In recent times, the idea of the ‘smart city’ has taken wings. Essentially, urban and city planners now work towards streetscapes that are equipped with modern information and communication technologies, such as vehicular automation and IoT-enabled systems, with the aim to improve the operational quality of streets and cities. Smart tech and data analyses help planners understand and estimate the use of streetscapes to optimise city functions and, in turn, drive up growth and improve quality of life for city dwellers.

In addition to the operational data that is purposefully being collected, there is an increased data stream that relates to human experiences that is offered up unintentionally (through plotting daily activities online on multiple social platforms). When we look to utilise the former to “smarten” our built environments, we might also consider working with the experiential data to accommodate such feedback into designing neighbourhoods and streetscapes that are sensitive to the people that reside in them. Working towards “conscious” cities should stem from the want to create environments that use the urban tech growth to address the diverse psychological and social needs of the inhabiting population.

The Seaport neighbourhood, just poking south-east of Boston’s city centre, is a sprawling canvas of the recently (re)developed land, which until the late 2000s used to be a muddy and abandoned part of the city’s Harbour. Once a thriving shipping area and home to warehouses and sea-trade, the neighbourhood now houses office buildings, condominiums, high-end retail stores, and restaurants. These amenities, with their proximity to downtown Boston, have made the Seaport a prime spot for real estate growth in the last decade.

There is even reference to the Seaport being the Innovation District, for its recent influx of tech companies, start-ups, design firms, Lyft-sponsored NuTonomy cars that drive themselves around the block, parking lots boasting electric car charging stations and potentially a smart electric grid — a neighbourhood very much on its way to becoming “smart”.

The analysis that follows is based on two years of working in the Seaport and graduate coursework taken in Interior Architecture at Suffolk University in Boston, MA. The neighbourhood was traversed collectively, as a class, with end-user experts and volunteers from the Institute of Human Centred Design (IHCD), Boston.

Let’s walk down the manicured Seaport Boulevard: imagine walking through wide streets lined with retail fronts on both sides, glass enveloped building lobbies that promise luxury amenities, catching glimpses of the Atlantic, in between patches of green (sometimes real, sometimes fake grass) that host outdoor yoga in the summer. There’s the constant movement of people who look like they’re on a mission; to or from the office, heading on errands before the midday peak. You look around to find a place to rest — benches aplenty, but nothing to give them any reprieve from the sun. As you spot your friend across the block and hurry over, you narrowly avoid falling on your face, because the crossing curb cuts aren’t where you’d thought they’d be. You jay-walk across the street because the walk-sign has been on hold for a while. And when you finally reach your destination, the overcrowded cafe, you can’t fathom the lunchtime queue and decide to settle for a take-away and return to the office instead, where the glare from the glassy building facades won’t hit you straight in the eye.

This series of unfortunate events may not happen all at once to any individual, but this narrative was strung together from the user experts on the project walk, and based on personal experience. In an effort to capitalise on the real estate developments in the area, it would seem, a multitude of basic, smaller scale human-centric comforts were left unattended.

Looking Closer :

Lost with Google Maps

The over-exuberant branding of newly erected buildings drown out any (if existing at all) street graphics that would help the pedestrian orient themselves. With bouts of construction all over the place, even the MBTA station signs, that are generally landmarked by the T logo, can be difficult to get to because diversions are not clearly marked. If arriving via a ride share app, you might find your venue without much concern. However, should your mobile device succumb to a low battery, in the Seaport you would not be able to rely on the informative map displays (describing distances to landmarks, public facilities and transportation etc.) that line downtown Boston. If working towards a pedestrian-friendly neighbourhood, there should and must be careful attention towards environmental graphic design — such as analog signs that don’t rely on being connected to the internet, and are easily understood — that enhances any encounter with the street.

Curb Cuts, But Where?

The curb cut (that short ramp cutting through a curb at traffic intersections), a simple footpath design element, helps everyone traverse the city, not just the differently abled. But however well meaning the intention behind the cut, what is seen happening in the Seaport is that individual properties often take liberties with its design. Sometimes they are placed at corners of intersections, while sometimes they are inset on the path itself — the reason behind such decisions remaining elusive to the pedestrian.

Hardscape and Street Furniture

When the motivation behind developing a neighbourhood is profiting on the square foot of amenity space, green spaces and soft landscape often become amenities as well. Although there is some logic behind the ratio of open space to built space, the calculated nature of the Seaport Common and its smaller green spaces feel coerced into planning, as if they were put there reluctantly, or as a last minute thought to programming. Sprinkled across certain properties, there are retail and restaurant fronts that spill into the open hardscapes, creating cozy outdoor environments. These, however, are only sometimes non-patron friendly and do not form a permanent part of the public amenity. The landscape surrounding the built environment requires design elements — street furniture, say — that invite interaction and are easily adaptable to varying needs of the people passing through the neighbourhood.

Owning the street

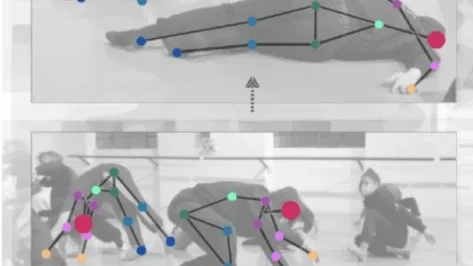

When designers and planners focus on the smart city, there is also considerable emphasis on redesigning what the function of the street should be. The interaction between smart transportation and human movement needs to be analyzed better to provide meaningful solutions that benefit all user groups. Visual and sound cues at traffic intersections (traffic signals) need to account for variations in human ability as well as ensure optimal waiting times for vehicular movement.

Making a Community

What has happened is that the Seaport district has been born out of (mostly) real estate ventures. Alongside the presence of the Institute of Contemporary Art, District Hall, the Convention Center, and other cultural venues, the Seaport is a destination rather than the neighbourhood it is vying to be. This is currently being addressed by local authorities by encouraging stakeholder participation in community development projects. On a larger scale, there might be scope to rethink the parcel divisions. On a smaller scale, however, there needs to be opportunities within the streetscape for people to linger without feeling like trespassers — the solution to this may come out of the wider outreach programs that include people with varying attachments to the neighbourhood. An example might be breaking up the long streets that serve as vehicular thoroughfares into portions to promote pedestrian presence. This could be done by using innovative streetscape elements, or basic ones like natural green spaces, that can evolve with use, in addition to the outdoor pockets created by businesses.

With Boston’s Seaport under the microscope, well-intentioned design elements are present, such as larger street crossings, wider pathways for foot traffic, and valet drop-off and/or pick-up points for ride sharing incorporated in building landscapes. But despite these motives, the human element has been overlooked, and the full spectrum of human abilities has not been addressed. More in-depth research and collaboration with experts on human centred design and smart city initiatives may result in feasible solutions that bring about a better street experience. Conscious urban design would transform people’s interactions with the streetscape, making them dynamic, adaptable (in view of needs and challenges), and contextually significant.

Over the last few decades, architects and designers have been designing for accessibility in the built environment, with a focus on motor disability. In recent years, the attention has peaked towards universal and human centred design. The inclusivity of architectural design has also been questioned — there are multiple tools that designers and planners use to restrict or increase public access to an urban space. Good design, especially with regards to a universal and public element like the street, should cater to the convenience of all who use it, from orienting oneself based on visual cues and understanding right-of-ways, to mapping nearby facilities and perceiving a sense of urban community. Truly vibrant, efficient, and conscious streetscapes and neighbourhoods require user experience, not technology, to be placed at their centre.

References

Palti, I. and Bar, M. (2018). A manifesto for conscious cities: should streets be sensitive to our mental needs?. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/aug/28/manifesto-conscious-cities-streets-sensitive-mental-needs [Accessed 11 Oct. 2018].