Abstract

The relationship between the environment and its occupants has been a scholarly debate since the late 13th century. Today, the environment—including cities, buildings, populations, and infrastructure —accommodates an astounding eight billion people1. These conditions significantly impact human performance and well-being, yet the methods to measure these effects still require improvement. This study reviews existing research on the mental health impacts of built environments, identifies gaps in current measurement methods, and proposes a framework for collecting and analysing data to explore the link between neighbourhood quality, social ambience, and residents’ mental health. Fundamental limitations include inadequate data availability, insufficient multidisciplinary integration in measurement tools or training, and the lack of standardised measurement criteria. The proposed framework employs a mixed-methodologies approach, combining observation visits, citizen surveys, psychological assessments, and real-time data collection. This method was tested in Bogotá, Colombia, across three distinct city areas, providing valuable insights into its effectiveness. Implementing these recommendations can improve the accuracy and relevance of future research, ultimately fostering healthier urban environments that better support mental well-being.

Introduction

Urban planners and architects typically concentrate on designing functional cities but often overlook the impact of these environments on people’s mental health.

The techniques used today to evaluate the environment’s impact on mental health include quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative methods involve surveys, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and environmental monitoring, while qualitative approaches include interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic studies. Mixed-method approaches, which combine these techniques, enhance data validity by allowing for data triangulation, thus strengthening the robustness of findings. However, mixed methods still have significant limitations. The lack of uniform measurement criteria, limited public access to psychological data (such as mental health statistics and individual assessments), time consumption, high costs and approach inconsistencies hinder comprehensive and comparable conclusions. Most methods focus on physical or social environmental factors in isolation rather than their complex interactions between the built environment, social dynamics, and psychological responses.

Besides, studies focus primarily on high-income, urban settings in the Global North, with limited research in the Global South and low-income regions. For example, of 99 papers published between 1995 and 2007 regarding the “evidence of the effect of the built and physical environment on mental health”, more than half of the studies were conducted in countries of the Global North. In contrast, there was a notable lack of research from the Global South and low-income regions, highlighting a significant gap in the geographical distribution of mental health research2. This bias results in a narrow understanding of how the built environment affects mental well-being across different cultural and socioeconomic contexts, leading to generalised policy recommendations. As such, there is a pressing need for more integrated, multidisciplinary approaches that combine objective measurements with subjective experiences, particularly in data-scarce contexts like developing countries.

To address these gaps, this case study introduces a comprehensive research method that integrates quantitative and qualitative variables, offering an efficient, adaptable, and cost-effective approach. By using free, accessible resources and streamlining the data collection and analysis process, researchers designed this method to be easily transferable to other settings. It also promotes collaboration by involving multidisciplinary professionals throughout the research process, ensuring diverse perspectives and a more holistic understanding of the relationship between the built environment and mental health. This approach increases efficiency and broadens the potential for real-world applications across various contexts.

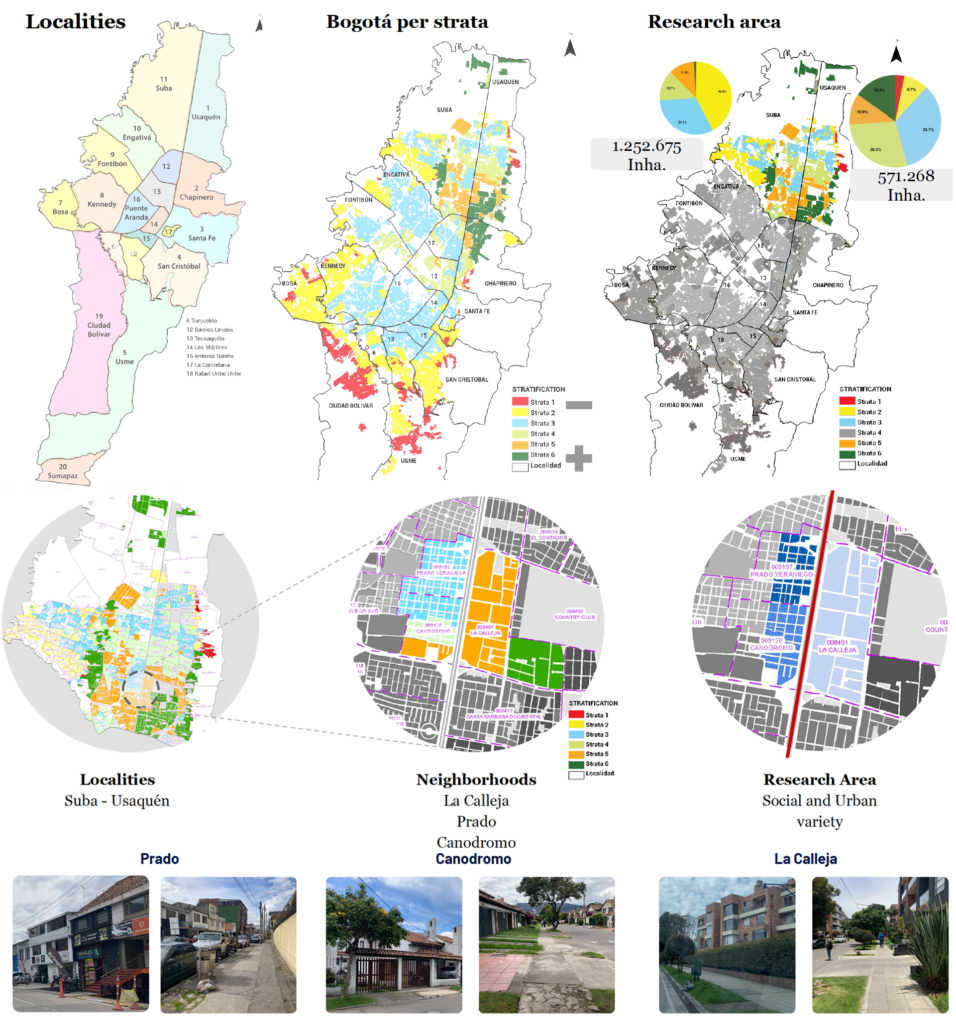

We tested our framework in Bogotá, Colombia, the second-most populous country in South America, with a population of 51,265,841 as of 2021, 80% of whom live in urban areas3. The study focused on three neighbourhoods in northern Bogotá—La Calleja, Canodromo, and Prado—selected based on their social strata, the presence of relevant variables, and a manageable size. These neighbourhoods represent a range of social classes, from middle-low to upper-middle, as classified by Bogotá’s residential property system for public utilities. This selection ensures a diverse and rich context while maintaining the operational feasibility of the study. By focusing on communities with standardised socio-economic conditions, the approach aims to minimise the influence of external factors, such as low-income or high-violence environments, that could skew mental health data. This methodology provided an ideal setting to pilot the framework and gather actionable insights for promoting healthier urban environments.

The Neighbourhood Health-Impact Assessment Framework: A Step-by-Step Approach

This study introduces the Neighbourhood Health-Impact Assessment Framework (NHIAF), a comprehensive tool designed to assess how the built environment correlates with mental health outcomes. The NHIAF follows six structured steps to ensure a detailed evaluation applicable across various urban settings.

- The initial step identifies the study context by establishing the general environment and specific conditions under study, including components and variables, emphasising neighbourhood quality, social capital, and mental health to be analysed.

- The research boundaries are defined based on socio-geographic parameters. Social strata determine the scope, influencing all study domains, including geographical subdivisions.

- The study area is then selected according to predefined criteria, focusing on scale and operational feasibility.

- An information check-in and cross-matching step verify and cross-references secondary data with existing information.

- Structured surveys are subsequently conducted, including the administration of psychological tests like the DASS-21 to evaluate the severity of mental disorders symptoms.

- Statistical analysis is performed to identify patterns and correlations through descriptive, correlation and regression methods.

This framework offers a structured yet flexible, time- and cost-effective approach for researchers and urban planners to analyse the relationship between the built environment and mental health. By leveraging free and publicly available data, the framework ensures that resources are used efficiently, even in resource-constrained environments. Its six-step process allows adaptability to different urban contexts while maintaining rigorous data collection and analysis standards.

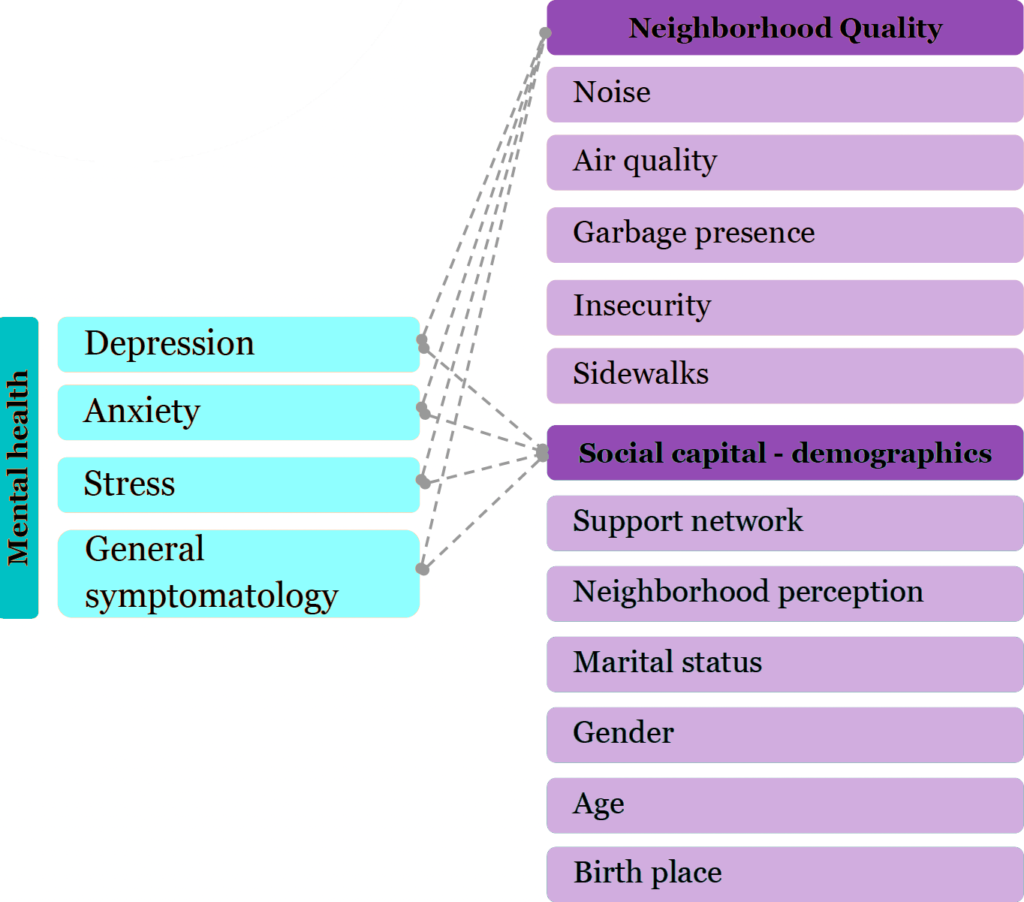

Our case study – methodology

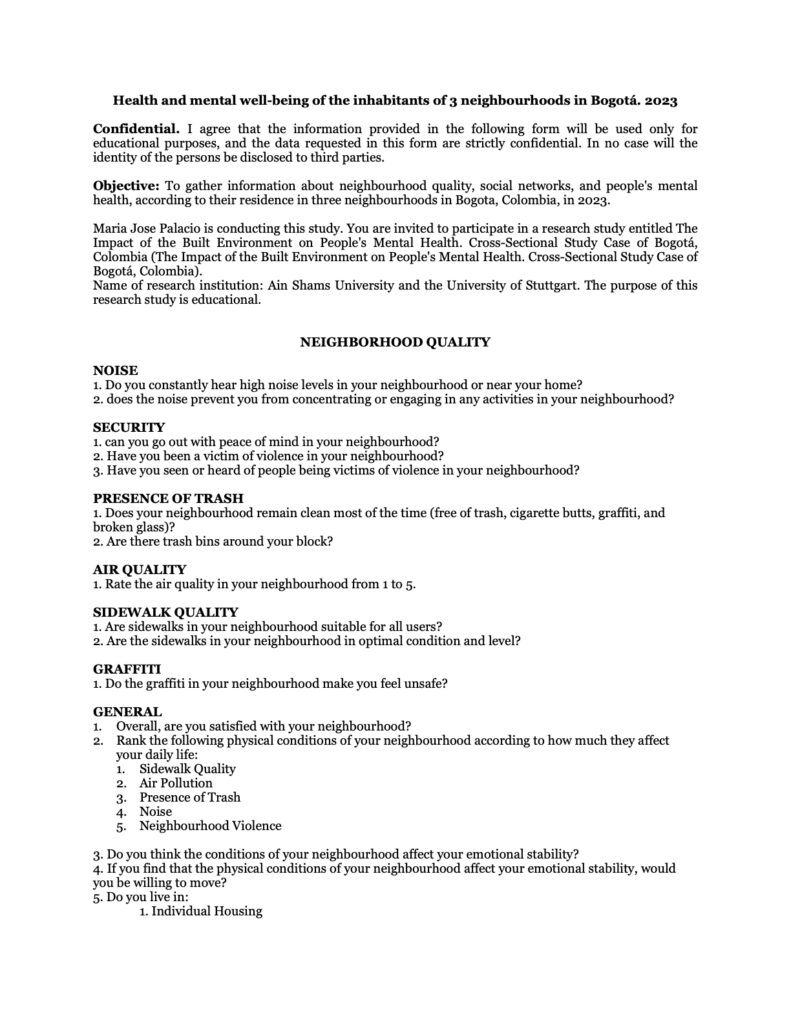

Key variables in this study include built environment determinants such as air quality, noise, insecurity, garbage presence, and sidewalk quality for neighbourhood conditions. Social capital variables encompass social strata, networks, age, and gender, while mental health variables focus on symptoms related to depression, anxiety, stress, and general symptomatology. These variables were selected based on a comprehensive literature review and guidance from the Colombian Minister of Health and Social Protection’s 2020 strategy document on healthy cities and environments4.

Bogotá is divided administratively, politically, and territorially into 20 localities. Additionally, the city employs a socioeconomic division system based on urban and dwelling characteristics, classifying neighbourhoods into six social strata, with one representing the lowest charges in the public amenities services and six the highest. Due to their relevance, Suba and Usaquén, two of Bogotá’s most densely populated localities, were selected for this study. Within these localities, Prado, La Calleja, and Canódromo neighbourhoods were chosen as they represent Colombia’s middle-income class, with strata ranging from three to five. These neighbourhoods also exhibit distinct physical characteristics, including proximity to one of Bogotá’s main avenues, connecting the south with the north. This location not only influences the physical environment but also has significant socio-economic implications, affecting the daily dynamics and interactions within the area.

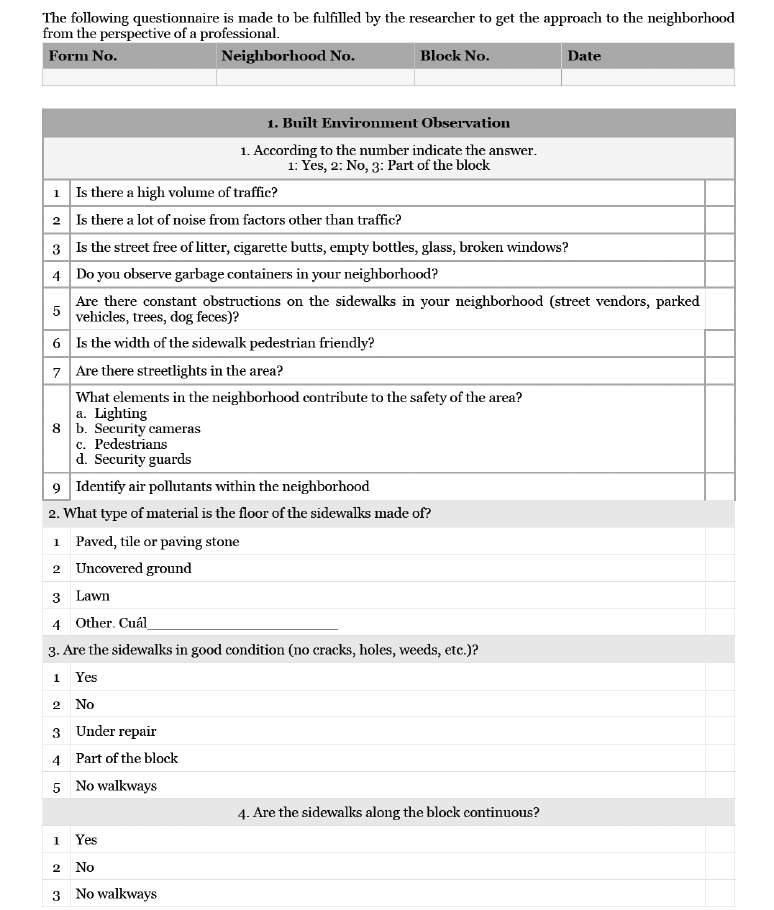

During the information verification phase, researchers corroborated secondary data from official sources, including the Secretary of Habitat, the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), the District Secretary of Planning, and the Secretary of Health and Social Welfare of Colombia. Field visits were conducted to validate the physical aspects of the environment, allowing researchers to confirm the accuracy of study variables by assessing neighbourhood quality directly. These site visits gathered primary data by observing how the study variables behaved on location.

The first step involved mapping the housing blocks within the study area, followed by developing visit forms (see Appendix 1. Site Visit Form) to systematically record critical environmental factors such as noise levels, elements contributing to safety or insecurity, sidewalk conditions, air quality, and the presence of waste materials like garbage, cigarette butts, bottles, and glass. A photographic record was also collected to visually document the site’s conditions, providing firsthand evidence to support the analysis.

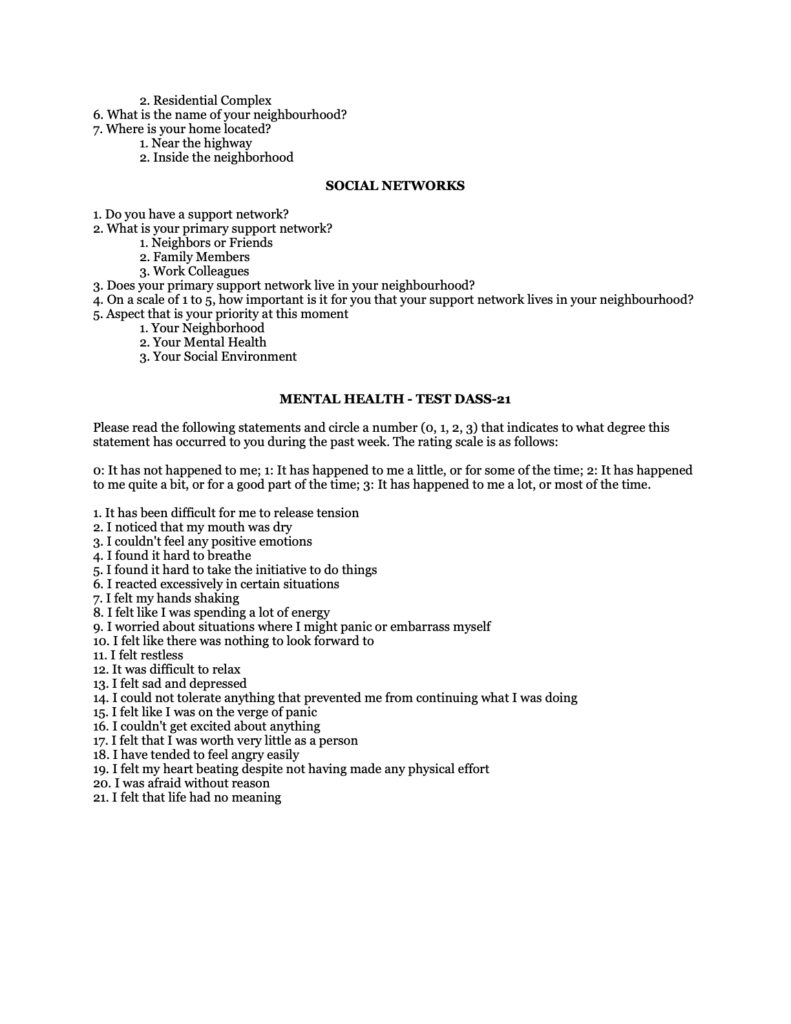

After validating the secondary data in situ, the next phase involved conducting one-on-one surveys (see Appendix 2. Survey and online publication https://hyd9s78a.forms.app/fieldresearchsurvey) to gather individual-level insights. The survey, consisting of 48 questions, took approximately 30 minutes per participant and aimed to capture perceptions of neighbourhood quality, socio-demographic characteristics, and mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and stress, using the DASS-21 test.

The DASS-21 test is a self-report questionnaire with explicit questions in which participants were asked directly about their physical and emotional experiences over the past week. Each item required participants to rate how frequently they had experienced specific symptoms using a scale from zero to three, where zero meant “It has not happened to me”, and three indicated “It has happened to me a lot, or most of the time.” For example, participants were asked whether they had difficulty relaxing, felt restless, or experienced physical symptoms like a dry mouth or a racing heartbeat. The explicit nature of the questions helps in directly assessing the presence and severity of anxiety, stress, or depression symptoms, such as trouble breathing, overreacting, or feeling sad. The test functions as a tool to measure the extent of these symptoms without diagnosing any mental health disorder. It provides an indication of the frequency and intensity of experiences related to anxiety (e.g., trembling hands, breathlessness), depression (e.g., lack of positive feelings, feeling worthless), and stress (e.g., difficulty relaxing, overreacting). This structured approach allowed for consistent and quantifiable data collection on mental health across diverse neighbourhoods, enabling researchers to gather data systematically and sensitively, considering the participants’ well-being.

The survey was conducted over three weeks using a free online platform with an interactive and user-friendly format. To ensure researchers’ safety, interviews were held during daylight hours on weekends and weekdays in public spaces such as parks, streets, and other open areas. Participants were approached directly in these locations, and the convenience of the online platform allowed them to respond through a link provided at the time of recruitment. The study included 41 residential blocks, with 34 located west of the avenue and seven to the east.

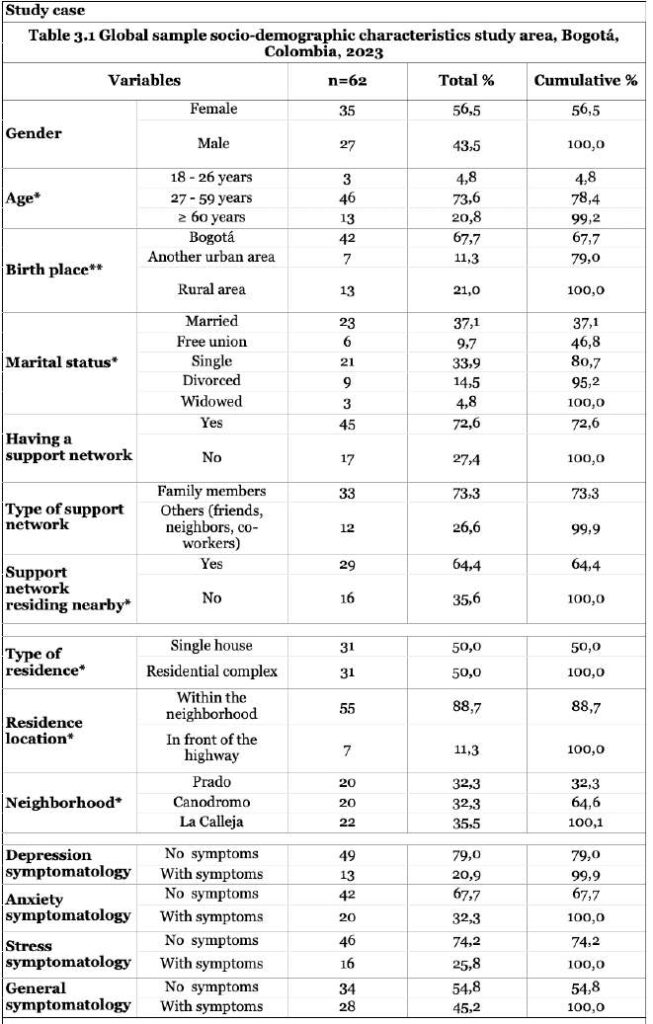

A diverse sample of 62 participants was collected, representing a broad range of socio-demographic backgrounds. The sample was 56% female and 44% male, with an age distribution of 4.84% for those aged 18-26, 74.19% aged 27-59, and 20.97% aged 60 or older. Most participants (79.03%) were born in Bogotá or another urban area, while 20.97% came from rural areas. Regarding marital status, 53.23% were married or living with a partner, while 46.77% were single, divorced, or widowed. Half of the respondents lived in single houses, and the other half resided in residential complexes. Most participants (88.71%) lived within the neighbourhood, while 11.29% lived near the main highway. Including participants living near the avenue and within the neighbourhood allowed for a detailed understanding of the impact of environmental variables like noise and air quality on mental health. The surveys also explored social support networks, with 72.58% of respondents indicating that they had a support network, primarily consisting of family members (53.23%). Regarding mental health, the reported symptomatology included depression (20.97%), anxiety (32.26%), stress (25.81%), and general symptoms (45.16%). These socio-demographic, physical, and social attributes varied across the three selected neighbourhoods, providing a comprehensive view of how different environmental and social factors influence mental health outcomes (See Appendix 3 Socio-demographic characteristics, physical and social attributes).

Analysis

The analysis unfolds through three distinct phases: descriptive, bivariate, and regression analysis. It utilises the JAMOVI free and open statistical and scientific software and consults with psychology, statistics, and epidemiology experts.

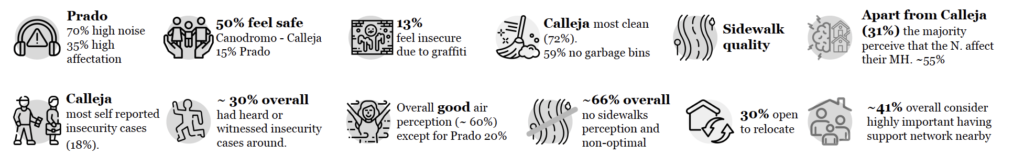

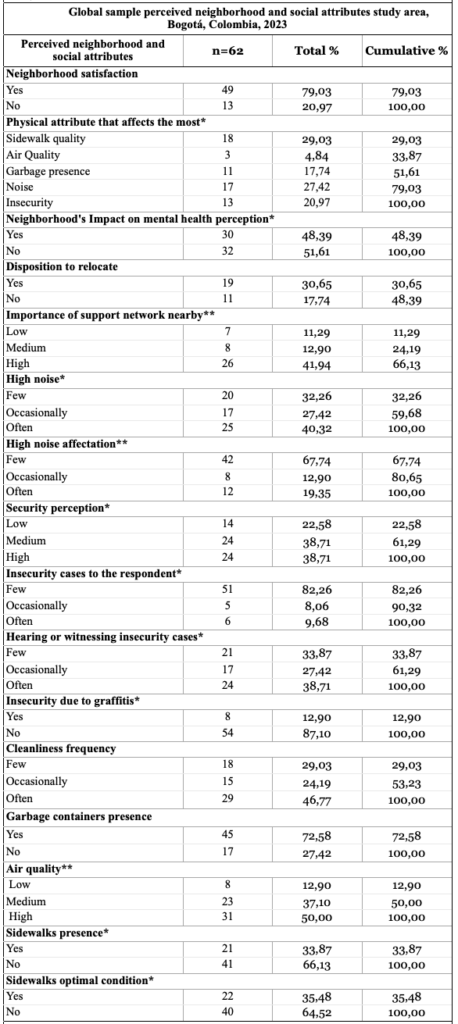

The first phase, descriptive analysis, organises data to reveal the proportions of residents’ perceptions concerning each variable. The data analysis revealed several key insights into how residents perceive their neighbourhood’s physical and social attributes. A majority of respondents, 79.03%, reported being generally satisfied with their neighbourhood, although a significant portion, 20.97%, expressed dissatisfaction, indicating room for improvement. Physical factors, such as sidewalk quality and noise, emerged as the most impactful, with 29.03% and 27.42% of residents identifying these as significant concerns, followed by insecurity and garbage presence (20.97% and 17.74%). Nearly half of the respondents (48.39%) felt that their neighbourhood impacted their mental health, closely related to physical and social conditions. Interestingly, 30.65% expressed a willingness to relocate due to its effects perception. Noise, in particular, affects 40.32% of the residents, with many also frequently hearing or witnessing incidents of insecurity (3.71%).

A significant portion (41.94%) of respondents value having a solid support network nearby, highlighting the importance of social cohesion. Cleanliness levels are generally positive, with nearly half of the respondents (46.77%) satisfied and 72.58% reporting the presence of garbage containers. However, infrastructure issues remain, particularly with sidewalks, as 66.13% indicated that sidewalks are absent, and 64.52% found existing sidewalks to be in poor condition.

Overall, the data shows that while many residents are satisfied, key areas such as noise reduction, safety, infrastructure improvements, and mental health considerations must be addressed to improve neighbourhood conditions and enhance residents’ quality of life.

The second phase of the analysis involves exploring the relationships between various environmental and social factors, such as air quality, noise, insecurity, garbage presence, and sidewalk quality, as indicators of neighbourhood conditions. In parallel, social capital variables include social strata, networks, age, and gender, while mental health variables centre around symptoms related to depression, anxiety, stress, and general mental health symptomatology.

To identify correlations between these variables, the study employs a statistical test using the P-value, which indicates the probability that a relationship between two variables is due to chance. In this context, the P-value measures the degree of association between an exposure factor (independent variable) and an outcome, such as a mental health symptom (dependent variable). The significance threshold for this study is set at 0.05. P-values greater than 0.05 suggest that any observed relationship between variables is likely due to chance and, thus, not statistically significant. On the other hand, P-values equal to or less than 0.05 indicate a statistically significant relationship, meaning there is strong evidence supporting the association.

Additionally, the study acknowledges P-values between 0.05 and 0.1 as indicators of indirect correlations. While these relationships are not as strong, they suggest a lighter association that could still impact mental health when considered alongside more robustly correlated variables. This nuanced approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how direct and indirect factors influence mental health outcomes in the neighbourhood.

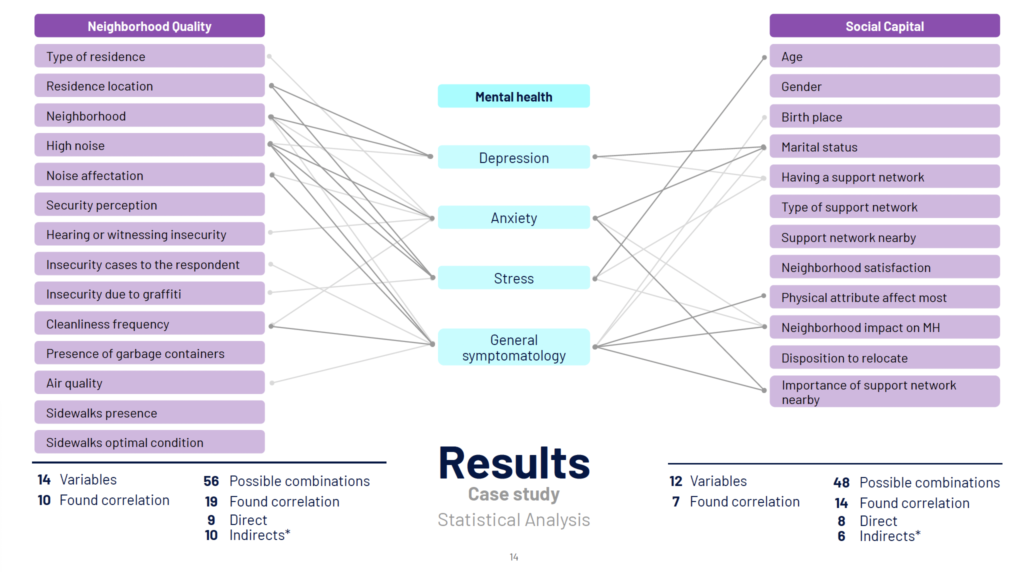

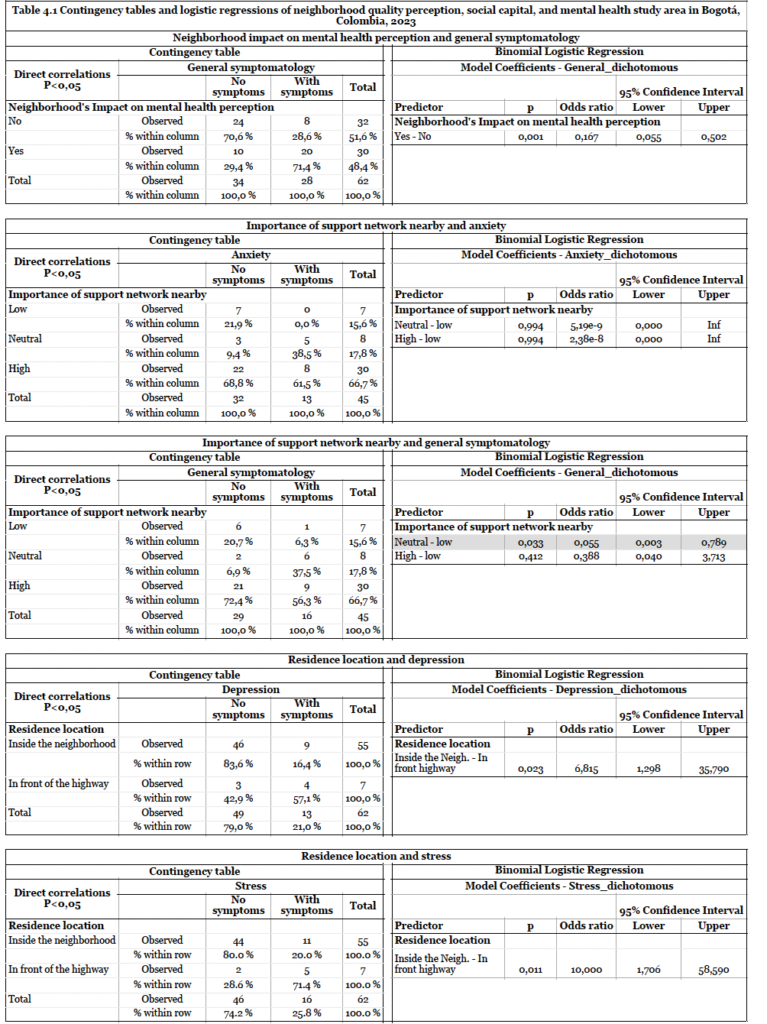

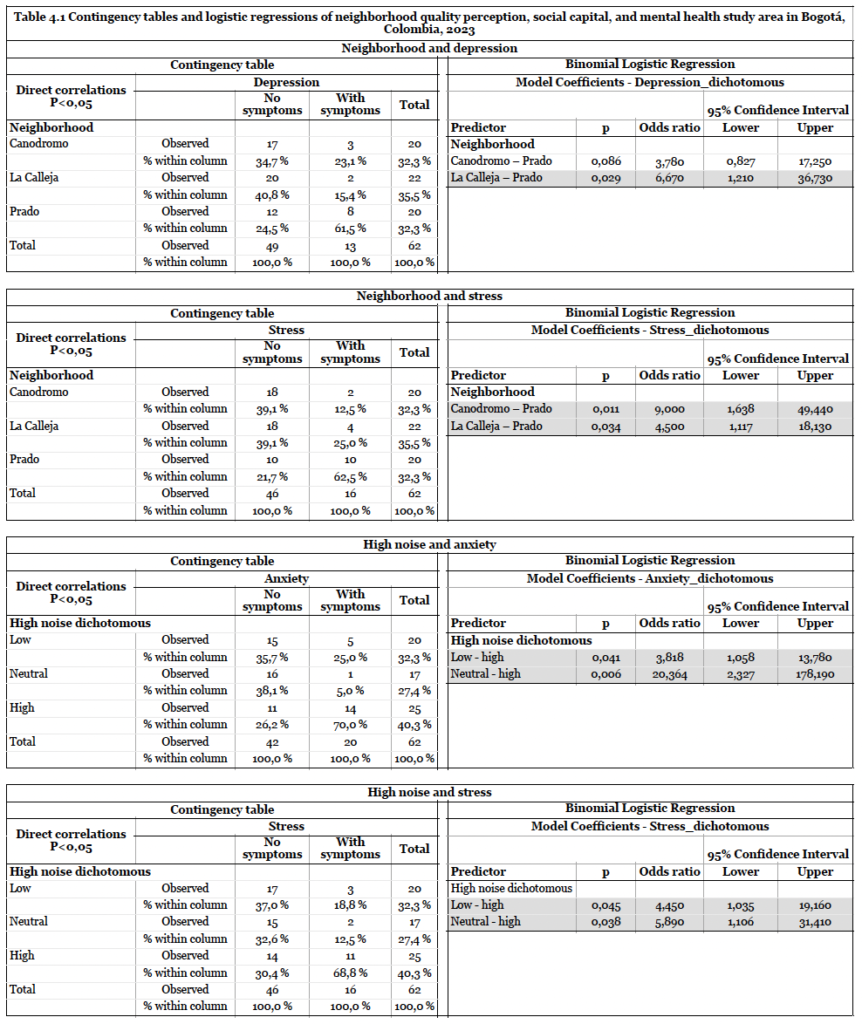

The bivariate analysis results show meaningful relationships between neighbourhood quality and social capital variables with mental health outcomes. Of the 14 neighbourhood quality variables assessed, ten displayed correlations, with 19 significant relationships out of 56 possible combinations—nine directly and ten indirectly. Significant findings in the physical environment include direct correlations such as the type of neighbourhood and residence location being linked to depression and stress. At the same time, the perception of high noise levels is associated with anxiety, stress, and general symptoms. Additionally, perceiving noise disturbances and poor neighbourhood cleanliness is linked to general symptoms. Indirect correlations were observed between high noise levels, insecurity cases, poor neighbourhood cleanliness, and anxiety. The type of neighbourhood and residence were also indirectly linked to anxiety and general symptoms. Noise disturbances in daily routines were associated with anxiety and insecurity, and air quality was related to general symptoms and, notably, perceived insecurity due to graffiti correlated with stress symptoms.

In analysing social capital variables, seven of the 12 studied showed correlations, with 14 significant relationships out of 48 possible combinations—eight direct and six indirect. Age correlated directly with stress, while marital status was linked to both depression and anxiety. Participants who felt impacted by physical aspects of their neighbourhood showed a direct association with general symptomatology. Additionally, not considering it essential to live near a support network was connected to anxiety and general symptomatology. Indirectly, birthplace and being single, widowed, or divorced were associated with general symptomatology, while lacking a support network correlated with depression and stress. Lastly, perceiving a negative neighbourhood impact on mental health was linked to anxiety and stress.

These findings underscore the intricate relationships between neighbourhood quality, social capital, and mental health outcomes. In this study, the neighbourhood type and location directly affect access to resources, safety, public spaces and tranquillity, with high-quality environments mitigating stress. At the same time, poorer conditions heighten the risks of depression and anxiety. Noise emerges as a significant disruptor linked to anxiety, stress, and general symptoms, as it might affect sleep and daily routines. Cleanliness and perceptions of insecurity, like graffiti and crime, also contribute to mental health issues, reinforcing feelings of vulnerability. Social capital plays a protective role, as having a strong support network helps individuals manage emotional challenges. At the same time, its absence increases vulnerability to mental health issues such as depression and stress. Demographic factors like marital status and age also have a significant impact on mental health, with younger individuals and those lacking stable social ties being more prone to anxiety and emotional instability.

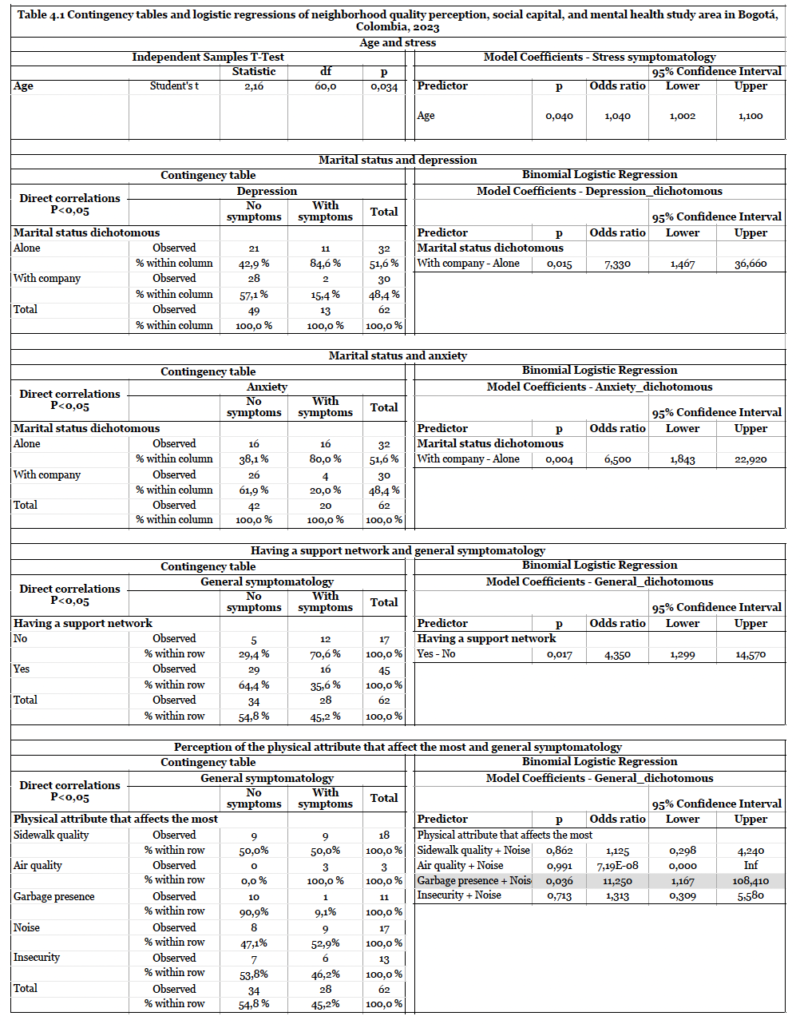

The final phase of the methodology, regression analysis, examined variables that had demonstrated direct relationships with mental health outcomes. Key environmental factors included high noise levels, which were associated with general symptomatology, anxiety, and stress. Neighbourhood type and residence location were also linked to stress and depression. In addition, the analysis explored how noise exposure and cleanliness frequency affected general mental health symptoms. Social factors were also considered, including the relationship between age and stress, marital status in connection with anxiety and depression, and the perception of being negatively affected by one’s neighbourhood, which was linked to general symptomatology. Another key finding was that those who believed living near a support network was unimportant were more likely to experience anxiety and general symptoms.

The regression analysis quantified the degree of impact these factors had on mental health by comparing groups with and without symptoms. This provided a clearer understanding of how environmental and social variables influence mental health disorders. Statistical measures such as odds ratios and confidence intervals were employed. The odds ratio, for instance, assesses the likelihood of a mental health disorder occurring due to specific exposures (such as poor environmental conditions) compared to those without such exposure.

Results showed that individuals who lived alone were more than six times as likely to develop depression and anxiety compared to those with companionship. Similarly, people lacking a support network were four times more likely to show general mental health symptoms. Environmental factors such as poor sidewalk quality, air pollution, garbage presence, and high noise levels were also significant. Notably, poor garbage management and high noise exposure increased the likelihood of general symptoms by 11 times. A strong support network reduced the possibility of depression, anxiety, and stress by 80%, while those who valued living near social support were 30% more likely to avoid mental health issues. Residents of polluted or noisy areas, particularly those near busy avenues, were six times more likely to suffer from depression. Exposure to high noise levels increased the risk of anxiety and stress by over four times, underscoring the harmful effects of noise pollution on mental well-being. Frequent cleanliness was linked to fewer symptoms, with individuals in cleaner environments being five times less likely to report mental health issues. A T-test (applied explicitly to quantitative data) revealed that older individuals tended to report higher stress levels.

When comparing the results between neighbourhoods, residents of Prado were nine times more likely to experience stress than those in Canodromo and four times more likely than those in La Calleja. Lower neighbourhood satisfaction, higher noise levels, insecurity, and poor air quality in Prado likely contributed to this. Prado also had the highest rates of mental health symptoms, with 40% to 65% of residents affected. In contrast, La Calleja had the fewest symptoms, the highest cleanliness perception, and the best neighbourhood quality scores (See contingency tables 3, 4, and 5 in the appendices for regression analysis results).

Site visits confirmed these findings, highlighting significant physical differences between neighbourhoods. In La Calleja and Canodromo, fewer homes were located near the main avenue or had green buffer zones. In contrast, many homes in Prado faced the road directly, exposing residents to higher noise levels and pollution. Prado also had fewer public spaces and well-maintained sidewalks, contributing to lower environmental quality and resident satisfaction.

The Neighbourhood Health-Impact Assessment Framework (NHIAF) pilot, despite its small sample size, underscored the significant effects of poor environmental and social conditions on residents’ well-being. While a more extensive study would be needed for statistically significant results, these initial findings are sufficient to prompt attention from city planners and policymakers.

Discussion

The results of this study have significant implications for urban planning, particularly in addressing environmental and social factors that impact mental health. The strong link between high noise levels and pollution with increased anxiety, stress, and depression underscores the need for noise control and pollution mitigation strategies. Urban planners should prioritise quieter zones and incorporate green buffer zones and soundproofing measures, particularly in residential areas, to minimise environmental stressors.

Social support networks are crucial for mental health, and the study highlights the importance of community-oriented designs that foster social interaction. Planners should incorporate communal spaces, public areas, recreational facilities, and mixed-use developments to promote social cohesion and strengthen community ties. The disparities between neighbourhoods like Prado and La Calleja reveal the need for equitable distribution of resources, public services, and facilities, addressing environmental and social inequalities.

Incorporating health impact assessments into the urban planning process is also essential. Planners and policymakers must integrate mental health considerations early in the design and policy stages to address the environmental and social factors influencing well-being. This holistic approach can help create healthier, more resilient communities.

The NHIAF (Neighbourhood Health-Impact Assessment Framework) is particularly valuable in quantifying subjective perceptions. Residents’ views on their neighbourhood and self-reported mental health symptoms offer insights into perceived realities rather than objective evaluations. Although these perceptions are based on personal experiences, the NHIAF’s strength lies in its ability to systematically analyse subjective data, allowing researchers to identify correlations between neighbourhood conditions and mental health.

It is crucial to note that this study identifies correlations, not causations. The observed associations between neighbourhood quality and mental health symptoms do not imply direct causality, as various factors contribute to mental health beyond a neighbourhood’s physical and social attributes.

Lastly, the study reveals limitations in current mental health assessment tools. Instruments like the DASS-21 focus on identifying mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression but do not measure positive attributes like resilience and tranquillity. This limitation reflects a broader issue in the healthcare system, where the emphasis is often on diagnosing and treating illnesses rather than promoting overall mental well-being. The findings suggest a need to shift from solely treating mental health disorders to actively promoting mental health through comprehensive assessments that consider positive well-being factors.

Conclusion

This research provides essential guidelines for investigating and measuring the relationship between neighbourhood quality and mental health. The proposed method and case study offer a flexible and comprehensive data collection and analysis framework, supporting ongoing updates and refinements. Despite its exploratory nature and small sample size, the study contributes valuable insights into assessing the built environment’s impact on mental health in the Global South.

The findings emphasise the considerable influence of built environment quality on mental health, with physical factors such as noise, air pollution, and proximity to highways showing a stronger correlation with mental health outcomes than social factors. This may be partly due to the limited number of questions regarding social factors, which warrants further investigation. A notable observation is that residents often normalise suboptimal environmental conditions, unaware of their health impacts. For instance, in Prado, residents did not perceive noise levels as disruptive in daily activities, even though their residences were situated on a busy road, which the analysis showed had a significant impact.

The study also reveals that differences in social strata extend beyond physical characteristics, highlighting variations in geographic and socio-economic dynamics and their effects on mental health. Challenges such as limited data collection due to security concerns and restricted access to gated communities affected the sample’s representativeness and the overall findings. This suggests that individuals adapt to less-than-ideal environmental conditions over time, even when statistical data indicates their detrimental effects.

Further Research

Further research is needed to better understand the relationships between the built environment and mental health. This involves refining the methods used and expanding the study sample. A larger, more representative sample in each neighbourhood would allow for more statistically significant comparisons, allowing researchers to analyse each variable more accurately and apply the method across various neighbourhoods with similar social conditions. Doing so would enable the comparison of the built environment’s impact on mental health in different areas of a city, helping to generalise findings more broadly.

Moreover, future studies should incorporate subjective and objective data to understand how neighbourhood conditions affect mental health comprehensively. While perception-based studies offer valuable insights into how people experience their environment, they are not substitutes for concrete, measurable data. Combining residents’ subjective accounts with environmental quality assessments or clinical mental health evaluations would offer a more balanced perspective. This approach would allow for a more nuanced understanding of how environmental and social factors interact, opening the door to more targeted urban health interventions.

Additionally, interdisciplinary collaboration should be prioritised to create a standardised framework for assessing the built environment’s impact on mental health. This could be enriched by including open-ended questions in future studies to capture broader social dimensions. Furthermore, in-depth interviews would provide the necessary qualitative data to explore the complexities of how people’s environments influence their well-being. This combination of qualitative and quantitative methods would help advance research in this field and inform more effective urban planning and policy decisions.

Appendices

References

1 United Nations. Population of South America (2023) – Worldometer [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/south america-population/

2 Clark, C. et al. (2007) ‘A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of the built and physical environment on mental health’, Journal of Public Mental Health, 6(2), pp. 14–27. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/17465729200700011.

3 United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. 2017 [cited 2023 Jul 17]. SDG Indicators. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/

4 Ministerio de salud y protección social (2020) ‘Guía práctica de herramientas para la implementación de la estrategia de ciudades, entornos y ruralidades saludables (CERS)’.

Bibliography

1 Bhugra D, Ventriglio A, McCay L, Castaldelli-Maia J. Urban Mental Health [Internet]. Oxford University Press; (2019). (Oxford cultural psychiatry series). Available from: https:// books.google.com.eg/books?id=Bc-aDwAAQBAJ

2 Corral-Verdugo V, Pinheiro JQ. Environmental psychology with a Latin American taste. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2009 Sep 1;29(3):366–74.

3 World Health Organization, Sergey V. Mental health [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health

4 Zumelzu, A. and Herrmann-Lunecke, M.G. (2021). ‘Mental Well-Being and the Influence of Place: Conceptual Approaches for the Built Environment for Planning Healthy and Walkable Cities’, Sustainability, 13(11), p. 6395. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116395.

5 Park, S.-H. and Mattson, R.H. (2009). ‘Therapeutic Influences of Plants in Hospital Rooms on Surgical Recovery’. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.44.1.102.

6 Ministerio de salud y protección social. Guía práctica de herramientas para la implementación de la estrategia de ciudades, entornos y ruralidades saludables (CERS). 2020.

7 Ritchie H, Roser M. Urbanization. Our World in Data [Internet]. 2018 Jun 13 [cited 2023 Jun 13]; Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization

8 Kaur P., Stoltzfus J, Yellapu V. Descriptive statistics [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 Aug 7]. Available here

9 Sandilands D (Dallie). Bivariate Analysis. In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014 [cited 2023 Aug 7]. p. 416–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_222