Simone Weil, in her work The Need for Roots, asserts, “[t]o be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul… Human beings have roots by virtue of their real, active, and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape particular treasures of the past and particular expectations for the future.” This profound connection is crucial beyond individual well-being, affecting health and resilience at the neighborhood level. As designers it is critical to ask, how can we design for this connection? Especially amidst the contours of the ongoing housing crisis? After all, a connected community can better respond to adversity through reciprocal social networks, care, and investment in place.

Weil’s concept of rootedness is increasingly challenged by urban life. People are more mobile than ever, often driven by economic pressures. This heightened mobility, while sometimes offering new opportunities, often comes at the cost of severing ties to familiar places and people. The issue is exacerbated as housing becomes more unaffordable, and many are forced out of their homes and communities, subsequently weakening the bonds that Weil deemed so essential. As instability in housing increases, the resulting displacement undermines the ontological security and belonging necessary for meaningful community engagement. A lack of housing security can create a sense of instability that prevents people from connecting deeply with the places and people in their lives (Dupuis and Thorns 1988; Hiscock et al 2001; Hulse and Saugeres 2008). The design of more temporary accommodations can also contribute to feelings of transience and lack of personal investment (Boyd et al. 2016; Manson, Kerr, and Fast 2022; Manson and Fast 2024).

Conscious design of the spaces in which we live and work plays a vital role in collective well-being and rootedness, a concept increasingly supported by research and accepted by forward-thinking practitioners. At Human Studio Architecture and Urban Design1, we strive to design for well-being and social connection in every project. Our work exists within challenging contexts of the Canadian housing crisis as we look to co-create affordable and supportive social housing projects across the province of British Columbia. Standing on the shoulders of local residents and organizations like Happy Cities and Hey Neighbour Collective, we aim to learn from research, conversation, and practice how architecture can help our communities grow to be more resilient through difficult economic and spatial constraints. By using evidence-based research to design buildings that foster connection, we contribute to the exchange of ideas, placemaking, and the growth of stronger, healthier networks better equipped to thrive in good times and navigate crises when challenges arise.

Our office sits at the edge of Vancouver’s Olympic Village, an urban revitalization project built for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Canada. This master-planned community with luxury condos, public squares, a waterfront seawall, and green spaces starkly contrast to the nearby Downtown Eastside (DTES). One of Vancouver’s oldest neighborhoods, the DTES is well known for its ‘highly visible’ housing insecurity and homelessness. Harsh lines of private ownership, privately policed “public” spaces, and defensive architecture separate these two communities. Olympic Villages across the globe often serve as image-making exercises for entrepreneurial cities such as Vancouver, showcasing a curated urban experience that would be otherwise difficult to design for in a broader city context. As noted by Muñoz (2006), “the architecture of the Olympic Villages manifests the ambition to reproduce […] the urban models and architectural proposals that, due to rigidity and difficulties, cannot be put into practice in the real space of the city.” These projects attract significant public buy-in and investment, the likes of which are rarely seen for other forms of development such as public housing.

Photo credit: Mike-Seehagel

The latest addition to the Olympic Village community is a temporary modular housing complex installed by the City of Vancouver to address the housing and homelessness crises. The City has installed 13 such temporary modular buildings across the city since 2017. These low-rise buildings make use of leftover spaces and fallow sites of future development to provide short-term relief, while more permanent housing developments progress through complex approval processes. Temporary modular housing offers much-needed safe shelter for those in need, with studio-sized units, self-contained kitchenettes, private bathrooms, and access to critical support services. However, the speed and affordability of construction come with tradeoffs; the resulting acoustics, lighting, materials, blind corners, and tight square footage can create contested spaces and an institutionalizing experience for residents (Manson, Kerr and Fast 2022). This can be especially challenging for marginalized residents and those recovering from trauma (Harvey 1996; Friesinger et al. 2019). The speed at which temporary modular projects can be delivered offers a necessary immediate response for those in need. However, they introduce a risk that a speed-over-quality approach will carry forward into broader housing strategies, sacrificing design for longevity and connection to meet the economic and political pressures of our time. British Columbia and Canada as a whole are currently directing significant political will and attention toward the housing crisis, with increased funding, blanket rezoning, and reduced red tape (Government of British Columbia 2024). While maximizing unit counts and new build statistics is seen as a solution to cool heated markets and boost political favor, it is crucial to consider the quality and character of housing being provided along the way.

Design for connection inherently requires more space; slightly wider hallways to avoid conflict, distributed amenity spaces to allow smaller communities to form, ample green space and connection to nature, thickened thresholds between public and private, psychologically safe places to pause and just “be” (Williams 2005; McLane and Pable 2020). These elements foster social interactions and a sense of community, but often at the cost of square footage that could be used for additional or more generous units. This tension between the desire for connection and the limitations of space forces us to carefully consider how we prioritize and integrate these essential elements. How can we as designers shape richer, more connected spaces for well-being when space itself is at such a premium? How do we measure the value of conscious design? How do we provide much-needed conscious design elements when they could come at the cost of a unit of housing?

There are no easy answers here. At Human Studio, one strategy we are exploring is re-evaluating the concept of ‘amenity space.’ Typically, amenity spaces are areas within a building or development designed for communal use by residents, such as lounges, gyms, or green spaces. While they are usually excluded from Floor Space Ratio (FSR) calculations—a critical metric capping building density—amenity spaces can provide much-needed breathing room without reducing allowable housing unit square footage. Instead of relegating amenities to leftover spaces and neglected basement ‘party rooms,’ they can be distributed more critically throughout a project. In this way, meaningful shared spaces only possible in rarified development and investment conditions like Olympic Villages can be integrated thoughtfully into design for the everyday across the city.

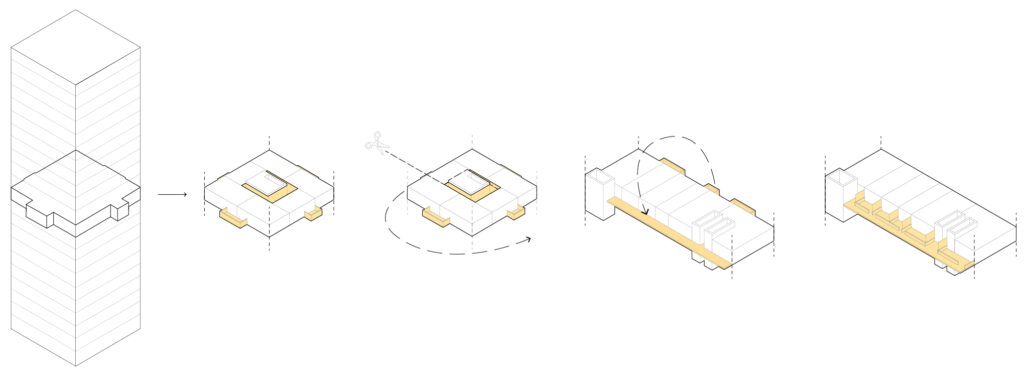

We put this approach into practice on 800 Commercial, a mixed-income affordable housing project in East Vancouver that will be operated by Entre Nous Femmes Housing Society. At its core, 800 Commercial aims to provide two fundamental design elements for meaningful engagement: firstly, space to connect with neighbors; and secondly, a sense of comfort, belonging, and ease to help people feel more open to that connection. In this way, it seeks to foster “real, active, and natural participation in the life of a community” to support the growth of vibrant, interconnected, and resilient roots. The private balconies seen on the typical Vancouver tower typology, excluded from FSR calculations, are flipped to pair with the single-loaded exterior circulation corridor running the length of the building. The result is shared space inspired by Lacaton & Vassal’s Transformation of 530 Dwellings in Bordeaux, with thickened transitions from public to private space, and opportunities to encounter neighbors more regularly (Lacaton & Vassal 2011). A diverse unit mix, with a range of studios to three-bedroom suites on each floor, is intended to foster interaction between diverse groups of people as research suggests that friendships form between diverse groups when they live closer together, and that semi-public shared spaces are necessary for those groups to meet and interact (Nahemow and Lawton 1975; Peterson 2017).

The design of 800 Commercial hinges on the key research finding that architectural “depth” improves sociability and mental health (Evans, Lepore, and Schroeder 1996). Typical residential buildings draw jarring boundaries between units; in the space of a few inches, one is thrust from a private realm into an ambiguously shared public corridor, reducing overall comfort and sense of belonging in circulation space. In contrast, a clear gradient of spaces from public to private helps people feel safe and in control (Williams 2005). Communal space is beneficial, but can be highly contested if participation is involuntary or ownership is murky; clear boundaries of semi-private space, and opportunities for choice are critical for enticing people into social shared spaces. This allows them to retain personal autonomy and preference for social exposure (Rollings and Bollo 2021).

Renderings by Human Studio

800 Commercial’s focus on creating a welcoming, shared corridor responds to findings that most social interactions occur in circulation and activity spaces (Huang 2006). In contrast to a typical artificially lit, hermetically sealed, double-loaded corridor scheme, the single-loaded corridor is framed by open archways. This allows for a unique sense of identity and place while framing city views, bringing in lots of natural light and air to create a more comfortable experience. It also gives each unit double exposure, providing both morning light and sunset views with cross-ventilation. The resulting “front porch” allows residents to extend their personalities into shared spaces and choose how much social exposure they would like. This meets the inherent territorial need for people to signal their presence and claim ownership over the semi-private space with furniture and decorations (Goffman 1971). It also provides a sense of “prospect-refuge”, a concept in environmental psychology that refers to a space where one feels both safely enclosed, while having a clear view of their surroundings (Appleton 1975). This meets the psychological need to feel one’s back is protected, while providing space to people-watch from the comfort of their own space (Gehl 2010).

While FSR is one measure of spatial efficiency, it is only one possible metric of human connection and success in these spaces. Other important considerations include the quality of social interaction, access to natural light, and the sense of privacy and security. Vancouver City Council’s recent approval of this project, particularly its emphasis on social spaces, represents a significant shift towards valuing human connections within urban design. Their endorsement indicates a broader recognition of the importance of rootedness and well-being in housing. It’s a powerful example of how local governments can champion design strategies that prioritize social interaction, even when they challenge conventional development norms or require adjustments to established metrics. For instance, revisiting FSR calculations to include certain types of amenity spaces without penalizing overall unit counts could encourage more designs that incorporate communal areas. Additionally, policies that incentivize the integration of nature, like green spaces and biophilic design, could further support rootedness and connection to place. Giving policymakers and administrative bodies tools to support conscious design decisions is an important element in designing a truly sustainable and resilient housing supply.

An ontological shift from politically motivated quantitative metrics, like unit count, toward holistic accounts of well-being is crucial for shaping a more rooted and resilient city. A truly sustainable building fosters a sense of connection to place and community, with investments in higher quality, dignified housing paying dividends in longevity and well-being. In the midst of a housing crisis, it’s challenging but essential to prioritize health and well-being in housing design. By integrating conscious design principles, seeking innovative solutions, and fostering collaboration among developers, policymakers, and designers, we can create environments that support mental, physical, and community health. This approach ensures that the rush to build more housing does not come at the expense of residents’ quality of life and long-term community resilience, transforming our living spaces into vibrant, thriving communities for all—not just during high-profile events like the Olympics, but as a standard for everyday life.

Endnotes

1 Human Studio is an architectural practice based on the unceded ancestral territory of the Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh, and Squamish peoples in so-called Vancouver.

Bibliography

Appleton, Jay. The Experience of Landscape. New York: Wiley, 1975.

Boyd, Jade, David Cunningham, Solanna Anderson, and Thomas Kerr. “Supportive Housing and Surveillance.” The International Journal on Drug Policy 34 (2016): 72-79.

Dupuis, Ann, and David C. Thorns. “Home, Home Ownership and the Search for Ontological Security.” The Sociological Review 46, no. 1 (1998): 24-47.

Evans, Gary W., S. Lepore, and Alex Schroeder. “The Role of Interior Design Elements in Human Responses to Crowding.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70, no. 1 (1996): 41-46.

Friesinger, Jens Georg, Alain Topor, Tormod Dagane Bøe, and Inger Beate Larsen. “Studies Regarding Supported Housing and the Built Environment for People with Mental Health Problems: A Mixed-Methods Literature Review.” Health & Place 57 (May 2019): 44-53.

Gehl, Jan. Cities for People. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2010.

Goffman, Erving. Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. New York: Harper & Row, 1971.

Government of British Columbia. “B.C. Government Addressing Housing Affordability Challenges.” Last modified August 24, 2023. https://news.gov.bc.ca/factsheets/bc-government-addressing-housing-affordability-challenges.

Harvey, Mary R. “An Ecological View of Psychological Trauma and Trauma Recovery.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 9, no. 1 (1996): 3-23.

Hiscock, Rosemary, Ade Kearns, Sally Macintyre, and Anne Ellaway. “Ontological Security and Psycho-Social Benefits from the Home: Qualitative Evidence on Issues of Tenure.” Housing, Theory and Society 18, no. 1-2 (2001): 50-66.

Huang, Shu-chun Lucy. “A Study of Outdoor Interactional Spaces in High-Rise Housing.” Landscape and Urban Planning 78, no. 3 (2006): 193-204.

Hulse, Kath, and Lise Saugeres. “Housing Insecurity and Precarious Living: An Australian Exploration.” Housing Studies 23, no. 7 (2008): 1105-1124.

Lacaton & Vassal. “Transformation of 530 Dwellings.” Accessed August 26, 2024. https://www.lacatonvassal.com/index.php?idp=80.

Manson, Daniel, Thomas Kerr, and Danya Fast. “I’m Just Trying to Stay: Experiences of Temporal Uncertainty in Modular and Supportive Housing among Young People Who Use Drugs in Vancouver.” The International Journal on Drug Policy 110 (2022): 103893.

Nahemow, Lucille, and M. Powell Lawton. “Similarity and Propinquity in Friendship Formation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 32, no. 2 (1975): 205-213.

Peterson, Melike. “Living with Difference in Hyper-Diverse Areas: How Important Are Encounters in Semi-Public Spaces?” Social & Cultural Geography 18, no. 8 (2017): 1067-1085.

McLane, Yelena, and Jill Pable. “Architectural Design Characteristics, Uses, and Perceptions of Community Spaces in Permanent Supportive Housing.” Journal of Interior Design 45, no. 1 (2020):

Muñoz, Francisco. “Olympic Urbanism and Olympic Villages: Planning Strategies in Olympic Host Cities, London 1908 to London 2012.” The Sociological Review 54, no. 2 (2006): 175-187.

Rollings, Kimberly A., and Christina Bollo. “Permanent Supportive Housing Design Characteristics Associated with the Mental Health of Formerly Homeless Adults in the U.S. and Canada: An Integrative Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12 (2021): 6487.

Weil, Simone, and T. S. Eliot. The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties toward Mankind. Translated by Arthur Francis Wills. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955.

Williams, Joycelyn. “Designing Neighbourhoods for Social Interaction: The Case of Cohousing.” Journal of Urban Design 10, no. 2 (2005): 195-227.