The World we inhabit today is facing an uncertain future. One in which humanity will have to be able to adapt to vast fluctuations in climate, inevitably impacting everyday life in our urban environments. These fluctuations have come about due to our dependence on fossil fuels since the industrial revolution. However, the advancements in technology since that time have propelled human kind into a global dialogue of exchange, enabling us to become a universally diversified organism which has the potential to anticipate and withstand the changes in our societies, economies, and ecosystems that climatic uncertainty will bring in the not so distant future.

Globalisation, as a construct of living, has enabled the freedom and ease of movement to many places on the planet, enabling dense urban inhabitation in places where it would never have before been possible. Globally urbanised settlements have contributed to the dramatic changes in our climate which we are beginning to witness today. These climate fluctuations are only forecast to become more present and extreme, inevitably affecting the everyday lives of urban inhabitation. The need to construct our built environments to become adaptive and resilient to these extremes is now a necessity.

By 2050 the global population is expected to grow to 9.8 billion inhabitants, with 66% of those people projected to live in urban areas.1 This growth in urbanised living has coincided with the growth in global energy usage, which has increased by over 70% in the last twenty years.2

In 2012 the link between urban expansion and consumption was illustrated through the Black Marble photography series by NASA which provided clear images of the Earth at night.3 Through this, urban expansion is illustrated in the light coming from our built environment which breaches the Earths atmosphere and projects outwards into space, giving a portrayal of our urban settlements and the energy which they use and emit.

This growth, has come at the cost of constantly rising carbon dioxide emissions, due to our reliance on fossil fuels which is intrinsic in the production and transportation of those resources.

Twenty Sixteen noted the first year in recorded human history where the carbon dioxide levels in the earths atmosphere passed 400ppm (parts per million). The breaching of this threshold meant that it is unlikely that the concentration of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere will ever fall below this mark within the lifetime of people currently alive on the planet.4

The change in climate which we have witnessed over the last century has therefore become irreversible and we must begin to prepare ourselves in our built environments for the unknown changes that lie ahead. It is not now only necessary to construct our urban spaces to be sustainable, but also necessary to make them resilient for their human inhabitants to the changes in climate which are predicted to occur in the foreseeable future.

To integrate human resilience in the built environment, sustainability within architecture and urbanism needs to expand its scope. It needs to be able to adapt to the changes in climate which we are about to face in the near future in order to fulfill the needs of the people which it serves.

As a profession, architects think across multiple scales, which vary from the Extra Large of the building within its societal, economic, and ecological context to the Extra Small of the building detail design. This multi-scalar approach needs to be transient when designing resilience into our buildings and cities, and should integrate the social needs of people, with economic and ecological demands of the environment in which those people dwell. To be able to do this in an increasingly globalised society, we as designers need to relate global goals into our designs to ensure the resilience of the global citizen in our urban environments.

The outline for these global goals has been being constructed over the last decade, accumulating in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals(SDGs) in 2015.5 However, the call for a scientific understanding of the extent to which our current way of living is impacting our planetary ecosystem, and what the results of these effects will have on our societies and economies had been debated previous to the solidification of the United Nations report.

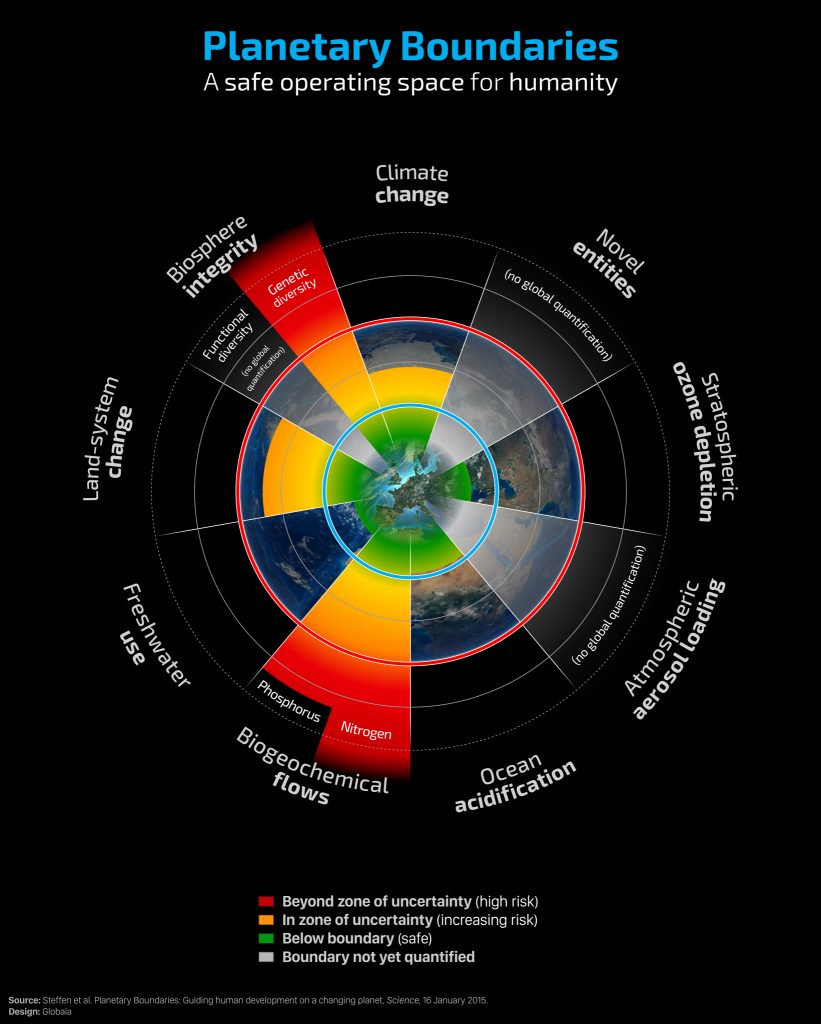

In a bid to measure the boundaries of our planetary ecosystem, Johan Röckstrom outlined the extent of our planet’s resilience in terms of planetary boundaries in 2009.6 Röckstrom shows that many of these planetary boundaries have already been breached, propelling the need for human kind to become more resilient in order to maintain current standards of living.

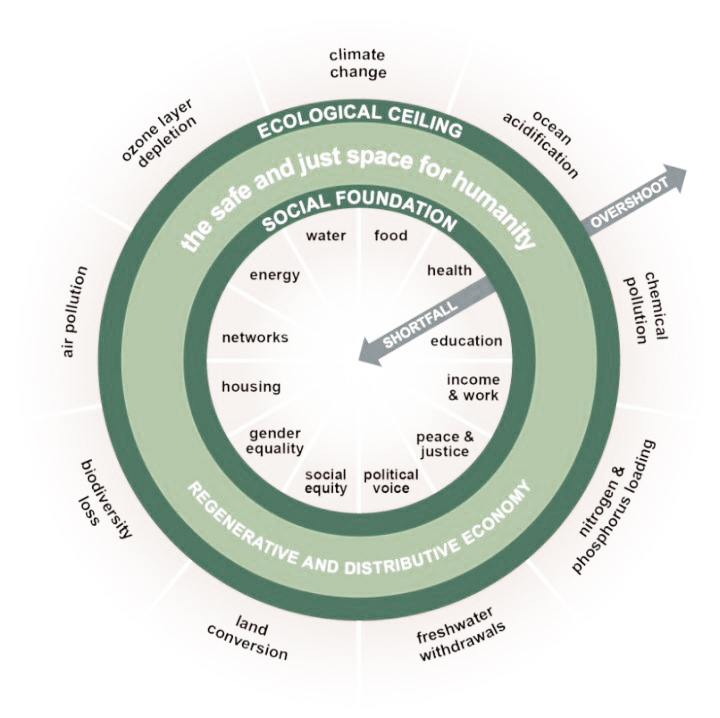

The economist Kate Raworth, in 2012, integrated these planetary boundaries into a circular economic model which brought the ecological resilience expressed by Röckstrom within a social and economic context. In her doughnut economic model Raworth designs a safe space for humanity which sits between the achievement of a social foundation and the containment within the planetary boundaries.7The integration of economical, social, and ecological sustainability within this model creates a mandate for a way of living which places people at the centre, creating a new model which adapts to fluctuations of people, rather than capital.

To equip our ever globalising societies with the instruments to become sustainable the United Nations set out their Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. The SDGs bring together social, economic, and ecological ambitions, creating prominent guidelines for nations to develop within a global partnership in a sustainable manner up until 2030.

However, the compartmentalising of the SDGs into a tick box of numbers, 1 through to 17, dissects the original integration of social, economical, and ecological sustainability which was outlined by the Club of Rome in 1972.8 In doing this, whilst responding to the three fold ambitions of sustainable development, the SDGs open up the possibility to achieve ambitions in isolation, creating the danger of fulfilling one goals at the expense of others.

In understanding this global shift towards sustainable development the need for its integration, and a push towards providing human resilience, in the built environment is becoming ever more necessary.

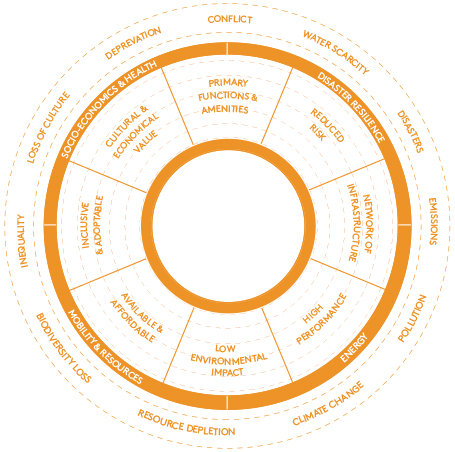

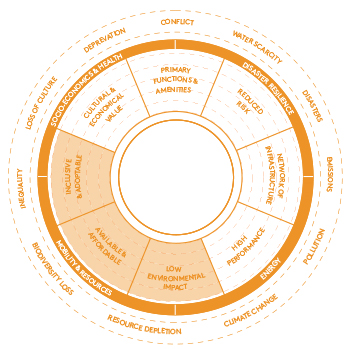

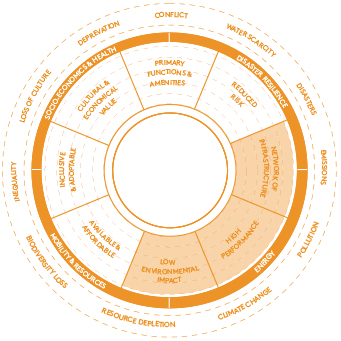

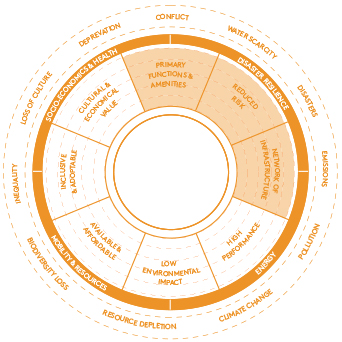

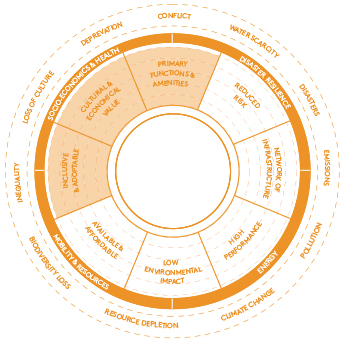

To address this, Atelier for Resilient Environmental Architecture (AREA) created an analysis and design framework which enables adaptive design solutions to the challenges which future urbanisation holds, allowing designers to respond with proposals that take note of the global issues which humanity is set to face whilst being routed in the localised needs of the people who use that built space.9 The AREA framework for human resilience argues that achieving social, economical, and ecological resilience are intertwined and each are of level importance.

To understand the resilience of the built environment at any given point, information is brought into the framework through four key topics;

- Socio-Economics & Health

- Mobility & Resources

- Energy

- Disaster Resilience

This synopsis correlates key information which can be taken from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive understanding of the localised context in which design projects are being implemented. Through doing this, the framework enables designers to understand the extent of which the context they are working in is resilient across multiple scales, from contributing to the global and to the local, and design appropriate solutions to the issues at hand. Designers are then able to gain an understanding of which parts of the four key topics their environment meets and where there are opportunities to improve that environment within a design project.

From this analysis, the extent of which a particular design project is capable of meeting each topic can be understood, and then implemented, through the fulfilment of eight goals which are;

- Primary Functions & Amenities

- Cultural & Economic Value

- Inclusive & Adoptable

- Available & Affordable

- Low Environmental Impact

- High Performance

- Network of Infrastructure

- Reduced Risk

In achieving these eight goals the built environment can be deemed to be resilient in a global context for the localised needs of the people who inhabit it at that time. In doing this, the move to a more human-centred design approach is set out in a measurable framework which enables designers, urbanists, and architects to concisely evaluate the challenges which they face, and design solutions which respond to the complex relations of resilience in our urban environments, activating building awareness to the social, economical, and environmental situations at hand.

Within this globalised society, the design of our built environment can become more responsive to global demands whilst meeting the local needs of people through the use of AREA’s framework in design. This comes through linking urban space and buildings to essential public and private Primary Functions & Amenities, in a digital and physical Network of Infrastructure, which supports people within those functions. The creation of buildings which are Inclusive & Adoptable, and Available & Affordable, for their users, through understanding their social, economical, and ecological needs within space. Whilst, in doing this, having a Low Environmental Impact which has High Performance in terms of both accommodating for the needs of people and the energy usage which it takes to do so. The retention and implementation of Cultural & Economic Value in the built environment, enabling people to feel linked to the society of space, and to be able to feel both culturally and economically secure within it. All of which leads to Reduced Risk and ultimately human resilience, creating a society which is secure, whilst constantly adapting to the ever changing needs of the global citizens who now inhabit it.

The need to design in resilience to our urban spaces, enabling them and the people within them to adapt to the changing future which lies ahead is a major challenge for those within the built environment today. Our cities need to become more responsive to the needs of their environment and the people who inhabit them, to fully prepare humanity for the ever changing unknown, which lies ahead.

Framework for Human Resilience

Key Topics for the Built Environment, Atelier for Resilient Environmental Architecture, 2018

References

1 United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs, 2017 Revision of The World Population Prospects, https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/, accessed 26/02/2018

2 International Energy Agency, Key World Energy Statistics, http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/KeyWorld2017.pdf, p34

3 NASA, The Black Marble, https://www.nasa.gov/topics/earth/earthmonth/earthmonth_2013_5.html

4 The Guardian, The world passes 400ppm carbon dioxide threshold. Permanently, last edited 28th September 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/sep/28/the-world-passes-400ppm-carbon-dioxide-threshold-permanently

5 United Nations, “Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” United Nations (2015), < https:// sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf>

6 Johan Rockstrom et al., Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity, Ecology & Society: 14 (2009, The Resilience Alliance), https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/

7 Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, (2017, Random House Buisiness Books, London)

8 Club of Rome, About Us – History, (2018) < https://www.clubofrome.org/about-us/history/>

9 Atelier for Resilient Environmental Architecture, Towards a Habitable Earth, (2018, Delft University of Technology, Delft)