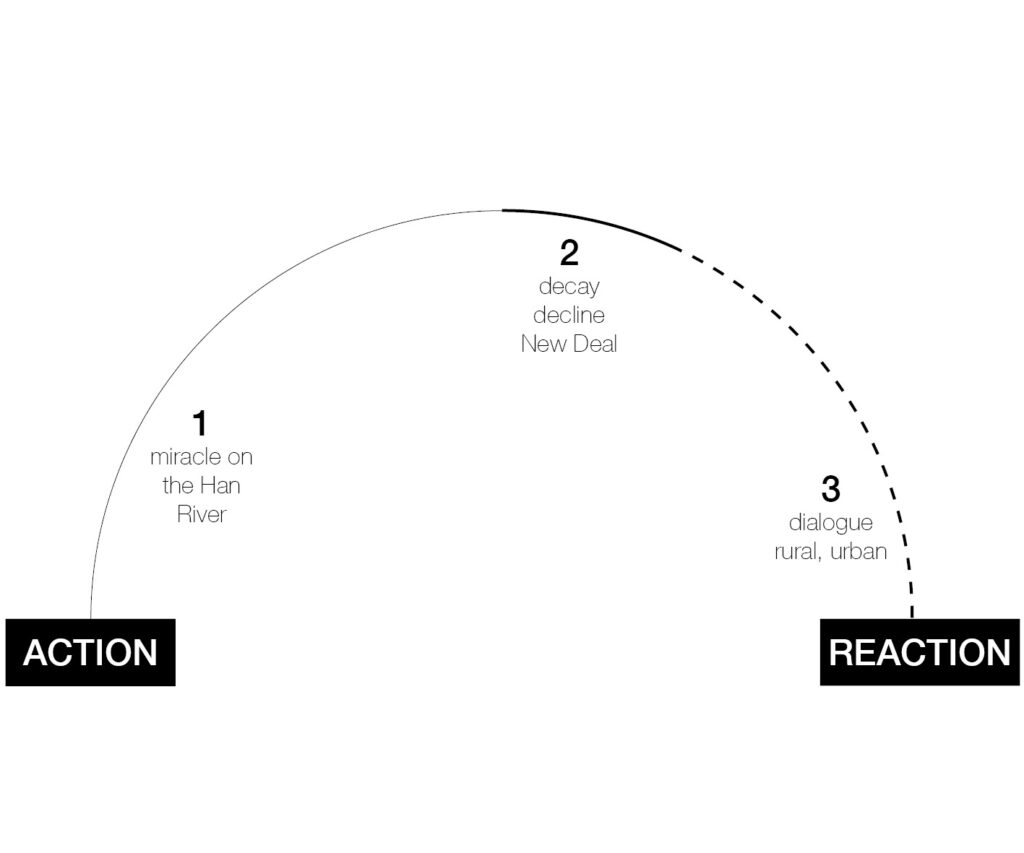

“Every action has an equal and opposite reaction” – Isaac Newton

Miracle on the Han River

There is no dearth of statistics that constantly remind us that the world has been on an urbanisation drive in the last century. This is especially true of Asian countries where this drive has accelerated over the last decades. South Korea’s Miracle On the Han River is the epitome of rapid industrial and economic growth. A civilization that has been in existence for the past 5000 years rose to become the fourth largest economy in Asia in just 50 years.

The Decay of the Miracle

It is natural that this accelerated action receives an equal and opposite reaction. Urban decay has long been a subject of concern in South Korea. Development in the country has been Seoul-centric since independence in 1947. Today, 48.2%1 of the national population live in the Seoul Capital Area.

The effects of this are two-fold. Within Seoul, urban growth was rapid to accommodate for the rapid influx of population, often leading to a substandard quality of construction and infrastructure. Old parts of the city were left to decay as newer ones were built. Outside Seoul, development was slower. Small and medium sized cities which saw an initial growth spurt halted soon after because of the magnetic attraction of Seoul.

For example, Cheonan — a medium-sized city in the province of Chungcheongnam-do initially faced pronounced growth but is now earmarked as a site of urban decay. Like many other cities, Cheonan has new high-rise developments, often the mark of ‘growth’ against a backdrop of an abandoned old, low-rise neighbourhood. The occupancy rate in the high-rise apartments is low despite it being the preferred housing type in Korea. Urban decay in small and medium-sized cities in Korea is characterised by increasing out-migration, an ageing population, vacant or abandoned buildings and declining business and local commerce rates.

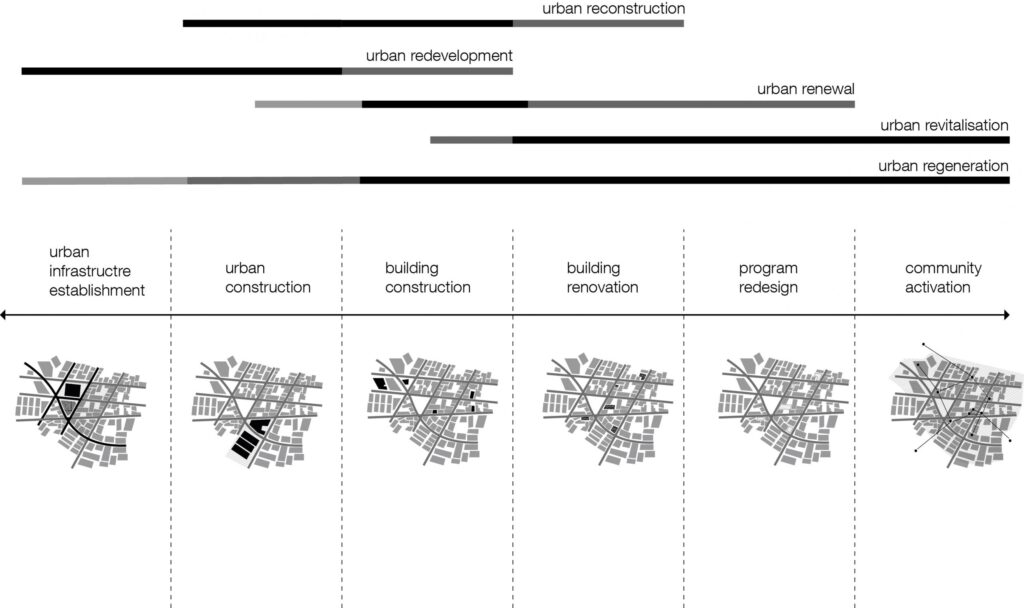

Reconstruction, renewal, redevelopment, regeneration and revitalisation

Response to decay in cities has adopted new definitions over time but has always remained a “re-something”. Terms like reconstruction, renewal, redevelopment, regeneration and revitalisation are part of the urban vocabulary and are often used interchangeably. Dictionary definitions of the terms attempt to make this differentiation but case studies and examples prove that they are used interchangeably because urban projects often include interventions from more than just one category. The term ‘ urban regeneration’ is often used in Korea because it encompasses all the ways to tackle urban decay.

New Deal

The new president Moon Jae-In and his government’s stated intention2 of renouncing the tabula rasa approach to cities has led the country to rethink urban obsolescence, decay, and shrinkage. These factors are now integral to the selection process for the New Deal Urban Regeneration Program, introduced in 2016, which aims to make cities more ‘socio-centric’. The change in discourse from urban development to regeneration has created a space for the inclusion of one important element that had been missing from the whole reconstruction, redevelopment, renewal process i.e the inclusion of end users and citizens in the decision-making process.

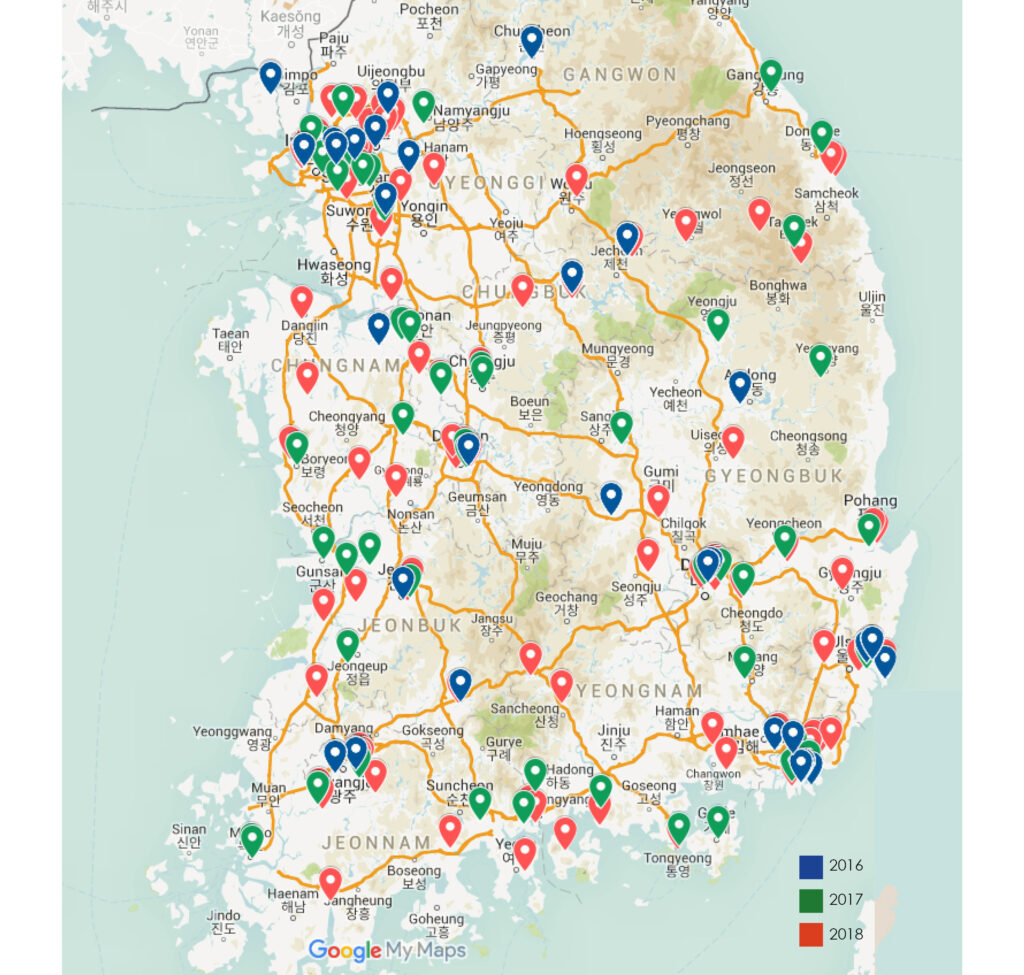

Even though there had been a rise in citizen involvement in projects in the last decade, it is in the past three years that it has gained traction. The program has undoubtedly caught the attention of the post-industrial labour force – creatives like architects, designers and urbanists. New Deal projects are exclusively designated outside of Seoul in order to provide a balanced and ‘just’ approach to urban revitalisation in the country. Recently the term has been extended to projects in Seoul but they fall under the local government’s scope and budget.

In 2016, 31 projects across the country were earmarked for the first New Deal projects. That this number more than doubled to 67 in 2017 and 100 in 2018 demonstrates the government’s will to tackle the urban decay across the country. New Deal projects are classified into five categories — Housing Renovation, Neighbourhood Renewal, Neighbourhood Activation, Core City Renewal and Economic Renewal. Community activation, involvement and integration in the planning process are a requirement for New Deal projects, which is what sets the policy apart.

These projects need to necessarily set up a local, ‘site support’ office within the neighbourhood where the interventions are to be proposed. This is to ensure that the locals and the project officers can communicate directly with each other. The framework for New Deal projects ensures that the government can only buy up to 30% of the land within the project site, allowing local land owners to come forward and either follow the example set by the government or propose their own ways of building value to their property. Another requirement is to set up an ‘urban regeneration school’ that aims not only to educate the locals with the different ways in which their neighbourhood can be vitalised but also to equip them with the tools to carry out the same. There are a number of community meetings to be held every month. A local activation team is imperative to carry the project forward for a period of five years. Within this framework, 198 projects have been under execution for the last 3 years.

De(ep) Growth

De(ep) growth, a take on degrowth, distributes the right to urban space across a spectrum of diverse actors. For the last two years we3 have tried to navigate the balance between powerful actors, such as the government and developers, and those who have traditionally been excluded from the city-making process: the citizens and users and the targeted audience of the regeneration program.

We illustrate our experiments with deep growth through two projects: one in Cheonan, as a part of the New Deal Program and one in Dobong in the periphery of metropolitan Seoul, as a part of Seoul’s urban revitalisation program which is now in the process of getting funds for Seoul’s New Deal Program4.

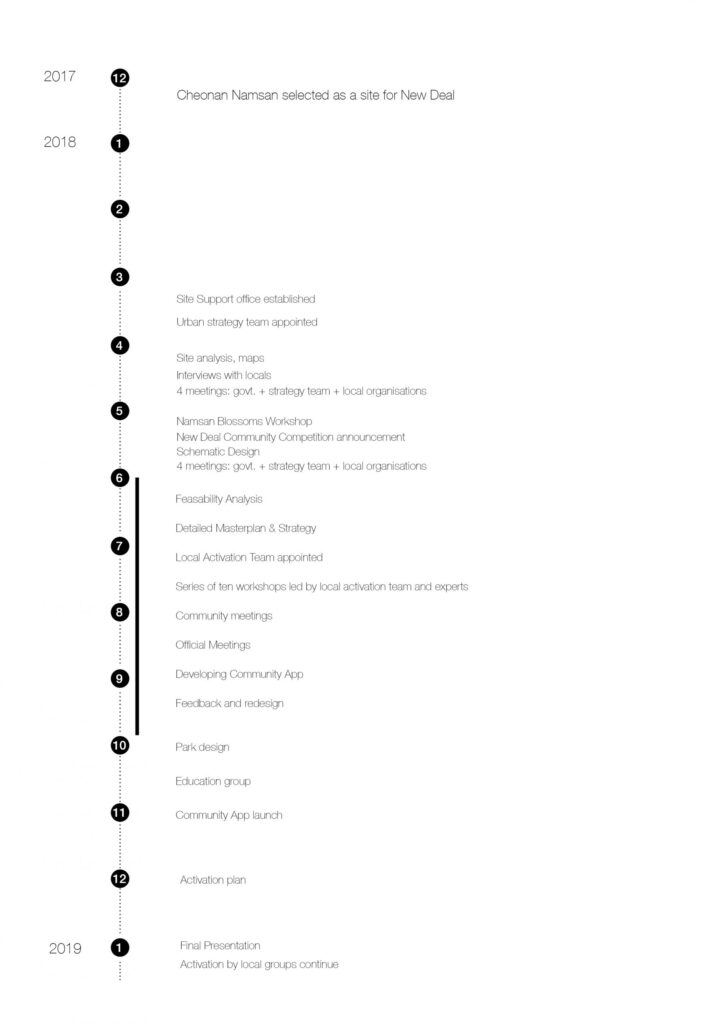

Urban Regeneration in Cheonan-Namsan

Cheonan is a medium sized city in the Chungcheongnam-do Province with a population of approximately 650,000 residents. Cheonan is strategically located in the peninsula and is a major transportation hub between Seoul and the southern cities like Busan and Daegu. The city began expanding in size in the late 1960s and was one city other than Seoul that saw increasing development for the latter half of the 20th century.

While this growth was taking place in newer city fringes, in many older neighbourhoods, there was a rising number of decaying building stock, declining commerce and a decrease in population. These conditions earmarked some sites in Cheonan for the New Deal Program. Under the categories Neighbourhood Regeneration, we won the commission to develop a strategy for the urban regeneration of the Cheonan neighbourhood.

The Cheonan-Namsan is a low-rise neighbourhood surrounding the Namsan, a hillock named after the famous Namsan hill in Seoul. The Cheonan-Jungang market lies at the base of the hillock and acts as the primary commercial node of the neighbourhood. At first glance, it was easy to identify the problems with the physical fabric — The streets were too narrow. A railway line ran along the fringe of the neighbourhood where the stock was mostly vacant or dilapidated.

To approach how to strategize for this declining neighbourhood, we proposed a workshop, Namsan Blossoms, in May 2018 to invite local residents to interact with local experts and skilled professionals to identify areas of potential. Over the course of four days, local residents, government officials, university students, youth from neighbouring areas, skilled experts and professionals went around the neighbourhood and brought to light the different ways that the neighbourhood could be improved. The purpose of the workshop was to simply kickstart the project and announce to all interested actors that it was open for discussion. The workshop also helped identify actors from the locality who were willing to participate in the project.

Over the next months, vacant houses in the neighbourhood were mapped and then overlaid with land ownership drawings to identify which buildings could be used for interventions immediately and which ones would need permission from the owners. A masterplan was then made to address the ideas that arose at the workshop.

In order to ensure continued engagement with the interested actors from the workshop, the masterplan was presented at a local meeting. A community activation group was formed involving some of the local youth to implement intermediate strategies of the masterplan. We then organised a series of ten mini-workshops with the community activation group to create a sense of local ownership over the masterplan.

One of the buildings by the base of the Namsan temporarily took on the role of a community center for this purpose. Over the course of ten weeks, the locals participated in helping convert vacant plots of land into farming sites where they planted cabbage to be harvested late in the year to make kimchi for the community. Talks, lectures, farm visits and feedback sessions followed. Keeping in line with a mobile-based community, an application where locals could post their grievances, publicise events and receive notifications about the project’s progress and events was created.

While the strategy stage of the project ended in early 2019, all New Deal projects are locally carried on for five years. At Cheonan, the local youth and the program officials continue to engage the locals in urban activities while the buildings and areas marked for redevelopment are being contracted to architects, engineers and other professionals.

Community Activation in Dobong-2-dong

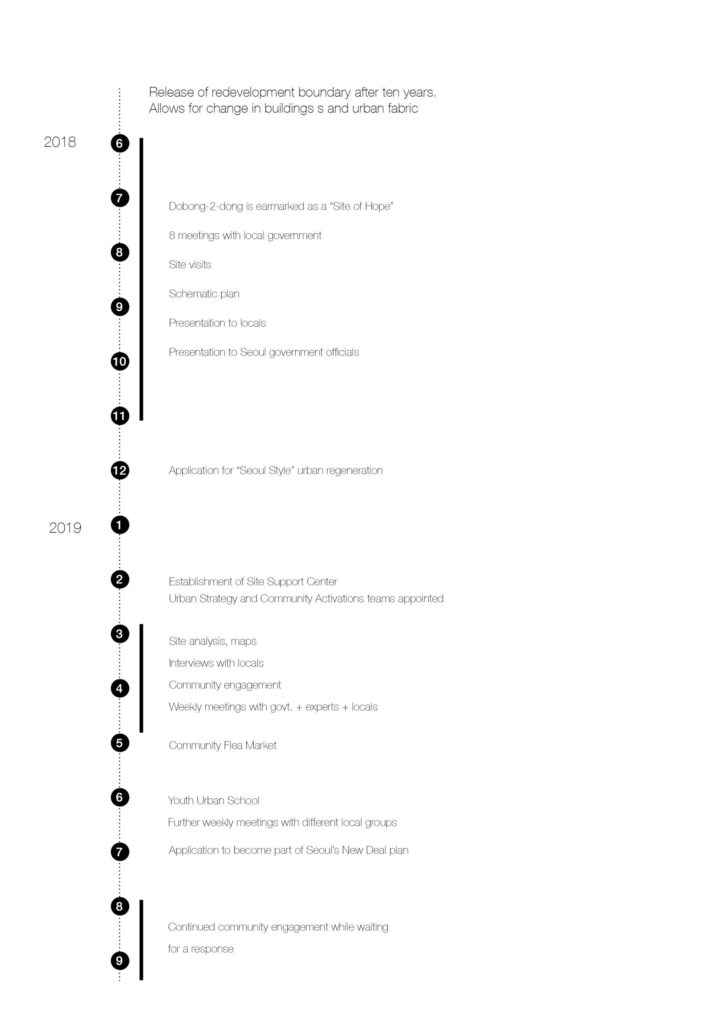

Dobong-2-dong is an area in the northern periphery of Seoul that was originally earmarked for a redevelopment project. In typical fashion, developers and real estate tycoons were supposed to build apartment blocks and other high-rise amenities but the site failed as a profitable venture. Once the urban development status was removed from the area, it seemed to suffer even more— its residents were disheartened that their area was deemed not enough value for bigger projects. The site was then marked for urban regeneration to activate areas of interest by involving the local community in the process.

Dobong-2-dong is characterised by low-lying houses, an ageing population and small businesses that have moved to the area because of its cheap rent. Working with the community, we made a master plan strategy for the neighbourhood based on which the local office applied for the site to become a New Deal Site in Seoul.

After successfully receiving the status as a site for Urban Regeneration in Seoul, we were appointed as the community activation team for the project. The first local urban regeneration office was set up in February 2019. Over the course of the next months, countless interviews with the locals revealed their hesitations towards living in the neighbourhood. Events like local flea markets fostered better communications amongst the locals and with the project officials. An urban regeneration school with the local youth allows for a better connection with their neighbourhood in the hope that they will bring more business into the area in the future.

In parallel, another team worked on the regeneration strategy, identifying areas of opportunity that could be converted into sites of attraction or interest for those within and outside of Dobong-gu.

Dobong-2-dong’s newly gained status as a Seoul New Deal site is an important step in ensuring that the neighbourhood isn’t entirely abandoned in the coming years, and might set the example for other such neighbourhoods in Seoul.

The Challenges in the Process

The framework set out for the New Deal Program, theoretically, should achieve its objectives of urban regeneration. It has been able to shift the narrative from a build anew approach to a softer, community-oriented approach. However, practical manifestation of the framework comes with its challenges. Since the approach is new in South Korea, project proponents often have to experiment with methods.

For example, in Cheonan, the idea of a large workshop to kickstart the whole process was one that was met with a certain resistance. Workshops are a common tool in urban activities in other parts of the world but it is still to gain traction in Korea. One of our biggest challenges was to convince not only the government officials but also the local residents and other experts that a free-flowing format could work in this context. It was after a lot of back-and-forth conversations that Namsan Blossoms, the workshop for Cheonan, took place. Thankfully, doubts about the workshop disappeared after people experienced it first-hand and could then see the value in holding such an event. The follow-up series of workshops were led mainly by the local activation team.

In reality, the biggest question that remains is one of stakeholder participation: how can one engage a community that might not want to be involved? As a society, we are used to evaluating projects in quantitative terms. Number of housing units created, economic turnover, number of jobs created, etc. are all parameters that are typically telling of a neighbourhood’s vitality. It is difficult to do the same for a softer approach. How is one to measure community engagement or a local’s incremental involvement with an urban regeneration project other than in terms of number of interviews? In Dobong-gu, active local groups initially felt threatened by the sudden presence of an urban regeneration office. Their suspicion is understandable seeing that the New Deal is a new program in its nascent stages, the results of which will take at least five years to be published publicly. As a result, we were in a position where it often felt like community activation was almost a forced experiment on the neighbourhood. Decidedly, time has allowed for the locals to develop a relationship with the urban regeneration center and now sees increased activity. But it is still a challenge to find the right balance between executing ideas within the New Deal framework, the public’s wishes and our own ideals for a ‘good’ urban project.

Even though we are strong advocates of the multidisciplinary approach to urban projects, it is evident that there needs to be a strong communication between all project proponents and an openness to a trial-and-error approach. It is only through experiments that we can find a practical framework for New Deal projects.

One of the requirements of the New Deal projects is to have a local activation team that keeps the project alive in the area for a period of five years. While 5 is an arbitrary number, the recognition that urban projects need to develop incrementally over time as opposed to the previous generation’s ‘build quickly’ approach in itself is a step-forward for urban dialogue in South Korea. It allows for a deeper growth – one that could be measured quantitatively once that stipulated project period comes to an end, but also one that has undoubtedly contributed to an improved quality of urban Korean life.

References

Notes

- As published by KOSTAT – Korean Statistics

- 100 Policy Tasks Five-year Plan of the Moon Jae-in Administration 2017

- The authors of this article are part of of Yangji, an urban planning, design and research office that works primarily on urban regeneration projects across South Korea. The article is a product of their research and first-hand experience working on New Deal projects.

- While New Deal programs fall under the scope of the Central Government, Seoul has recently launched its own New Deal program that falls within the scope of the local government.

* All figures produced by the author.