“L’essentiel est invisible aux yeux”– Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Air is the invisible asset that sustains life. Despite its necessity it is mostly taken for granted until awareness is raised on how it can be, or is compromised. The threat of the COVID-19 pandemic stimulated thought on air quality due to the airborne transmission of the SARS-COV2 virus. This added to already growing awareness of the deleterious effects of air pollution on climate change and human health.

In assessing the quality of air, one should consider two main categories:

- Outdoor Air Quality: The air quality of the the air outside buildings, from ground level to several miles above the Earth’s surface.1

- Indoor Air Quality: The air quality of the air within and around buildings and structures, especially as it relates to the health and comfort of building occupants.2

How does impaired air quality impact human health?

Poor air quality has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients with respiratory, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular concerns.3 Increasingly, studies are highlighting the deleterious effects of poor air quality on mental health outcomes, foetal development, premature births in pregnancy, decreased neurodevelopment and cognitive ability in children, and future lifetime risk of chronic diseases in later life.4,5

Designing for Air Quality

With regards to the acceptable ranges for air quality, reference can be made to the International Society of Indoor Air Quality and the Climate STC 34 Database which contains global and country specific standards for both outdoor and indoor air components.6 Most individuals spend 80-90% of their lives indoors, most of which is in their homes.7 As a result of this, both residential and industrial buildings should be adequately designed to ensure healthy air quality for its occupants. Many buildings currently rely on ventilation and air condition (HVAC) systems8, but future proofing our buildings means ensuring long term maintenance of optimal air quality for occupants.

(Safiya Cummings, 2024)

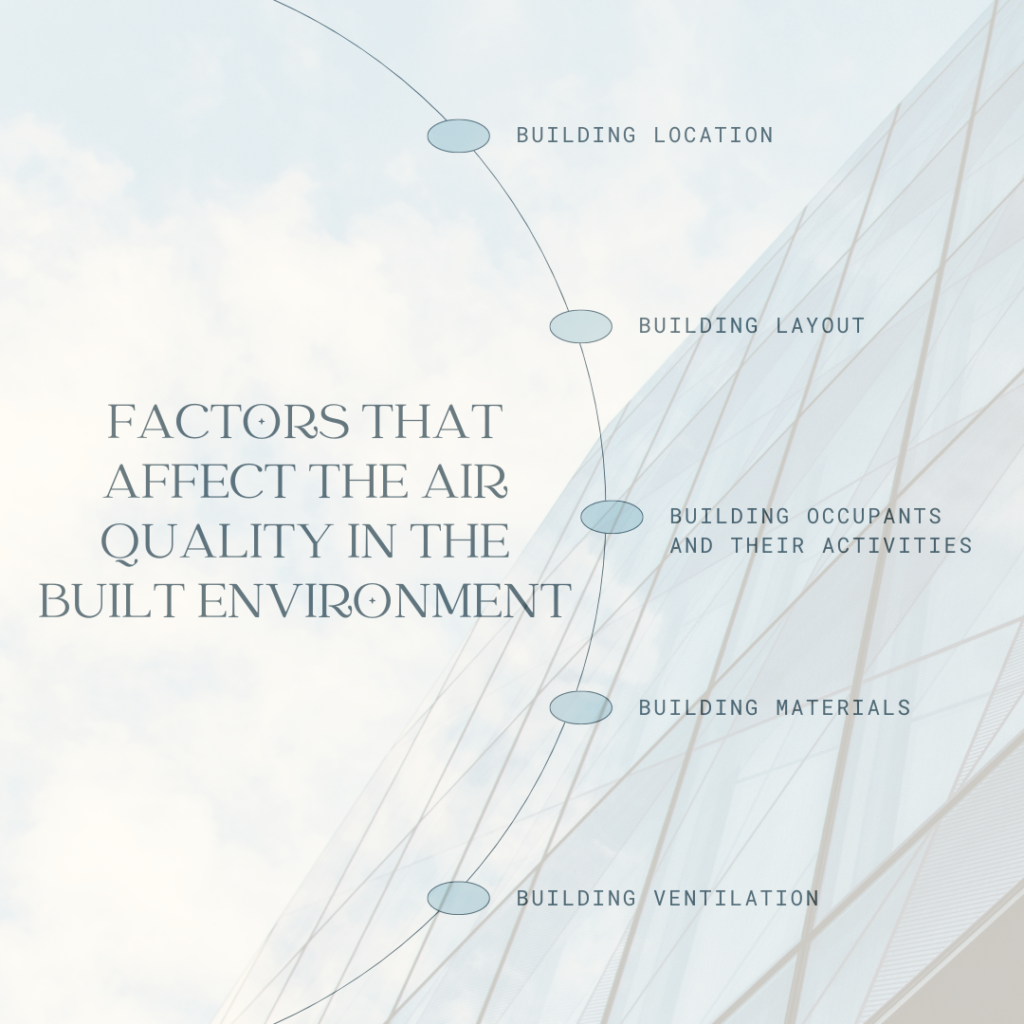

How can we optimise our buildings for air quality?

Building Location

Unless pre-planning is conducted to intentionally address occupant wellbeing, the location of the building is usually a non-modifiable factor in the design process. Therefore mechanisms must be established to combat the effects of the environment that the building is placed in.

During a project’s feasibility stage, measurements should be recorded over a period of time to account for the variability of air quality in the location. If external factors such as an industrialised zone with high amounts of air pollution is identified, the client should be alerted to the potential implications for their building’s occupants before proceeding with the project.

In the project planning process, trees may be added to the landscaping profile of the building as a natural resource for improving air quality and complimentary environmental adjuncts may be established to encourage active transport to the building to reduce vehicular emissions.

In an already established project, outdoor air monitors can be installed to identify sources of air pollutants and inform individuals as to days or locations where air quality is dangerous. Additionally the building can be screened for ways in which the site can be enhanced to improve air quality through space use modification, landscaping or building adjuncts.

Building Layout and Occupants and their Activities

Factors in the layout of a building can tie into the use of the facility, the duration of time occupants spend in key spaces, as well as movement between spaces. In buildings, every room’s defined function is associated with specific activities – such as cooking within the kitchen area of a home, or the use of candles or incense in places of worship, the use of cleaning agents in the bathroom or pet dander in the pet area. These are all examples of factors that affect air quality.

Whilst it is near impossible to remove all sources of air pollution, consideration of air flow, air purification and occupant activities should be utilised in spatial planning. Consider placing activities that degrade air pollution farther from where occupants spend more time. Furthermore, installation of air quality monitors within and between these zones can alert building occupants when levels are unhealthy. This aspect of the planning process aims to minimise exposure to unavoidable and non-modifiable sources of air pollution.

Building Materials

The key source of air pollution from building materials lies within volatile organic components (VOC).9 Volatile organic components are compounds that have a high vapour pressure at room temperature.10 These may be released from paint, finishes and furnishings. The Living building Challenge has developed a Red List representing the “worst in class” substances prevalent in the building industry that pose serious risks to human health and the environment11 , this list may be helpful in identifying some volatile organic components. Designers should explore low VOC options in their products and inform consumers of their benefits.

Another option for the selection of building materials is through the awareness and utilisation of bio-based construction materials. Whilst evidence leans towards increased sustainability and environmental benefits, further studies are needed to evaluate the long term use of these materials and how their exposures affect their individual VOC emissions.12

Building Ventilation

Ventilation describes bringing outside air into a space by mechanical, natural, or mixed-mode approaches.13 With increased environmental awareness there is a greater demand for natural ventilation strategies in preference to automated strategies using the HVAC systems.14 Natural ventilation is only viable when natural forces are available13 and is complimented by design elements which promote air circulation such as windows, doors and facade perforations, or endeavours featuring partitions and curving walls. Yet, cost is a key factor in the installation and maintenance of mechanical and mixed mode ventilation systems.13 A ventilation system that works well must be in harmony with the project’s surroundings, which includes the material, architecture, location, and usage patterns of the users.

Future Planning

Air Quality is crucial to human health and as the value of the invisible life-force increases with time, enhancing the availability of clean air through design is only a natural progression in future proofing our buildings. Conscious decision making and planning is the first step in providing improved air quality for all.

References

1 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Outdoor air quality. Retrieved September 29, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/report-environment/outdoor-air-quality

2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Introduction to indoor air quality. Retrieved September 29, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/introduction-indoor-air-quality

3 Miller M. R. (2022). The cardiovascular effects of air pollution: Prevention and reversal by pharmacological agents. Pharmacology & therapeutics, 232, 107996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107996

4 Gheissari, R., Liao, J., Garcia, E., Pavlovic, N., Gilliland, F. D., Xiang, A. H., & Chen, Z. (2022). Health Outcomes in Children Associated with Prenatal and Early-Life Exposures to Air Pollution: A Narrative Review. Toxics, 10(8), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics10080458

5 Bhui, K., Newbury, J. B., Latham, R. M., Ucci, M., Nasir, Z. A., Turner, B., O’Leary, C., Fisher, H. L., Marczylo, E., Douglas, P., Stansfeld, S., Jackson, S. K., Tyrrel, S., Rzhetsky, A., Kinnersley, R., Kumar, P., Duchaine, C., & Coulon, F. (2023). Air quality and mental health: evidence, challenges and future directions. BJPsych open, 9(4), e120. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.507

6 International Society of Indoor Air Quality and Climate. (n.d.). Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) guidelines. https://ieqguidelines.org

7 Mannan, M., & Al-Ghamdi, S. G. (2021). Indoor Air Quality in Buildings: A Comprehensive Review on the Factors Influencing Air Pollution in Residential and Commercial Structure. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(6), 3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063276

8 Dimitroulopoulou, S., Dudzińska, M. R., Gunnarsen, L., Hägerhed, L., Maula, H., Singh, R., Toyinbo, O., & Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U. (2023). Indoor air quality guidelines from across the world: An appraisal considering energy saving, health, productivity, and comfort. Environment international, 178, 108127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.108127

9 Jin, S., Zhong, L., Zhang, X., Li, X., Li, B., & Fang, X. (2023). Indoor Volatile Organic Compounds: Concentration Characteristics and Health Risk Analysis on a University Campus. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(10), 5829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105829

10 Epping, R., & Koch, M. (2023). On-Site Detection of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 28(4), 1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28041598

11 International Living Future Institute. The Red List. https://living-future.org/red-list/

12 Raja, P., Murugan, V., Ravichandran, S., Behera, L., Mensah, R. A., Mani, S., Kasi, A., & Balasubramanian, K. B. (2023). A review of sustainable bio-based insulation materials for energy-efficient buildings. Materials and Energy, 28 May. https://doi.org/10.1002/mame.202300086

13 Atkinson J, Chartier Y, Pessoa-Silva CL, et al., editors. Natural Ventilation for Infection Control in Health-Care Settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. 2, Concepts and types of ventilation. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK143277/

14 Li, W., Xu, X., Yao, J., & et al. (2024). Natural ventilation cooling effectiveness classification for building design addressing climate characteristics. Scientific Reports, 14, 16168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66684-9