-up processing of the visual features of nature?’ Frontiers in Psychology, 6(APR), 2015, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00471.

51 E. O. Wilson, Biophilia, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

52 O. Vartanian, ‘Preference for curvilinear contour in interior architectural spaces: Evidence from experts and nonexperts’, Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 13(1), 2019, 110–116, https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000150.

53 B. Spehar et al., ‘Universal aesthetic of fractals. Computers & Graphics’, 27, 2003, 813–820, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0097-8493(03)00154-7.

54 B. Abboushi et al., ‘Fractals in architecture: The visual interest, preference, and mood response to projected fractal light patterns in interior spaces’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 61(December 2017), 2019, 57–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.12.005.

55 Browning, Ryan and Clancy, 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design.

56 Ç. Imamoglu, “Complexity, liking and familiarity: Architecture and non-architecture Turkish students’ assessments of traditional and modern house facades”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 20(1), 2000, 5–16, https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1999.0155.

57 N. Schwarz, P. Winkielman and R. Reber, “Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure : Is Beauty in the Perceiver’s Processing Experience?” Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(4), 2004, 364–382.

58 V. Ramachandran and W. Hirstein, ‘The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, (6), 1999, 16–51, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528139208953747.

59 Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry, p. 53.

60 Yaden et al., ‘The varieties of self-transcendent experience’.

Reference List

Abboushi, B. et al.. ‘Fractals in architecture: The visual interest, preference, and mood response to projected fractal light patterns in interior spaces’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 61(December 2017), 57–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.12.005.

Abdelaal, M. S. and Soebarto, V. ‘Biophilia and Salutogenesis as restorative design approaches in healthcare architecture Biophilia and Salutogenesis as restorative design approaches in healthcare architecture’. ARCHITECTURAL SCIENCE REVIEW, 62(3), 2019, 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/00038628.2019.1604313.

Albright, T. D. Perceiving. Daedalus, 144(1), 2015, 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00315.

Alexander, C. The phenomenon of life: An essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe. Berkeley, CA: Center for Environmental Structure, 2002.

Browning, W., Ryan, C. and Clancy, J. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health & Well-being in the Built Environment, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/14-Patterns-of-Biophilic-Design-Terrapin-2014p.pdf

Burke, E. A philosophical enquiry into the sublime and the beautiful. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015 (Original work published 1757)

Chang, D. ‘Social crime or spatial crime? exploring the effects of social, economical, and spatial factors on burglary rates’. Environment and Behavior, 43(1), 2011, 26–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509347728.

Clewis, R. R., The Sublime Reader, 2019. Available from: Kindle, (accessed 3 August 2019).

Coburn, A. et al., ‘Psychological responses to natural patterns in architecture’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 62(February), 2019, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.02.007.

Donovan, G. H. and Prestemon, J. P. ‘The effect of trees on crime in Portland, Oregon’. Environment and Behavior, 44(1), 2012, 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510383238.

Gilbert, C. D. and Li, W. ‘Top-down influences on visual processing’. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(5), 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3476.

Gottlieb, S., Keltner, D. and Lombrozo, T. ‘Awe as a Scientific Emotion’. Cognitive Science, 42(6), 2018, 2081–2094. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12648.

Griskevicius, V., Shiota, M. N. and Neufeld, S. L. ‘Influence of Different Positive Emotions on Persuasion Processing: A Functional Evolutionary Approach’. Emotion, 10(2), 2010, 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018421.

Haidt, J. and Keltner, D. ‘Awe/responsiveness to beauty and excellence’. In C. Peterson & M.E.P. Seligman (Eds.), The VIA taxonomy of strengths. Cincinnati, OH: Valves in Action Institute, 2002.

Hamilton, J. P et al.. ‘Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: Implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination’. Biological Psychiatry, 70(4), 2011, 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003.

Imamoglu, Ç. ‘Complexity, liking and familiarity: Architecture and non-architecture Turkish students’ assessments of traditional and modern house facades’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 20(1), 2000, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1999.0155.

Joyce, J. A portrait of the artist as a young man. New York: The Viking Press, 1964.

Joye, Y. and Dewitte, S. ‘Up speeds you down. Awe-evoking monumental buildings trigger behavioral and perceived freezing’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 47, 2016, 112–125.

Kandel, E. Reductionism in Art and Brain Science: Bridging the Two Cultures. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Kant, I. Critique of judgement. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007 (Original work published 1790)

Kaplan, S. ‘Environmental preference in a knowledge-seeking, knowledge-using organism’. In J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Kaplan, S. ‘The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 1995, 169–182.

Kardan, O. et al., ‘Is the preference of natural versus man-made scenes driven by bottom-up processing of the visual features of nature?’ Frontiers in Psychology, 6(APR), 2015, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00471.

Keltner, D. and Haidt, J. ‘Approaching awe , a moral , spiritual , and aesthetic emotion’. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 2003, 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930244000318.

Mechelli, A. et al. ‘Where bottom-up meets top-down: Neuronal interactions during perception and imagery’. Cerebral Cortex, 14(11), 2004, 1256–1265. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhh087.

Mendelssohn, M. ‘On the sublime and naive in the fine sciences’. In R. Clewis (Ed.), The Sublime Reader [Kindle Edition], 2019. (Reprinted from Philosophical writings, edited by D. Dahlstrom, 1997, Cambridge University Press).

Nasar, J. L. and Cubukcu, E. ‘Evaluative appraisals of environmental mystery and surprise’. Environment and Behavior, 43(3), 2011, 387–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510364500.

Piff, P. K. et al. ‘Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 2015, 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000018.

Ramachandran, V. and Hirstein, W. ‘The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience’. Journal of Consciousness Studies, (6), 1999, 16–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528139208953747.

Rudd, M., Vohs, K. D. and Aaker, J. ‘Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being’. Psychological Science, 23(10), 2012, 1130–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612438731.

Schwarz, N., Winkielman, P. and Reber, R. “Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure : Is Beauty in the Perceiver ’ s Processing Experience ?” Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(4), 2004, 364–382.

Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D. and Mossman, A. ‘The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept’. Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 2007, 944–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600923668.

Shiota, M. N. et al. ‘Feeling Good: Autonomic Nervous System Responding in Five Positive Emotions’. Emotion, 11(6), 2011, 1368–1378. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024278.

Spehar, B. et al. ‘Universal aesthetic of fractals’. Computers & Graphics, 27, 2003, 813–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0097-8493(03)00154-7.

Stamps III, A. E. ‘On Shape and Spaciousness’. Environment and Behavior, 41, 2009, 526–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508317931

Stamps, A. E. ‘Effects of Area, Height, Elongation, and Color on Perceived Spaciousness’. Environment and Behavior, 43(2), 2011, 252–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509354696.

Stamps, A. E. ‘Effects of Multiple Boundaries on Perceived Spaciousness and Enclosure’. Environment and Behavior, 45(7), 2013, 851–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512446808.

Stamps, A. E. and Krishnan, V. V. ‘Spaciousness and boundary roughness’. Environment and Behavior, 38(6), 2006, 841–872. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506288052.

Turrell, J. Introduction. Retrieved from http://jamesturrell.com/about/introduction/.

van Elk, M. et al. ‘The neural correlates of the awe experience: Reduced default mode network activity during feelings of awe’. Human Brain Mapping, (April), 2019, 3561–3574. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24616.

Vartanian, O. et al. ‘Architectural design and the brain: Effects of ceiling height and perceived enclosure on beauty judgments and approach-avoidance decisions’. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 2015, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVP.2014.11.006.

Vartanian, O. et al. ‘Preference for curvilinear contour in interior architectural spaces: Evidence from experts and nonexperts’. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 13(1), 2019, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000150.

Vessel, E. A. et al. ‘Stronger shared taste for natural aesthetic domains than for artifacts of human culture’. Cognition, 179, 2018, 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COGNITION.2018.06.009.

von Castell, C., Hecht, H. and Oberfeld, D. ‘Which Attribute of Ceiling Color Influences Perceived Room Height?’ Human Factors, 60(8), 2018, 1228–1240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720818789524.

Wilson, E. O. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Yaden, D. B. et al. ‘The varieties of self-transcendent experience’. Review of General Psychology, 21(2), 2017, 143-160.

Yaden, D. B. et al. ‘The overview effect: Awe and self-transcendent experience in space flight’. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3(1), 2016, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000086.

Yaden, D. B. e al. ‘The development of the Awe Experience Scale (AWE-S): A multifactorial measure for a complex emotion’. The journal of positive psychology, 14(4), 2019, 474-488.