Design thinking, or ‘human-centred design’ is a problem-solving approach that empowers individuals or teams to deliver products, services and experiences that address the core needs of final recipients.1 Multiple fields use this method to create iterations and tackle even social issues. Focus on human experience allows designers, architects, builders and relevant authorities, to design responsively built environments.

The City of Sydney Council (COS) identified the need to include a library in the Green Square Town Centre (GSTC) in their Social Plan 2010.2 Their Library Network Strategy assessed the need for about 6000 sqm of library space by 2012 as the number of visitors to the state’s public libraries were rising significantly.3

To ensure they delivered a high-quality intervention, the council announced a two-stage, open-call international design competition. An early consultation with the local community helped to understand their expectations from the new Library and Plaza. They wanted the plaza to be capable of accommodating public events and markets. Rather than formal community buildings, residents considered open spaces as significant locations for social interactions. They expressed the need for a place to gather, linger and dine, an outdoor space with shade and shelter as well as spots to enjoy the sunlight. Considering their needs, the competition brief specified the aim to create an ‘urban living room’ at the heart of the urban renewal area.4

Libraries in the 19th century were vast institutional buildings with monumental grandeur. Libraries in metropolitan cities today emphasise on proximity to the public and other less formal spaces.5 The Green Square Library and Plaza – designed by Studio Hollenstein in association with Stewart Architecture – has won several prestigious awards. It represents a contemporary library that addresses the current needs and future aspirations of people.

The exploration of libraries as a building type was central to their proposal. The role of a library has evolved from a place of information to a hub for community activities. With rapid changes in technology, people’s ability to access information has changed but the library exists as a physical source of knowledge and a multifunctional space that broadens the scope of learning through digital and physical interactions.

Recognising the need to address this evolution, the winning team deinstitutionalized the library building through their design and interlinked it with a plaza, preserving open space for future generations.6 Judged against libraries across the globe since 2013, the project was awarded the Architectural Review Library Award 2018.

The Winning Entry

Considering the given site would soon be surrounded by residential towers, the winning team deemed that the ‘most valuable commodity’ that can be provided to the public was ‘space’.7 A space that was open, communal, inclusive, and free to use all day. This challenged the typical library design by putting forth a strong argument for burying a large portion of the building underground and placing the plaza above it to maximise public open space.8

Architectural elements are deliberately arranged loosely across the plaza to eliminate strict boundaries between multiple uses. The design encourages the evolution of a library from a place for books to a civic space that can host other community activities.

This loose arrangement continues across the plaza and into the library itself. Unlike conventional libraries, this project has multiple entries and offers interior views from different levels. The triangular entry pavilion and tower read as external volumes piercing through the plaza. The amphitheatre and the sunken garden read as punctures or open volumes for the library underground. ‘The overall effect is urban – it doesn’t offer the experience of being in a single building.”9

The fragmented design allowed access to parts of the building without keeping the entire library open – the tower had keypad access so that it could function at night. 42 Light wells on the plaza provide natural light into the library space below. With community input, architects experimented with the light wells by reducing their number, changing them into long slits and even raising them to form benches for the Plaza. Alternate skylights were also considered, but in the end, 39 of the light wells were retained with their originally proposed frosted glass.

Although the competition brief described the plaza as a foreground feature for the library, the inclusion of the two components within a single design commission allowed the architects to treat it as a space-making exercise; both the plaza and library – though made of loosely arranged parts – flowed into and contributed to each other’s spatial experience. Meaning, that in the library design, the plaza was just as important as the library building.10 This furthers the original project emphasis on the design of a multipurpose, civic space.

The locals “took ownership of the building within hours of its opening,” meaning that the response to the Library and Plaza made it project a “relevant blueprint for community buildings in new precincts with similar densities,” and highlighted the success of the design process in engaging its community members.11

Involving the Community

A list of key stakeholders was included in the Green Square Communications, Engagement Strategy and Action Plan 2012 to ensure the active participation of all internal and external stakeholders. From the project inception to the final design and early activation phases, the Action Plan indicated the commitment of the council to consult the public at different stages of the project.

Of the 167 submissions received, the jury anonymously shortlisted 5 entries which were revealed to the local community at the inaugural Community Fair at Tote Building. Residents got the opportunity to see and make comments about the potential buildings. The entries were also available on SydneyYourSay online portal for the wider community to provide inputs. Taking public views into consideration, the jury suggested a winner and COS hosted a Design Excellence Forum where architecture enthusiasts gained an insight into why this underground design was the most appropriate for Green Square.

Concept Refinement Stage

Green square residents/representatives, Students and Youth groups, Chinese community representatives and Library staff members, (in regards to the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) spectrum) were brought in to consult.

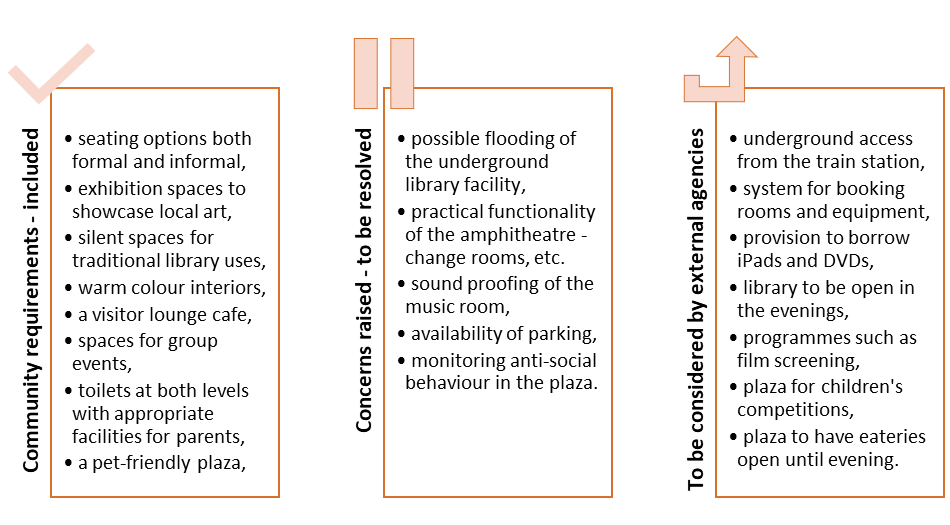

Focused feedback was effectively sought through targeted workshops with different user groups.12 Owing to the broad interest in this project, the public was able to provide feedback at the ‘SydneyYourSay’ portal. Schematic floor plans were made available and an online discussion forum was set up, attracting about 1400 viewers. A subsequent report on the key outcomes was also made available for the participants.

The objectives hoped to be gained by the community’s feedback and the workshops were to:

- Inform the community of the jury’s decision and to explain the winning proposal’s relationship to the other projects in the GSTC.

- Reflect about how the proposal addressed the key criteria recommended by the community during earlier consultation.

- Highlight the architect’s enthusiasm for an open design process by ensuring community involvement at project milestones.

- Test ‘design assumptions’ and understand the community’s perception of the project’s proposed indoor and outdoor spaces.

- Involve a broad range of user groups who would potentially use the premises.

The design team was able to address or at least consider most of the feedback provided by the community. The involvement of architects in the consultation sessions provided them the opportunity to directly hear from the community13, thereby decreasing the chances to hamper data collected during the consultation process.

Stakeholder Consultation at Development Application Stage

Post-concept stage, the council established the need to amend existing planning and development controls. The built form of the winning proposal was substantially different from what was originally envisaged for the site in the GSTC Local Environmental Plan 2013 (LEP).14 The LEP and Development Control Plan (DCP) are frameworks – land use and development controls of a particular site are indicated here. However, a proposal can be slightly inconsistent with these controls and may need the council to make amendments.

In this case, the library building was imagined (in the LEP) to be a large structure above ground. The winning proposal placed most of the building underground and so required the council to make minor changes to height restrictions and other access routes. However, the proposed design offered better public amenity because it overshadowed the open plaza less. This gave rise to a Draft Planning Proposal which justified to the stakeholders the need to amend current controls. The proposal, along with the draft amendment to the LEP and DCP, were placed on public exhibition for 28 days.15

Exhibition materials were made available for public at the Green Square Library, customer service centres in the suburb and on the Council website. 300 landowners were sent notification letters and an invitation was advertised in a local newspaper. These proposed amendments to the LEP and DCP were required to facilitate the execution of the winning design:

- the LEP to allow a maximum Roof Level of 46m instead of the 44.5m restriction. This allowed the seven-floor tower to include roof services within an eight-storey volume.

- Main changes to the DCP included the flexibility to locate and design a transit corridor along the northern side of the Plaza, use of Barker St to serve Plaza activities instead of allowing through-traffic.

Following the exhibition, the council received submissions from key stakeholders like Transport for NSW, and two adjacent landowners – Urban Growth NSW and The Green Square Consortium. Their submissions expressed support but raised minor issues regarding bus lanes and bus stops, parking facility, vehicular routes and management of potential noise and light pollution.16

These concerns were addressed and the proposal was sufficiently deliberated before the architects lodged a Development Application (DA), a formal request for consent (from approval bodies – State Government and Local Councils) to execute the proposed development.

Stakeholders (according to the IAP2 spectrum) participated to the degree of involvement. Participants included local businesses, neighbouring site developers, neighbouring residents, etc. The feedback objective here was to facilitate the development of the winning design proposal.

Conclusion

The winning entry was executed on site without many changes to its design – the result of a clear design strategy informed by the public. Together, the design team and the council had a clear design strategy and the commitment to deliberate with the community.

With global cities rapidly expanding to accommodate increasing population densities, many industrial lands are being subjected to urban renewal. Governments are developing new town centres through large green-field or brown-field projects and they are investing heavily on delivering world-class social infrastructure. Human centric approaches are being adopted at the urban scale to ensure the city’s vision aligns with the population needs.

For example, COS invited public feedback on a proposal to grant a licence for a market at the Green Square Plaza.17 In 2014, an intensive community survey was conducted to gain people’s views on the ongoing developments in Green Square. While such methods of engagement help the designers and give the community a sense of responsibility and ownership, technology can facilitate better participation and performance measures. In the case of this project, all competition entries and relevant information throughout the project was made available online and feedback was sought through discussion groups.

Although the council’s intention to include the community in the decision-making was good, better engagement methods could have attracted more participants. It is a tedious task to review so many entries or to read text-heavy files about amendments. Attendance to public consultations and focus group workshops is often low unless people feel deeply concerned or have an inclination to provide inputs.18 Strategies such as provision of childcare and incentives in the form of cash or prizes reduce such barriers to community participation. Survey reports are an old-fashioned way to measure performance.19

Through technology, we can find scientific and accurate ways to measure people’s preferences in built environments. Augmented reality, for example, could allow people to visualise the potential transformation of a space. Additionally, it would allow for real-time monitoring and measuring of behavioural changes of people while they virtually experience a proposed space.20

Evidence-based or insight-driven interventions take time, but also result in a more conscious design which eventually benefits the space users. Project deadlines and budgets can prevent designers from spending the time needed to understand community dynamics.21 The timeline of Green Square Library and Plaza indicates the challenge of community consultation in large-scale public projects. Everyday places should be designed innovatively but by using a human-centered approach. The training of design professionals does not include the basics of human perception which can help designer’s understand the impacts of their work. Frameworks and guidelines that analyse through a human-centred lens can help designers, clients, and stakeholders understand that they are accountable for the decisions made.22

References

1 Medium. 2017. What Is Human-Centered Design?. Available at: https://medium.com/dc-design/what-is-human-centered-design-6711c09e2779#:~:text=Also%20known%20as%20human%2Dcentered,those%20who%20experience%20a%20problem.

2 2013. Draft Planning Proposal Green Square Town Centre Library And Plaza. Sydney: City of Sydney, p.11.

3 Ibid.

4 Studiohollenstein.com. n.d. Available at: https://studiohollenstein.com/green-square-library-plaza/

5 Bonet Peitx, Ignasi (2017). “Innovative architecture for the contemporary library”. BiD: textos universitaris de biblioteconomia i documentació, núm. 38 (juny). http://bid.ub.edu/en/38/bonet.htm

6 Editors, A., 2018. AR Library Award Winners Revealed – Architectural Review. Architectural Review. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/awards/ar-library/ar-library-award-winners-revealed

7 Mackenzie, A., 2018. Square The Circle: Green Square Library In Sydney, Australia By Stewart Hollenstein In Association With Stewart Architecture – Architectural Review. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/square-the-circle-green-square-library-in-sydney-australia-by-stewart-hollenstein-in-association-with-stewart-architecture

8 Cheng, L., 2018. Newly Completed Green Square Library And Plaza Wins Global Library Award. ArchitectureAU. Available at: https://architectureau.com/articles/newly-completed-green-square-library-and-plaza-wins-global-library-award/

9 Rice, C., 2019. A Diorama In A Messy City: Green Square Library And Plaza. ArchitectureAU. Available at: https://architectureau.com/articles/green-square-library-and-plaza/#

10 Cheng, L., 2018. Newly Completed Green Square Library And Plaza Wins Global Library Award. ArchitectureAU. Available at: https://architectureau.com/articles/newly-completed-green-square-library-and-plaza-wins-global-library-award/

11 Ibid.

12 2013. Strategic Community Consultation Report – Green Square Library And Plaza. Sydney: City of Sydney, pp.2-8.

13 Ibid.

14 Cheng, L., 2018. Newly Completed Green Square Library And Plaza Wins Global Library Award. ArchitectureAU. Available at: https://architectureau.com/articles/newly-completed-green-square-library-and-plaza-wins-global-library-award/

15 2014. Post Exhibition – Draft Planning Proposal And Development Control Plan Amendment. Sydney: City of Sydney, pp.1-12.

16 Ibid.

17 Cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au. 2019. Licence For A Market In Green Square – City Of Sydney. Available at: https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/council/your-say/licence-for-a-market-in-green-square

18 Community Places. (2014). Community Planning Toolkit Community Engagement [Ebook] (p. 12). Retrieved from https://www.communityplanningtoolkit.org/sites/default/files/Engagement.pdf

19 Brackertz, N., Zwart, I., Meredyth, D., & Ralston, L. (2005). Community Consultation and the ‘Hard to Reach’ [Ebook] (p. 38). Institute of Social Research. Retrieved from http://library.bsl.org.au/jspui/bitstream/1/753/1/HardtoReach_main.pdf

20 Jamei, E., Mortimer, M., Seyedmahmoudian, M., Horan, B., & Stojcevski, A. (2017). Investigating the Role of Virtual Reality in Planning for Sustainable Smart Cities [Ebook] (pp. 13,14). MDPI.

21 Goldhagen, S., 2018. Journal 5 – Human Centered Design. Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health. Available at: https://www.urbandesignmentalhealth.com/journal-5—human-centered-design.html

22 Ibid.