Historically, zoning and building codes have contributed to the concentration of low-income people of color into public housing developments that are physically and financially segregated from the public life of their surrounding neighborhoods. Today many public housing developments account for 20% of the highest crime areas in New York City, as a result of the systematic ghettoization of the low-income population. Toni Griffin describes concentrated poverty as one of three conditions of urban injustice that has not only created “spatial and social isolation” but has also had a “devastating impact on family structures, social networks, educational systems and access to economic opportunity1”. Griffin’s exploration of how the legacies of race structure and inform the built environment of American cities reveals the need for an urban alchemy. In essence, the reparation or re-construction of the codified and intentional ways that the urban landscape has been used to promote the subjugation of people based on their race.

The consequential visual impact on the public realm in these communities is evident in the degradation of urban quality. In a 2018 interview with Architects Newspaper Deborah Marton – Executive Director of the New York Restoration Project – describes the “Corbusian tower in the park” model of public housing as a “failed paradigm in its insistence that the green space be green poche”. In this model open spaces have remained a static and inactive form of urban dressing rendering them “unusable and inaccessible”. Marton defines the purpose of the fenced in green spaces as “not just about maintenance – but of control and policing”. Griffin and Marton reveal narratives embedded at different scales of American urban infrastructure and policy that sought to both segregate and engender an identity of invisibility for communities of color.

When posed with the question: “how can we improve architecture and “urban design through a human-centered approach?”, my immediate thought is to start with a community engaged process. In her book Resilience for All: Striving for Equity through Community-Driven Design, Barbara Brown Wilson writes that “community driven design – privileges community expertise over technical knowledge and resident capacity building over the design product”. Housing is an interesting place for exploring this topic because it lies at the intersection of life, work, and play but is also co-authored through a coordinated effort of architects, designers, policy makers, developers, bankers etc. The complexities of housing and the process within which it is developed is quite the opportunity to demonstrate the benefits of a human-centered design process in the creation of a built environment product. The methods of piloting, iteration and evaluation can be a fruitful approach to incremental change in addressing transformational change in the living conditions of marginalized communities.

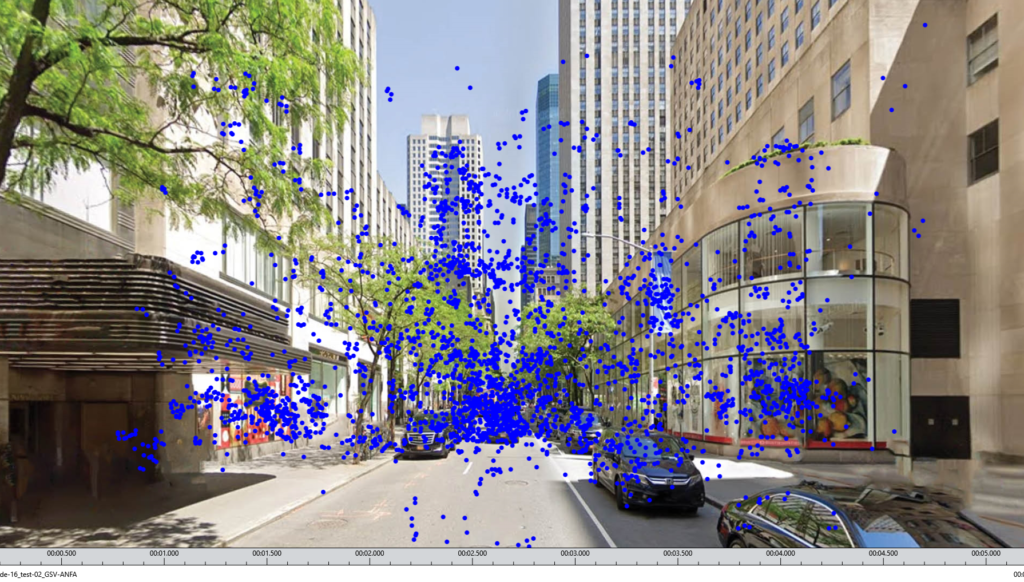

Over the past two years I have worked with a team of community organizers, planners, artists and other experts in government and non-profit sector to implement a citywide program striving to center the residents voice in the transformation of the conditions in public housing across New York City. The main question to frame our design challenge was how do you use design to address the social, economic and environmental challenges associated with crime? The journey to answering this question started with using an iterative process where residents are centered as experts and their capacity is developed to become human centered designers through a training program in Crime Prevention through Environmental Design, placemaking and community organizing. Success of the program has been defined by the premise that residents are leaders in defining the problem and brainstorming solutions in partnership with community-based organizations and government agencies.

As a result of this built environment initiative supported by a human centered design process there is a culture of self determination and agency that is being cultivated. Social networks are becoming more resilient and new partnerships are formed to co-create community safety. Each designed solution is uniquely tailored to addressing the challenges to community safety while instilling a sense of ownership. Through this process we have co-created new possibilities for transforming public open space with limited financial resources but an abundance of community will power.

Invest in dignity

Light the night

Expand activity on public property

Prioritize youth

Provide equity in maintenance

Enable social connections

Co-locate activities, community organizations and service providers

Start with what’s there

Images courtesy of the Center for Court Innovation and the NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are not the views of the NYC Mayors Office.

References

- Toni Griffin, Ariella Cohen and David Maddox, The Just City Essays: 26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity (J. Max Bond Center on Design for the Just City at the Spitzer School of Architecture at the City College of New York and the Nature of Cities, 2015, pg 12)