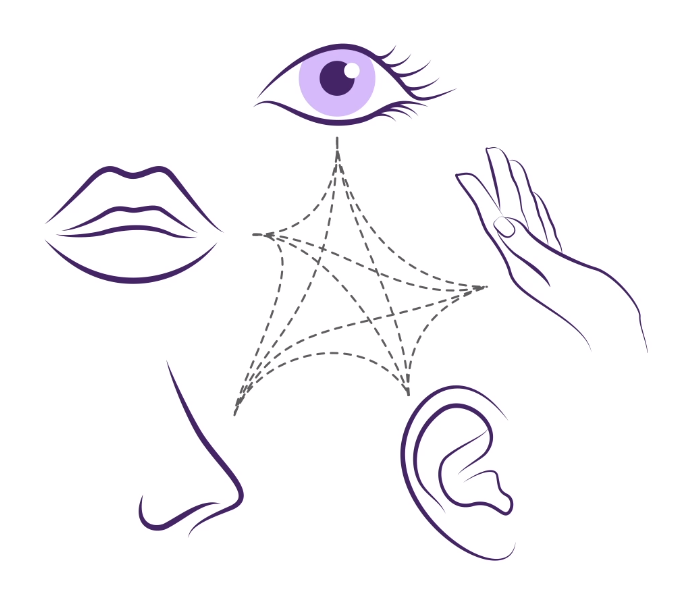

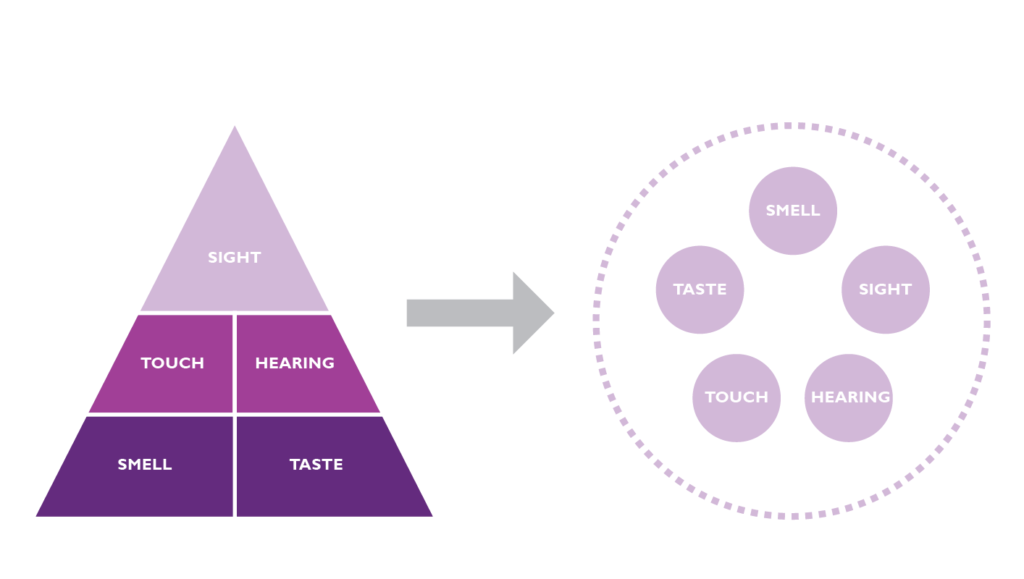

We understand our surroundings through a seamless blend of our senses—sight, touch, sound, smell, and taste (Lackner & Dizio)—and these cross-modal associations help us navigate the world around us (Newell) [Figure 1]. Our environment speaks to us in layers, and it’s this multisensory dialogue that allows us to truly connect with the spaces we inhabit.

Despite the interdependence between our senses, the practice of architecture historically prioritizes sight above the rest (Blesser and Salter) [Figure 2]. This methodology in architectural practice results in sensory-deprived environments in buildings that are proven to have detrimental effects on public health outcomes (Renner and Rosenzweig). The rich tapestry of sensory stimuli that characterized the outdoors has been gradually filtered through walls and windows, altering how we interact with our surroundings and how our buildings are designed.

From the earliest stages of life, our cognitive development is profoundly shaped by the environments we inhabit. Studies reveal that sensory-deprived settings can hinder cognitive associations and learning abilities in children (Johnson et al.; Lickliter; Grubb and Thompson). Moreover, the sensory monotony of our built environment also creates sensory inequities in buildings, making it more difficult—or even impossible—for those with sensory impairments to navigate the world. Integrating holistic “sensory design supports everyone’s opportunity to receive information, explore the world, and experience joy, wonder, and social connections, regardless of our sensory abilities” (Lupton and Lipps). The potential to create spaces that genuinely engage all the senses could be transformative, offering a more equitable and enriching experience for everyone [Figure 2].

One of the most underrepresented senses in the built environment is the sense of smell, also referred to as olfaction. By consciously integrating scents into architecture and interior design, we can craft intentional scent landscapes or ‘Scentscapes,’ a term coined by Andrea Lipps (Lipps), that immerse occupants in curated olfactory environments. These designed Scentscapes challenge the traditional sensory hierarchy in architecture, providing a richer, more balanced sensory experience that enhances overall health and well-being for those who inhabit these spaces.

THE IMPACT OF OLFACTION ON WELL-BEING

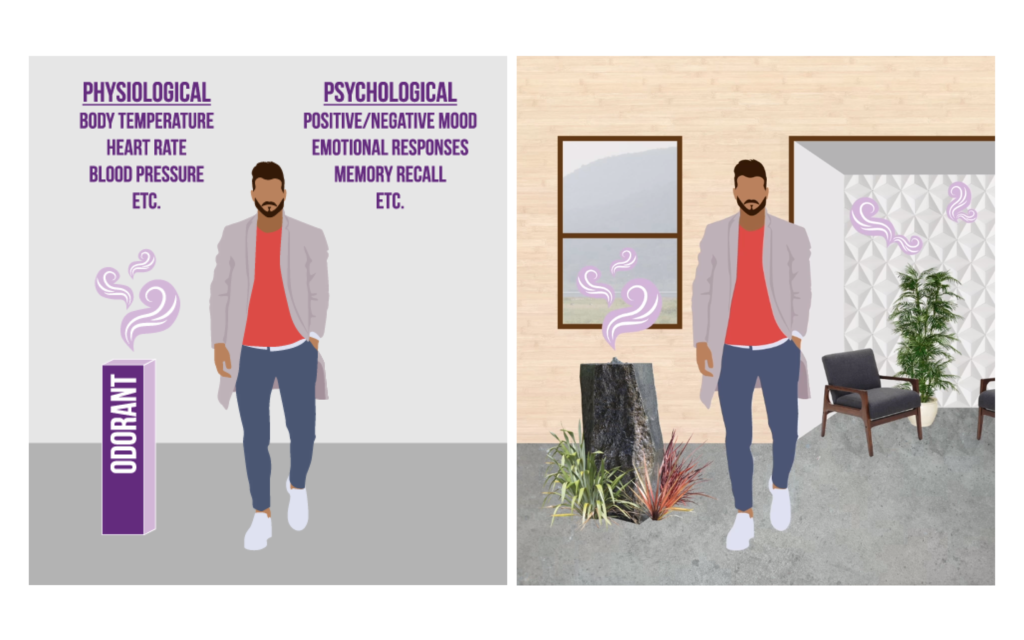

Engaging our sense of smell in the built environment holds tremendous potential to enhance occupant health and well-being. Olfactory experiences are known to prompt both physiological and psychological responses in people, allowing scents to influence emotions, behavior, and physical comfort. As we breathe through our nose, the air we inhale also contains chemical information from the odor molecules that trigger our sense of smell, known as olfaction (Yang and Pinto). As a result, the experience of breathing is intimately tied to the experience of smelling, and every breath we take engages us with our surroundings on a deep, sensory level. This makes the act of breathing more than just a biological necessity—it becomes a sensory experience. By thoughtfully integrating scent, architects and interior designers can craft environments that resonate on a deeper, more intuitive level, enriching the spatial experience and fostering a profound sense of connection to our surroundings.

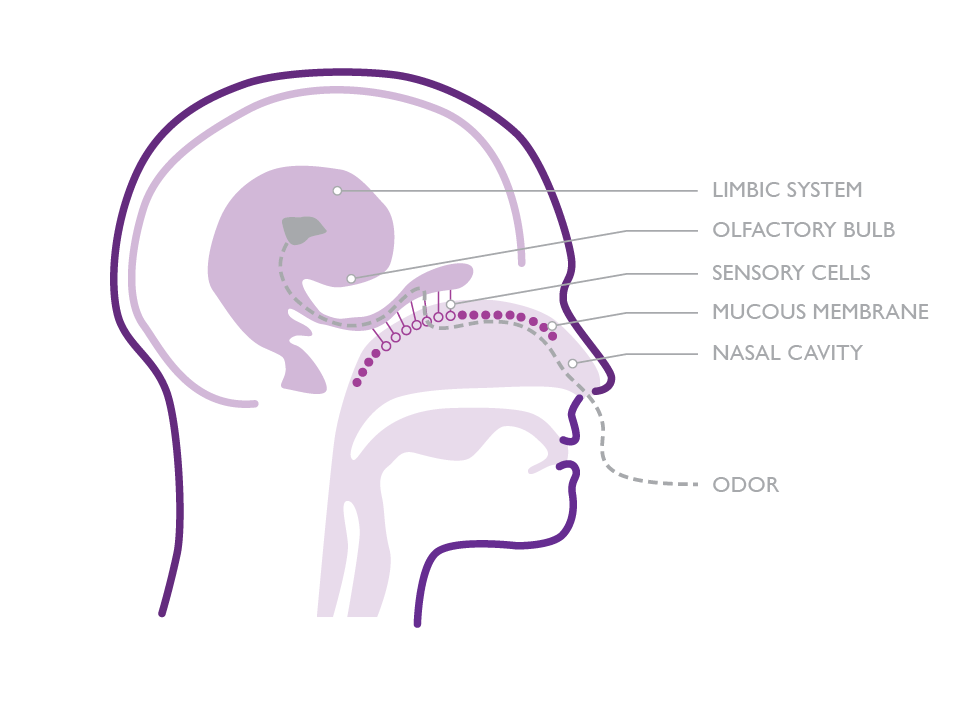

Odors are associated with memory and emotion. The parts of the human body involved in olfaction are known as the olfactory system. The biological structure and information processing of the olfactory system are unique from the other sensory systems. When we process information with our other senses, the neural information passes through the thalamus and onward to the cerebral cortex (Sullivan et al.), a part of the brain associated with higher-level processing and analysis. However, in olfaction, the “odor information is relayed directly to the limbic system, a brain region typically associated with memory and emotional processes. This neural organization provides olfaction with the unique and potent power to influence mood, acquisition of new information, and use of information in many different contexts including social interactions” (Sullivan et al.) [Figure 3]. Therefore, the fundamental biology of the olfactory system establishes a clear neural foundation for odor-emotional memory. As a result, a strong association between memory, emotion, and place can be developed through olfactory-stimulating environments.

We use our sense of smell to keep us safe. Our olfactory system is a vital tool for providing information about various elements in our environment. This ability to detect and process different odors is essential for survival, helping us identify food and water, sense the presence of others, and recognize potential dangers [Figure 4]. Some of our responses to odors are conscious or learned responses such as reacting to a life-threatening situation when one smells gas or smoke. Others operate below our conscious awareness, such as the influence of pheromones on attraction and social behavior (Yang and Pinto). Whether consciously or subconsciously, we rely on odors to navigate our surroundings and keep us out of harm’s way.

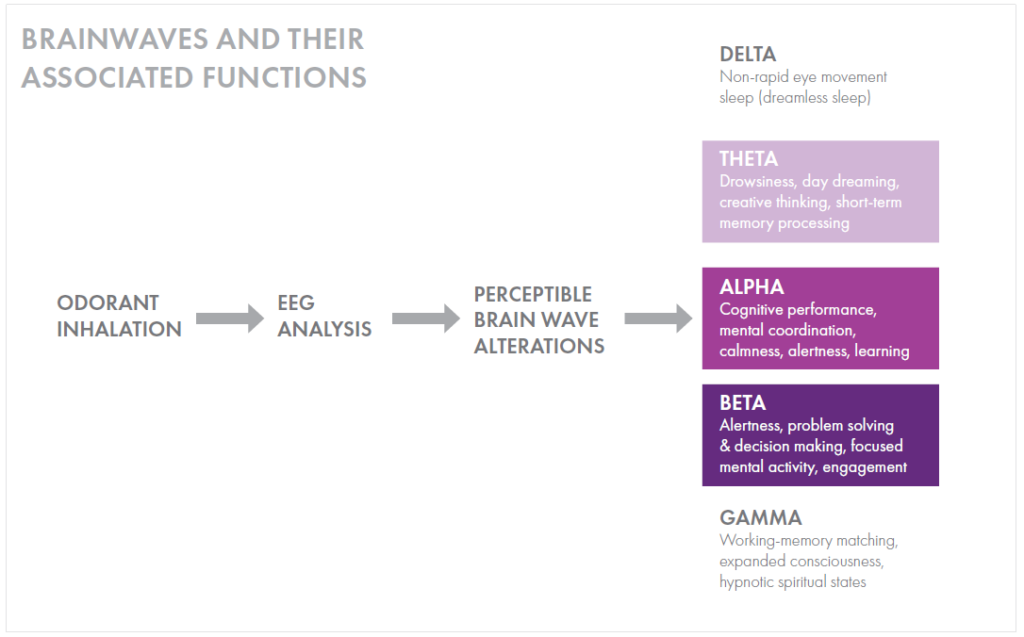

Olfactory testing has demonstrated that different odors produce specific patterns of neural activity. Aromachology, the study of how odors influence human behavior, is known to treat various psychological and physical conditions, from headaches and pain to insomnia, anxiety, depression, and digestive issues (Sowndhararajan and Kim). However, only recently have studies confirmed the neural effects of odors, revealing how olfactory stimulation influences the brain. Modern research substantiates that certain scents trigger psychophysiological responses by altering brain activity (Sowndhararajan and Kim; Diego et al.), which manifest in various brain waves. These distinct brain waves, known as Delta, Theta, Alpha, Beta, and Gamma, correspond to different states of brain function and can be measured by their frequency and location within the brain [Figure 5]. This evidence suggests that scents can directly affect our mental states, influencing alertness, relaxation, and even memory.

EXPLORING OLFACTORY DESIGN

Designing Scentscapes requires a thoughtful approach and re-framing our design thinking. To better understand how olfaction can be integrated into the built environment, precedent examples were collected from across the globe. To be included in the case study analysis, projects were required to meet the following criteria: 1.) The projects chosen had to be constructed and experienced by people during the project’s lifetime, thus ensuring they offered practical insights into olfactory design, and 2.) The projects must incorporate scent in a three-dimensional manner—therefore projects relying solely on HVAC systems to distribute odors were excluded.

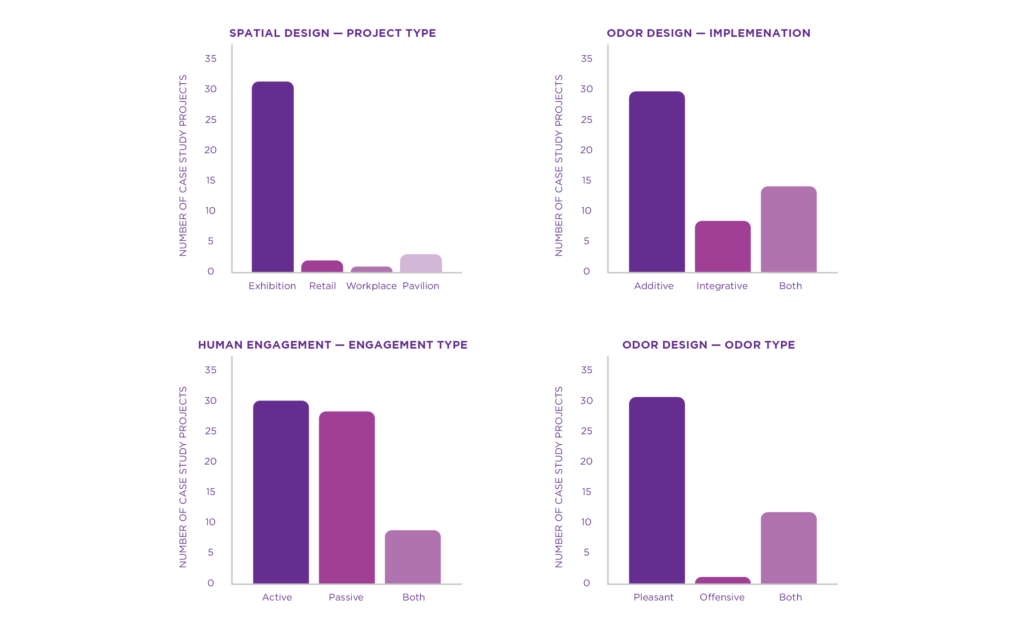

Over thirty-five constructed case study projects were selected and analyzed, including those from renowned architects Diller Scofidio Renfro, Peter Zumthor, and Rockwell Group [Figure 6]. The selected case studies represented a global range, covering five of the seven continents—North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia—as examples from Africa and Antarctica were not found that met the necessary criteria. The projects represented several building typologies, including retail spaces, exhibitions, and workplaces, offering a broad perspective on olfactory design.

The case study projects were reviewed and analyzed based on three principles—spatial design, odor design, and human engagement:

- Spatial Design:

Building typology, project lifespan, and odor delivery method were reviewed. Projects that had an expected lifespan of less than one year were considered temporary, and those greater than one year were considered permanent. The study evaluated how an odorant, the item responsible for emitting the odor, was designed into the built space. The odorants were defined as having a delivery method that was either additive or integrative. Additive elements were odorants that were not integral to the structure or finish materials but added to the space, such as objects, aerosols, or even bubbles. Integrative elements were odorants that are fundamental to architectural design structure or interior finishes, such as cedar wood paneling or the use of a clay and hay mixture to form a wall.

- Odor Design

The odorants included in the case study projects were analyzed in terms of quantity and quality. The quantity of odors was tabulated by the number of odors present in the project to create the sensory experience. The quality of the odors was defined as ‘Pleasant’ or ‘Offensive’ in each case study by following Dravnieks’ Hedonic Tones of Odors established in 1984, which rates various odor profiles on a scale of pleasant to unpleasant (Dravnieks et al.).

- Occupant Engagement

The case study projects were intentional about how the occupant would engage with the odorant in the space. This engagement was defined as either passive or active in the research. Passive engagement did not require the occupant to disturb or handle the odorant to release the odor/scent. Active engagement required the occupant to interact with the odorant to participate in the olfactory experience. The level of engagement characterizes the occupant’s experience in the Scentscape case studies.

Focusing on these principles in the case study analysis revealed several noteworthy patterns in the design of olfactory experiences [Figure 7]. The majority of the projects had a lifespan of less than one year, marking them as temporary structures, and mostly took the form of exhibits and art installations. These included exhibits such as ‘A Space for Being’ by Reddymade hosted by Google for Milan Design Week (2019), The ‘Chocolate Room’ by Edward Ruscha for the Venice Biennale (1970), and The Art of Scent – NYC by Diller Scofidio Renfro at the NYC Museum of Art and Design (2012). This indicates a trend towards ephemeral, curated olfactory experiences rather than permanent installations in the built environment.

The design strategies predominantly featured additive elements, where odors were introduced to the space in an applied fashion rather than integrated into the building’s materials or finishes. In instances where multiple odorants were employed, a quarter of these projects combined additive and integrative methods, illustrating a nuanced approach to olfactory design. A significant number of the case studies such as ‘Olfactory Path’ by Gwenn-Ael Lynn (2002) and ‘The Senses: Design Beyond Vision’ by Studio Joseph for the Cooper Hewitt Museum (2018) included more than one odorant, with a strong preference for pleasant scents. When unpleasant odors were present, they were usually balanced by more agreeable scents elsewhere in the space, enhancing overall sensory comfort.

Human engagement with odorants in the case studies was split between active and passive interactions, showcasing a range of methods for integrating olfactory experiences. These findings underscore the diverse approaches and considerations in designing olfactory environments and highlight a need to better understand how to create permanent olfactory experiences in the built environment.

DESIGN TRANSFORMATIVE SCENTSCAPES

The future of Scentscapes in architecture holds vast potential for enhancing occupant health and well-being by integrating olfactory design into the built environment. Unlike the case studies that mostly relied on temporary installations, architects and interior designers could explore how to embed Scentscapes into long-lasting buildings and spaces. By selecting materials that naturally emit desirable odors over time, such as specific types of wood or plants, or by designing systems that subtly diffuse scent through technology, buildings can maintain a consistent olfactory environment that evolves with the space and occupants.

Incorporating olfactory experiences into architecture could transform how we perceive and interact with our surroundings daily. By consciously tuning these experiences, architects and interior designers can create environments that not only respond to our sensory needs but also actively contribute to our mental and physical health. The longevity of such designs would require a deep understanding of how odors interact with both the environment and the human senses over extended periods, pushing the boundaries of traditional architectural practice into a new, sensory-rich dimension.

To integrate Scentscape design effectively, architects and designers need to consider the inherent properties of odors, the intricate human responses they trigger, and the spatial characteristics of the built environment [Figure 8]. Achieving harmony between these factors is crucial for creating spaces where scent seamlessly weaves into the architectural fabric, enhancing the sensory experience for occupants. For example, incorporating specific scents such as lavender or neroli, could regulate mood and enhance feelings of calmness in occupants, while scents known to promote alertness and improve cognitive function could increase occupant productivity. For highly specific programs, such as a doctor’s office, scents might be chosen to calm patients, whereas in a workplace, scents could be used to boost cognitive performance. In healthcare facilities, scents might support therapeutic outcomes, such as aiding memory recall in Alzheimer’s or dementia patients.

On the other hand, designing Scentscapes for spaces with diverse occupants, such as community centers, requires a more inclusive approach. This might involve creating olfactory wayfinding experiences, where different spaces are identifiable by distinct scents, aiding navigation and enhancing memory associations. Such designs offer non-visual sensory cues for visually impaired individuals, improving the equitable accessibility of architecture (Koutsoklenis and Papadopoulos). The interplay and distribution of various odorants with their unique olfactory characteristics would create a new method of wayfinding within the realm of architecture [Figure 9].

There is no universal approach to designing and implementing Scentscapes, as the experience of smell is subjective, and what works for one building type may not suit another. To create effective Scentscapes, architects and designers must thoughtfully consider various strategies that shape how scents are experienced within a space. The design strategies for the built environment include managing the three-dimensional scale of spaces, which influences the intensity and diffusion of odors, utilizing air movement to control scent distribution, selecting materials that naturally emit desired scents, and creating personalized experiences tailored to individual preferences.

- Three-dimensional Scale

The scale of an enclosed space significantly impacts the olfactory experience. In larger rooms, where the volume of air in the room is vast, odors become more diluted as they mix with the air. This reduces the concentration and perceived intensity of the odor. In contrast, smaller spaces concentrate the odor resulting in a more intense olfactory experience. By thoughtfully considering the spatial scale, designers can fine-tune the concentration and impact of scents. Expansive areas can accommodate multiple fragrances without becoming overpowering, while smaller settings can emphasize a more potent and distinctive olfactory presence. By manipulating the volumetric scale, designers can balance odor concentration and intensity, creating either subtle or memorable olfactory experiences.

- Odor Distribution and Airflow

Building ventilation and forced air systems are crucial in shaping the olfactory experience within a space, as air movement governs the distribution and diffusion of scents. Odor molecules generate plumes that drift with air currents, influencing how scents are perceived throughout the environment. Strategic ventilation can either achieve a harmonious scent distribution or concentrate odors in specific areas, thereby shaping the sensory impact of the space. By mastering the interaction between airflow and odor dispersion, designers can craft tranquil, evenly distributed Scentscapes or vibrant, dynamic olfactory experiences using various techniques. Understanding these principles allows for the precise manipulation of scent to enhance the overall spatial ambiance.

- Olfactory Material Selection

The selection of materials is another vital component in the design of Scentscapes as it provides integrated olfactory elements into the architectural fabric. Many organic materials, like certain types of wood, naturally emit scents that can enhance the sensory experience of the built environment. Walls made of organic materials, such as clay and hay mixtures or straw bales, create a sensory experience by selecting structural elements for their olfactory properties. Alternatively, using Hinoki wood in interior finishes or furnishings can introduce subtle, pleasant odors contributing to the overall atmosphere [Figure 10]. New products are also emerging in the building industry that offer innovative ways to integrate alternative odorants, such as scented wallpaper.

- Personalized Scent Experiences

Personalized olfactory experiences can be tailored to individual preferences, particularly in private or semi-private environments. This customization can be achieved through the strategic use of localized scent delivery systems, such as diffusers or scented objects, or by integrating advanced smart home technology. Smart homes could use computerized diffusers that enable occupants to select, adjust, and fine-tune scents. By offering hyper-personalized scent experiences, designers can create environments that not only resonate with the unique tastes of each occupant but also significantly enhance their well-being. This approach ensures that scent becomes a deeply personal and enriching component of the spatial experience, reflecting and adapting to individual preferences with elegance and precision.

THE FUTURE OF SENSORY DESIGN

Envisioning the future of Scentscapes reveals a transformative shift in architectural design, where scent becomes an integral element in shaping our interaction with spaces [Figure 11]. By recognizing the importance of olfactory experiences, we move toward a more inclusive and equitable sensory landscape—one that challenges the visual dominance long held in architecture that created a sensory hierarchy.

The future of Scentscapes is about crafting captivating, emotionally resonant, and cognitively engaging environments through the conscious use of scent. This holistic approach fosters spaces catering to diverse sensory needs, enhancing both accessibility and inclusivity. Imagine public spaces where scents guide those with visual impairments or workspaces where tailored fragrances enhance focus and well-being. Consider sensory-rich environments for children, designed to support their cognitive and emotional development through an immersive engagement of their senses. The future of Scentscapes lies in creating multisensory environments that deepen our connection to our surroundings and each other, fostering a more balanced and equitable sensory experience for all.

Bibliography

Blesser, Barry, and Linda-Ruth Salter. Spaces Speak, Are You Listening? Experiencing Aural Architecture. MIT Press, 2009.

Diego, Miguel A., et al. “Aromatherapy Positively Affects Mood, Eeg Patterns of Alertness and Math Computations.” International Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 96, no. 3–4, Jan. 1998, pp. 217–24. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3109/00207459808986469.

Dravnieks, Andrew, et al. “Hedonics of Odors and Odor Descriptors.” Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association, vol. 34, no. 7, July 1984, pp. 752–55. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/00022470.1984.10465810.

Grubb, M., and I. Thompson. “The Influence of Early Experience on the Development of Sensory Systems.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology, vol. 14, no. 4, Aug. 2004, pp. 503–12. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2004.06.006.

Johnson, Sara B., et al. “State of the Art Review: Poverty and the Developing Brain.” Pediatrics, vol. 137, no. 4, Apr. 2016, p. e20153075. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3075.

Koutsoklenis, Athanasios, and Konstantinos Papadopoulos. “Olfactory Cues Used for Wayfinding in Urban Environments by Individuals with Visual Impairments.” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, vol. 105, no. 10, Oct. 2011, pp. 692–702. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1110501015.

Lickliter, Robert. “The Integrated Development of Sensory Organization.” Clinics in Perinatology, vol. 38, no. 4, Dec. 2011, pp. 591–603. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2011.08.007.

Lipps, Andrea. “Scentscapes.” The Senses: Design Beyond Vision, Princeton Architectural Press, 2018, p. 224.

Lupton, Ellen, and Andrea Lipps. “Why Sensory Design?” The Senses: Design Beyond Vision, Princeton Architectural Press, 2018, p. 224.

Renner, Michael J., and Mark R. Rosenzweig. Enriched and Impoverished Environments. Springer New York, 1987. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4766-1.

Sowndhararajan, Kandhasamy, and Songmun Kim. “Influence of Fragrances on Human Psychophysiological Activity: With Special Reference to Human Electroencephalographic Response.” Scientia Pharmaceutica, vol. 84, no. 4, Nov. 2016, pp. 724–51. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm84040724.

Sullivan, Regina M., et al. “Olfactory Memory Networks: From Emotional Learning to Social Behaviors.” Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, vol. 9, Feb. 2015. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00036.

Yang, Jingpu, and Jayant M. Pinto. “The Epidemiology of Olfactory Disorders.” Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports, vol. 4, no. 2, May 2016, pp. 130–41. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-016-0120-6.