Abstract

This article analyzed the use of rapid ethnographic methodologies to assess community concerns for urban design practices. Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Process (REAP) is a compilation of methodologies that produce ethnographic knowledge in a short time frame and is constantly used for public health and sustainability. The article is about a participatory case-study conducted in the historic city center of Santiago de Los Caballeros, in the Dominican Republic. REAP was used to understand its application for urbanism. The case-study revealed a spectrum of cultures from different groups within the study area, and how the project would impact their ways of life. It also depicted a gap between the pre-existing proposals and the aims and challenges of the community groups.

If appropriately applied, REAP can produce valuable results, and help inform urban design practices while assuring that they are respectful to the populations they will influence.

Introduction

Since the Port Huron Manifesto, which gave a political voice to citizens in 1962, public participation has been increasingly been in public practices.1 In that same decade, participatory democracy leaked to urbanism and culminated in more activism for community engagement in urban practices.2 Today, almost every project – regardless of size and scale – includes built-in opportunities for community participation.

However, things are not as good as they seem. Participation usually lacks support from policy makers because of its high temporal, financial, and political costs.3 It can actually decrease participation and give an illusion of participation instead of a reality.4 The inefficiency of participation can arise from a lack of understanding of the community being designed for – their community structure, processes, practices, symbols, and values.5 In other words, current methods of ‘participatory’ design practices leave behind cultural aspects of communities.

The Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Process (REAP) offers a solution to bolster participation. In a short time frame, REAP collects cultural data and uses it to illuminate cultural values and identify community values and meanings. The methodology treats locals as part of the research team and allows for more full collaboration.6 Because of the limited time, one of the main aspects of the REAP is triangulation – the use of multiple methods – in a way that they complement or overlap each other, which maximizes the validity and reliability of data.7

This article investigates a case study, in which the author participated, that utilized REAP for urban design. The effect of a proposal to revitalize the city center and pedestrianize a central street in Santiago de Los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic was explored in this case study. The research reviews the different methods used in the case, how well they worked with one another, and how they helped to identify the cultures of community groups. The article concludes with some observations about the study’s usefulness for urbanist practices.

Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic

Santiago De Los Caballeros is the second-largest city in the Dominican Republic. From 2014 on, the federal government set the city as one of the main targeted industrial development areas of the country. To achieve nationwide development goals, the government drafted plans to address the main vulnerabilities of the city: climate change and sustainability risks, degraded and underutilized areas, pollution, and transportation.

From 2014 to 2018, the government worked in partnership with the International Development Bank (IDB) and created an Action Plan for the city which focused mostly on sustainability issues.8 That initiative was complemented by the City’s Strategic Plan of 2017-2030 which created policy frameworks to enable sustainable development, equity, participation, culture, and citizenship.9 The IDB’s plan aimed at mapping and analyzing the challenges the city faced in environmental terms.10 Following the prescriptions of the city’s strategic masterplan, the IDB’s proposals used a participatory design approach. They conducted four workshops with stakeholders to base their proposals. One of them was performed with youth living or working in the area, and three of them with experts in architecture, scholars, or city agencies.

The agency’s background research showed problems such as flood and climate change risks, spatial segregation, lack of urban infrastructure, safety issues, urban emptying, and abandonment of public assets. The public workshops showed a lack of security, parking spaces, green and recreation areas, nightlife, and housing.11 As a way to solve these problems, the IDB delineated three interventions: one park, one ecological corridor, and the city center. Each area then received a set of proposals that would help to improve the environmental and socio-economic conditions of the neighbourhoods. Proposals included improving urban infrastructure: increasing green areas and public spaces, increasing pedestrian access, restoring old infrastructure, creating affordable housing.12

The historic city center -which is relevant to this article- featured a collection of landmarked buildings, retail stores, informal vendors, and cultural institutions. IDB’s proposals navigated the revitalization of historic buildings, the provision of affordable housing, cultural uses, and pedestrian access. The IDB’s intervention, especially the proposals for pedestrianization of central streets, brought conflicts among local stakeholders. These conflicts led to an interruption in the project for further analysis.

Because of the complex nature of the project, a group of international students from Columbia University, overseen by professor Marcela Tovar, assisted in the investigation and proposals for the site. The group conducted onsite REAP for one week to formulate place and community-based strategies to reactivate the historic city center and understand why there was conflict among stakeholders.13

The methodology of Rapid Ethnographic Processes (REAP)

The REAP methodology design is based on the triangulation assumption. In this case, key stakeholder interviews, on-street interviews, transect walks, cultural mapping, asset mapping, and shadowing. The methods aimed to extract the community’s perspectives as much as possible while also understanding the institutional limitations. The researchers were divided into three subgroups, each one responsible for one or two methodologies.

One of the subgroups conducted interviews with city leaders from the cultural institutions, urbanism, landmarks, and small business departments. They were responsible for extracting the “official” view of the city – the one advocated by the government, as well as the policies and legislation in place.

Experts also participated in cultural mapping activities. This activity aimed to pursue a deeper understanding of people’s individual spatial and cognitive relationship with the environment and to represent their symbolic view of the city.14 Four individuals drew maps from memory and represented their personal view and local knowledge into the geospatial data, which was later analyzed and compared to other datasets.

At the community level, the researchers performed 48 semi-structured on-street interviews. Interviews took place on sidewalks, bus stops, green areas, restaurants, and retails. The goal of the interviews was to find out what meanings the city center held for community groups and what could be improved. There was no formal procedure for selecting interview subjects, but researchers tried to control factors such as gender, ethnicity, and race of interviewees.

The researchers performed transect walks with three local stakeholders. Transect walking involves walking through the site with a resident and asking them to relate the space with personal experiences. Walks took up to one hour and provided deeper information when compared to interviews. However, they were more difficult to organize, since participants had to commit for a longer period.

Researchers performed two other methodologies (shadowing and assets mapping). But because their results were built environment-related and not about cultural traits, they are not included in this research. All the gathered data was coded and analyzed for content by group and study.

Findings

The REAP produced findings that contrasted with the initial community engagement activities in the IDB proposals and showed a gap between the proposals and the community goals. It is worth noting that previous engagement activities consisted of four workshops and only one performed with community members.

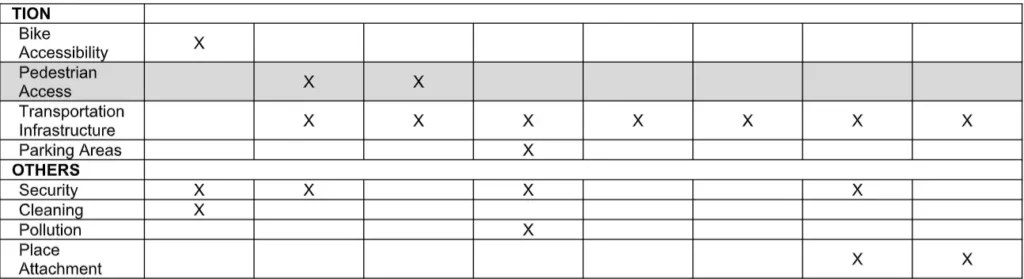

The table below shows a summary of the findings of each REAP engagement activity. The key points marked in grey were the ones adopted by the IDB’s plan.

When analyzing the results of each activity, we concluded that proposals arose from experts’ views and were not necessarily related to the community’s needs. Proposals to increase nightlife activities, which comprised of incentivizing restaurants in the city center, is a clear example of that and was introduced in the second workshop by experts and academics. However, it was clearly at odds with what the community’s experience was – they highlighted that they would not be able to use restaurants past working hours because of the lack of place attachment, security, and transportation difficulties. Although this measure could indeed create vibrant streets, as desired by the IDB’s plan,15 the community’s perception was that it would introduce a new cultural group into the city center – of those individuals who did not face transportation, access, or security challenges which would result in deep changes in the center communities.

The REAP divided stakeholders into two cultural groups: 1) experts, and 2) community groups, subdivided into women, men, and Haitian immigrants. Each group had its view and priorities for the revitalization of the city center.

Group 1: Experts

This group was consulted through cultural mapping and stakeholder interviews. Researchers did cultural mapping with two professors, a resiliency expert, and an expert on cultural institutions. Experts created complex maps, identifying details of landmarks, public policies, and proposals for the site. Some of them presented highly detailed maps, with drafts of architectural building elements, and the name of the owners of each landmark.

City agencies had mentioned measures to improve the city center through the pedestrianization of streets, revitalization of landmarked buildings, tactical urbanism, and incorporating street art. According to them, this would create a more livable and vibrant city center. Only one out of the 15 key stakeholders mentioned public participation. The analysis of the data gathered from this group showed a valuation of technical knowledge, especially architecture and urbanism when compared to other variables and a clear distancing from the cultural values each community group maintained.

Group 2: Community Groups

Researchers used three transect walks and 48 on-street interviews to reach this group. Data analysis showed the existence of three cultural subgroups: women, men, and Haitian immigrants.

Women:

The researchers found it difficult to reach out to this subgroup. Their presence in public spaces was limited. In two-thirds of the women’s interviews, a male figure interrupted the interview – generally the subjects husbands. To generate trust more trust a female researcher conducted all the interviews with this subgroup. Female vendors, especially street vendors, were more open to conversation. They represented 23 out of 25 of the interviewed women (five with street vendors, 18 with retail vendors).

Women highlighted that their main concern was security. Half of the female interviewees discussed the feeling of insecurity and suggested improvements on public lightning and police activities. One interviewee mentioned that “she asked for a permanent police car, but was never listened,” and added that she had been robbed more than once. Several women reported that they only felt secure when accompanied by a man and that when taking public transportation many mentioned difficulty in accessing it due to security issues and its irregular time tables. Most narratives related to security issues. Only one woman reported place attachment: a street vendor who said that she had been in the same place for more than one decade.

The transect walks were done uniquely with men. Although the researchers tried to keep a balance between gender and ethnicity, this was the only group open to performing the activity.

Men:

Men had the opposite perception of the city center compared to women. They were active users of public spaces and easily approachable. The researchers also had to shape the methodology to reach this group. On the first day, a female researcher conducted the interview, which caused a certain level of discomfort to most of the interviewees. They interrupted the interview to say that it was not safe for a woman to be unaccompanied. Afterwards, a male researcher joined the interview group.

Although the men shared security concerns, they said they had sometimes solved the matters by themselves– nothing that four out of 20 interviewees had guns, and two of them worked as private securities. For transect walks, researchers walked down the city center and discussed places of importance such as small businesses, street vendors, and public transportation routes. Again, few personal memories were attached to the site and the city center was not seen as a place of importance in their personal stories. One interviewee mentioned that he “spends four hours on public transportation per day” and added that his memories were attached to the outskirts of the city where he lived and spent his free time. Another person added that “the city center is not for me” and that he did not feel belonging nor believed that the urban aspects of the site were built for them.

Haitian Immigrants:

The third identified subgroup were Haitian immigrants, which was the most difficult group to consult. Only three men were interviewed. One of them was a street vendor, and the others were lined up near a government building. Because of their vulnerable situation (some of them were undocumented or refugees) they were not open to speaking with the researches freely; they provided no or only mirrored responses during interviews. For example, when asked about street improvements, they remained silent, and would only answer when someone provided an example.

Although no significant data could be gathered from this specific group, they comprise a unique cultural group that should receive special attention in the redesign of the city center.

Conclusions

This case study showed an example of how ethnographic information can be quickly gathered and used to inform design and urbanism measures. In this specific case, a segregation was shown between the public policies developed by experts and the community they were working to serve. While experts highlighted architectural features, landmarks, and land use, community members showed different perspectives and priorities for the city center. Women’s narratives showed their pressing security concerns in public spaces, men’s interviews showed their disconnection and lack of place attachment, and Haitian immigrants clearly expressed disempowerment. No group – with the exception of one expert – showed signs of place attachment.

This analysis showed that the existing proposals for the city center were not based on the community’s needs. Although the original plan had intended to heavily include community participation. In practice, the proposals had actually overlooked the community’s needs and had been perceived as if they would result in extreme cultural changes in the urban environment, such as introducing unwelcomed new users.

In conclusion, REAP produced in-depth and relevant culturally-based data. REAP could be the first step towards actual pragmatic, participatory urban design. REAP could help strategize participatory measures for design and urbanism processes that consider cultural and communities’ values and respect them instead of giving the facade of participation.

References

1 Istenič, S. P., & Kozina, J. (2019). Participatory Planning in a Post-socialist Urban Context: Experience from Five Cities in Central and Eastern Europe. Participatory Research and Planning in Practice The Urban Book Series, 31-50. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-28014-7_3

2 Laskey, A. B., & Nicholls, W. (2020). Jumping Off the Ladder. Learning from Arnstein’s Ladder, 203-227. doi:10.4324/9780429290091-18

3 Maginn, P. J. (2007). Towards more effective community participation in urban regeneration: The potential of collaborative planning and applied ethnography. Qualitative Research, 7(1), 25-43. doi:10.1177/1468794106068020

4 Arnstein, S. (2020). “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” The City Reader, 290-302. doi:10.4324/9780429261732-36. Hillier, J. (2003). `Agonizing Over Consensus: Why Habermasian Ideals cannot be `Real. Planning Theory, 2(1), 37-59. doi:10.1177/1473095203002001005

5 Handwerker, W. P. (2001). Quick ethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. Maginn, P. J. (2007). Towards more effective community participation in urban regeneration: The potential of collaborative planning and applied ethnography. Qualitative Research, 7(1), 25-43. doi:10.1177/1468794106068020

6 6 Taplin, D. H., Scheld, S., & Low, S. M. (2002). Rapid Ethnographic Assessment in Urban Parks: A Case Study of Independence National Historical Park. Human Organization, 61(1), 80-93. doi:10.17730/humo.61.1.6ayvl8t0aekf8vmy

7 Handwerker, W. P. (2001). Quick ethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. Taplin, D. H., Scheld, S., & Low, S. M. (2002). Rapid Ethnographic Assessment in Urban Parks: A Case Study of Independence National Historical Park. Human Organization, 61(1), 80-93. doi:10.17730/humo.61.1.6ayvl8t0aekf8vmy

8 International Development Bank (2018). Vive el Yaque. Recuperación Urbano Ambiental del Rio Yaque, Santiago de los Caballeros. Washington, DC.

9 Plan municipal de ordenamiento territorial de Santiago, PMOT-Santiago 2017-2030, 3240-19 (2019).

10 International Development Bank. (n.d.). Ciudad Sostenible. Retrieved from http://santiagosostenible.do/santiago- ciudad- sostenible/

11 International Development Bank (2018). Vive el Yaque. Recuperación Urbano Ambiental del Rio Yaque, Santiago de los Caballeros. Washington, DC.

12 International Development Bank (2018). Vive el Yaque. Recuperacion Urbano Ambiental del Rio Yaque, Santiago de los Caballeros. Washington, DC.

13 13 Almonte, E., Calvesbert, T., Claramunt, P., Estefam, A., Gonzalez, A., Kang, E., Yang (2018). Practicum on Santiago de Los Caballeros. Columbia University, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation.

14 Fraser, D. S., Jay, T., O’Neill, E., & Penn, A. (2013). My neighbourhood: Studying perceptions of urban space and neighbourhood with moblogging. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 9(5), 722-737. doi:10.1016/j.pmcj.2012.07.002. Viveros de iniciativas ciudadanas (2017). Cómo hacer un mapeo colectivo. Madrid: Continta Me Tienes. Ollivierre, A., Ramlal, B. (2015). Participatory Mapping: Caribbean Small Island Developing States, Forum on the Future of the Caribbean. St. Augustine: University of the West Indies, Doi: 0.13140/RG.2.1.1112.0165

15 International Development Bank (2018). Vive el Yaque. Recuperación Urbano Ambiental del Rio Yaque, Santiago de los Caballeros. Washington, DC.