For generations, learning thrived in open landscapes. But traditional classrooms in recent decades have followed a rigid, standardized design—four walls, rows of desks, and artificial lighting. While being the most prominent, this approach often isolates students from the natural world. As education shifts further into digital spaces, children spend more time on screens than in nature. This cultural shift emphasizes the need for learning environments that allow students to choose their physical environments over their gadgets. Simultaneously, our urban landscapes are increasingly dominated by concrete structures, which are encroaching and replacing lush green spaces every day. With people now spending around 90% of their time indoors, it is evident that our environment is way behind the curve, and there is a pressing need to play catch-up.

This is where biophilic design offers a transformative alternative. Biophilic Design, in the most traditional sense, means integrating nature into our built environment.2 The concept became popular when research found nature views to be healing to patients in hospitals, employees in offices, and children in schools.1,3-8

Outdoor learning is not a novel concept; it has been an integral part of education for centuries. From the ancient Greeks conducting philosophical discussions in open-air academies to the Scandinavian ‘forest schools’ that immerse children in nature-based learning curricula, educators have long recognized the benefits of engaging with the outdoors. Outdoor learning has been time-tested globally as a better form to cultivate intellect, where “the mind is without fear and the head is held high,” as Rabindranath Tagore has said.

Yet, as modern classrooms moved indoors, this connection to nature faded. Today, with growing awareness of its cognitive, emotional, and social advantages, outdoor learning is experiencing a resurgence, seamlessly integrating with the curriculum and fostering curiosity and well-being.

Although outdoor learning or nature-based learning does not necessarily translate to biophilic design, this article focuses on the latter, recognizing that not all schools have access to natural spaces within their grounds. Additionally, even if such landscapes are available, they do not always offer safety or security, especially for kids who want to immerse themselves in the environment.

Biophilic design bridges this gap, embedding nature into built environments consciously to support mental, physical, and emotional well-being.11 In this piece, we will discuss how biophilic design can transform schools and make outdoor, nature-based learning a reality. We’ll additionally discuss how powerful biophilic design is in making school environments more than just places to learn, but places that spark curiosity and exploration for all students from early childhood to high school, and beyond, by examining its intersections with architecture, child psychology, pedagogy, and environmental sustainability.

Bridging Theory & Practice in Biophilic Design

Outdoor Learning, or nature-based learning, isn’t just about taking education outdoors; it’s about integrating natural elements into the learning process, fostering hands-on, experiential learning that goes beyond the walls of a traditional classroom. Studies have shown that students who spend time with biophilic elements like plants, water features, natural materials, and even natural patterns are more likely to feel engaged, retain what they learn, and develop better social behaviors. Not only does it help them academically, but it can also foster growth in emotional resilience, curiosity, and engagement. Combining biophilic design and outdoor learning can create such positive spaces through outdoor classrooms, school gardens, and forest schools, allowing students to engage with nature through direct interaction.

The essence of biophilic design lies in integrating natural elements such as plants, water features, natural materials, and organic patterns into classrooms, whether indoors or outdoors. But the central ideology of this paper is on outdoor nature-based learning, to allow for an exploratory learning model in schools to reflect growing concerns about sick-building syndrome, screen dependency, mental health, and environmental disconnect among children.

For this essay, we conducted a rapid scoping review of 6 online blogs and about 12 scholarly articles to explore the impact and implementation of nature-based learning in schools. Numerous studies highlight the positive effects of nature exposure on children’s cognitive and psychological well-being. Research suggests that outdoor learning environments enhance attention spans, reduce stress levels, and promote pro-environmental behaviors and emotional regulation. For example, the An Darach Forest Therapy program in Scotland (“An Darach” meaning “The Oak” in Gaelic) found that exposure to green spaces helped reduce anxiety, depression, and attention deficit disorders in children aged 12-17.

Furthermore, hands-on exploration of nature stimulates curiosity through exploration and intrinsic motivation. A Michigan Medicine study (2023) found that childhood curiosity is strongly associated with academic achievement, particularly in STEM. Outdoor environments, characterized by their dynamic and ever-changing nature, promote problem-solving, creativity, and adaptability—skills that are less effectively cultivated in static indoor settings. The benefits of nature-based spaces extend to more, as suggested by evidence. A review of outdoor education programs found that students who learn outdoors performed better on tests, exhibited improved focus, and information retention compared to peers in traditional classrooms. Classrooms with plants show a 14% increase in performance in subjects such as mathematics, science, and spelling. Additionally, outdoor settings foster teamwork, resilience, and confidence, helping students, especially those who struggle in traditional settings, engage more fully with the curriculum, particularly among children struggling with conventional learning structures.

Breaking Boundaries: Exploration and Curiosity in Outdoor Learning

Outdoor learning spaces spark children’s curiosity, turning everyday moments into opportunities for discovery. Nature is a gateway to the ever-changing environment around the world, and encounters with nature may encourage children to ask questions, make connections, and develop critical thinking skills through hands-on engagement.

This is often crucial for education because the learning psyche of students is deeply intertwined with their environment. Outdoor play in school has a profound impact on cognitive creativity and resilience in addition to offering them a valuable break in between classes and providing a breath of fresh air. Sensory-rich environments enhance learning—whether it’s the sensation of wet grass underfoot, the sound of birds, or the sight of a butterfly. These experiences anchor knowledge in memory and deepen emotional connections to learning. Breaking away from traditional classroom structures is central to fostering this dynamic learning experience. Nature-based learning disrupts the traditional model by offering a flexible and immersive environment where learning happens through doing. A tree stump becomes a seat, a garden bed turns into a biology lesson, and a shaded grove transforms into a collaborative discussion space, making lessons more enjoyable and flexible. By integrating natural landscapes into education, students not only improve academically but also develop a deeper connection to their environment, fostering environmental stewardship and a better understanding of life’s interconnectedness. The next section discusses some cases where schools have embraced the power of nature in their learning modules. We shall also dive into exploring nature-centric design and the pros and cons of biophilic school spaces, considering cultural perspectives along the way.

Case Study – I: An American Dream

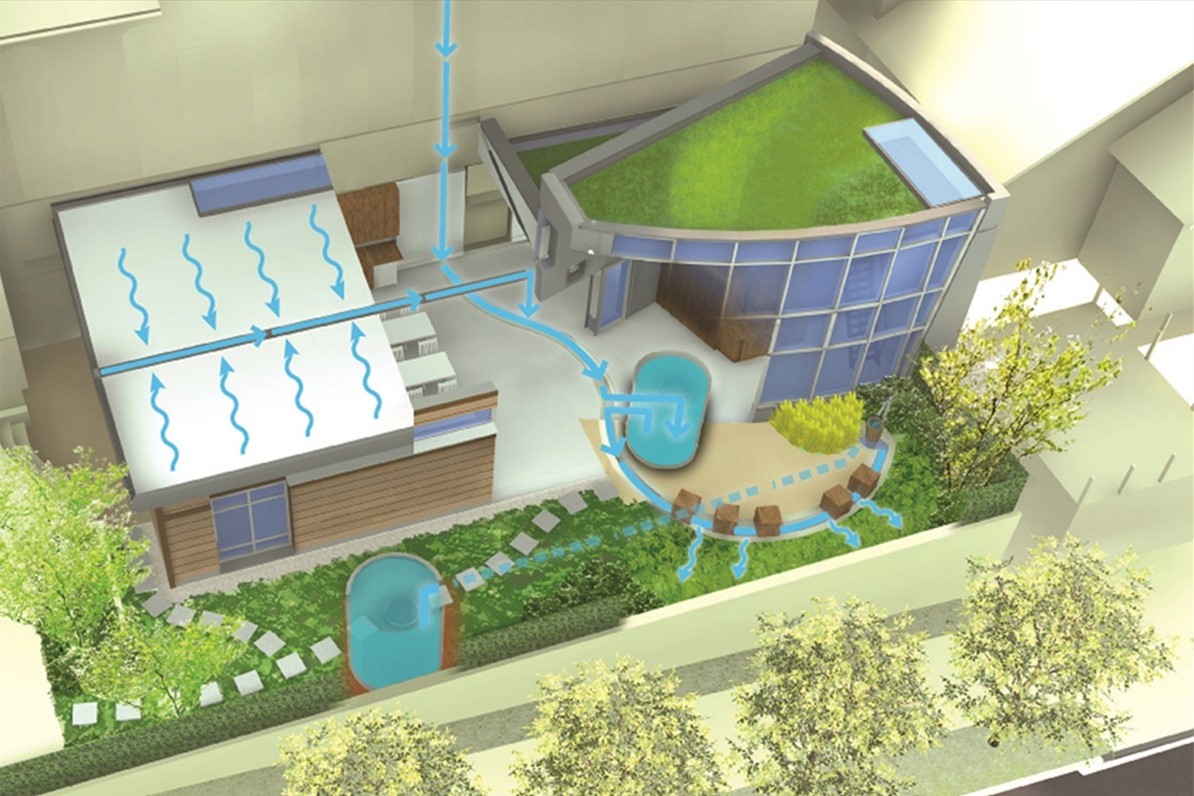

While nature-based design is slowly becoming more common in U.S. schools, very few have fully embraced it as part of their core teaching philosophy. One standout example is the Bertschi School Science Wing in Seattle. As the first Living Building Challenge-certified school project under the Living Future Institute, its architecture embodies sustainability and student engagement. The institute was designed by a dedicated team at KMD Architects, whose objectives were to embody biophilia into the philosophy of teaching. Through their design, the school prioritizes student engagement and hands-on learning. Some images of the school are provided below (Figures 1-4).

Innovative Learning Outcomes

The Bertschi School Science Wing transforms traditional learning spaces by seamlessly integrating nature into the fabric of the building. Through features like the living green wall, stormwater runnel, and ethnobotanical garden, students get to interact with and explore ecological systems and sustainability in a way that feels real and hands-on. These features make learning more sensory-rich, engaging students’ senses—sight, touch, hearing, and even smell—in a way that traditional classrooms can’t.

Often, biophilic design is mistaken as an aesthetic addition to a traditional building, but the Bertschi School uses it strategically. The green wall, for example, purifies the air and filters greywater from classroom sinks improving the Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ), in addition to being an aesthetic feature. Students engage directly in the water cycle and learn how plants thrive on the greywater. The Stormwater Runnel channels rainwater into a cistern, making the hydrological cycle tangible and transforming abstract scientific concepts into observable phenomena. The design encourages exploration and discovery through natural systems. The textures, shapes, and colors of space spark students’ curiosity and get them to learn through sensory experiences. Every day, they engage with space, diving into scientific inquiry and even taking on roles as environmental stewards.

Unlike traditional classrooms, Bertschi’s design allows students to observe nature’s cycles firsthand. Whether they’re watching roof moss bloom, harvesting plants from the garden, or seeing how weather affects energy use, this connection sparks wonder and gives them a deeper understanding of the world around them, teaching them concepts like change & metamorphosis.

Case Study – II: An Indian Revolution

While there are plenty of biophilic schools around the world, this article chose to shine a light on an Indian example for a few reasons. First, it connects personally, as I studied architecture in India before pursuing my graduate degrees in the U.S. Second, biophilic school spaces and designs vary across cultures, influencing usage, materiality, and educational philosophies. India offers a distinct perspective through vernacular materials, biomimicry patterns, and cultural narratives embedded into its learning environments.

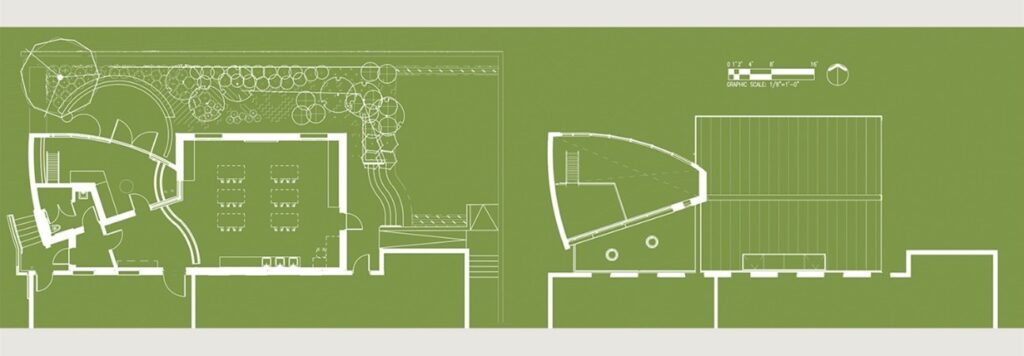

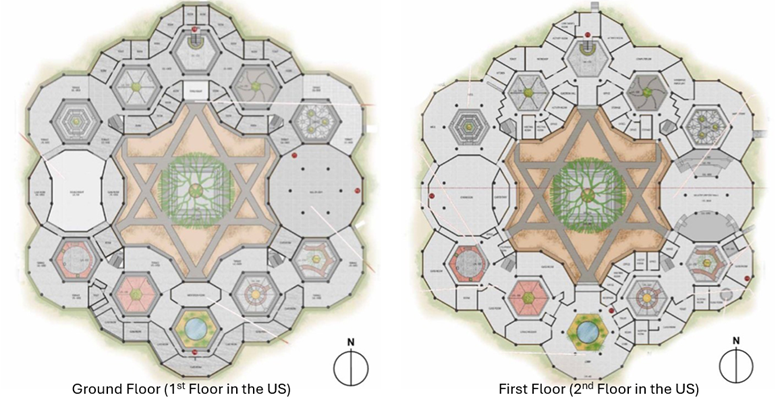

Among the many biophilic schools in India, the Mirambika School in New Delhi stands out for its blend of biophilia and human-centered design to enhance the learning experience. Situated in the capital city, this experimental school, designed by Sanjay Prakash of Studio for Habitat Futures, serves as a global example of how architecture and nature enhance education. This selection also holds personal significance, as my undergraduate research involved “Auroville” in southern India, inspired by Sri Aurobindo’s educational philosophy. His philosophy on education revolved around open, flexible spaces connected to nature, fostering exploration and discovery. He believed learning should be organic, fluid, and attuned to nature’s rhythms, nurturing the mind, body, and spirit while stimulating curiosity and creativity. The connection between Mirambika and Auroville’s ideals adds depth to our exploration of biophilic learning environments. Located on a site along Aurobindo Marg, its layout (Figure 5) is rooted in fostering creativity, exploration, and holistic learning. The design intentionally blurs boundaries between built spaces and nature, creating a seamless flow between indoor and outdoor environments.

One of the most striking features of Mirambika School is its use of courtyards. Twelve smaller courtyards surround a central courtyard, symbolizing ‘Aditi,’ the fire of creation in Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy. These spaces provide natural light and ventilation, minimizing the need for artificial systems. Nature remains integrated into learning spaces, creating a continuous connection and a constant presence in students’ daily activities. The open-plan design (Figures 5-7), with low partitions instead of walls, promotes collaboration and flexibility, while the Hall of Light with triangular skylights offers serene illumination for reflection.

Anyone who has visited Delhi knows the harsh climate of the City. Acknowledging Delhi’s climatic challenges, the building adapts to the heat through strategic orientation and materials to enhance thermal comfort. The west-facing facade is solid to block heat, while dense tree canopies and inward-facing courtyards enable passive cooling and cross-ventilation, maintaining a comfortable indoor climate.

Learning Through Space

Mirambika School exemplifies how built environments can influence pedagogy by moving from conventional classrooms. The integration of organic elements and flexible spaces encourages experiential learning, fostering independence, curiosity, and environmental awareness in students. Each design choice supports a learning atmosphere that nurtures exploration and self-direction.

Two Schools, Two Worlds: A Comparative Dive into Biophilic Learning Spaces

At first glance, the Bertschi School in Seattle and the Mirambika School in New Delhi share a common goal—integrating nature into education. However, their approaches differ significantly, shaped by cultural, climatic, and philosophical influences.

Bertschi takes a high-tech, structured approach with a living wall that filters greywater and a hydrology-focused runnel. It’s a hands-on, scientifically driven model. In contrast, Mirambika embraces a more organic, free-flowing design, inspired by Aurobindo’s philosophy. Courtyards and open-plan classrooms dissolve boundaries between built spaces and nature, making nature an active part of learning.

Both schools excel in using natural light and ventilation, but Bertschi focuses on ecological processes, while Mirambika creates an evolving, immersive experience. Bertschi is rooted in sustainability, while Mirambika emphasizes experiential learning.

Bertschi is a beacon of sustainability, with solar panels, water recycling, and controlled environments. However, this structured approach might limit the kind of spontaneous, free-form exploration that often happens outdoors. Mirambika, with its open, flexible spaces, fosters independence and adaptability. But Delhi’s harsh climate may present challenges when it comes to environmental control. Bertschi leans on technology for sustainability and creating a controlled, eco-friendly space. Mirambika, on the other hand, represents a more philosophical, immersive approach, where nature itself becomes the classroom.

Conclusion

The article sheds light on two sides of a design ideology: one from the West with Bertschi School and the other from the East with Mirambika School. Both schools demonstrate how integrating nature into educational spaces transforms learning. At their core, both schools embrace the truth that children’s natural curiosity thrives in environments that encourage interaction, exploration, and immersion. They thrive in environments that let them do more than just observe—they need to interact, question, and immerse themselves in their surroundings.

Biophilic design, especially in areas with limited organic green spaces, offers a way to bring nature into the classroom in a meaningful way. These spaces become more than just classrooms; they become dynamic learning labs that spark curiosity, promote creativity, and inspire a deeper connection to the world around them. However, biophilic strategies must be adapted to different geographies. In regions with harsh winters, minimal sunlight, or arid climates, integrating nature may require enclosed green spaces, adaptive materials, or artificial lighting that mimics natural cycles to ensure accessibility and effectiveness worldwide. This was the primary reason for discussing two cases: to understand contextual applications and cultural pros and cons of nature itself as a design element.

As designers, architects, and researchers, we have the power to redefine learning environments and break free from conventions. We have the knowledge and expertise to create immersive, nature-infused spaces that have the potential to positively impact the lives of students and educators alike. The ongoing research into the benefits of biophilic design and the built environment highlights the magic that these elements bring. However, the evidence we gather must be not only understood but actively applied in real-world settings. And through that, we become advocates for healthy design to tomorrow’s architects and researchers.

References

- Evans GW, McCoy JM. When buildings don’t work: The role of architecture in human health. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1998;18(1):85-94.

- Ryan C, Browning W, Clancy J, Andrews S, Kallianpurkar N. Biophilic design patterns: Emerging nature-based parameters for health and well-being in the built environment. Archnet IJAR. 07/12 2014;8:62-76. doi:10.26687/archnet-ijar.v8i2.436

- Christopoulou-Aletra H, Togia A, Varlami C. The “smart” Asclepieion: A total healing environment. Archives of Hellenic Medicine. 2010;27(2):259-263.

- Mostafavi B. Exploring the Link Between Childhood Curiosity and School Achievement. University of Michigan: Health Lab. https://www.michiganmedicine.org/health-lab/exploring-link between-childhood-curiosity-and-school-achievement

- Closs L, Mahat M, Imms W. Learning environments’ influence on students’ learning experience in an Australian Faculty of Business and Economics. Learn Environ Res. 2022;25(1):271-285. doi:10.1007/s10984-021-09361-2

- Duke J. Integrating Better Living Into Architecture. University of Cincinnati; 2024. 7. Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 1984;224(4647):420-421.

- Ulrich R. Health Benefits of Gardens in Hospitals. 01/01 2002;

- Dean SN. Seeing the forest and the trees: A historical and conceptual look at Danish forest schools. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education. 2019; 10. Berebon C. Tagore’s Philosophy of Man and Nature: A Study in Environmental Ethics. International Journal of Environmental Pollution and Environmental Modelling. 6(2):104-113. 11. Frumkin H. Beyond toxicity: human health and the natural environment. Am J Prev Med. Apr 2001;20(3):234-40. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00317-2

- Loose T, Fuoco J, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, et al. A Nature-Based Intervention and Mental Health of Schoolchildren: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. Nov 4 2024;7(11):e2444824. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.44824

- Davis B, Rea T, Waite S. The special nature of the outdoors: Its contribution to the education of children aged 3–11. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education. 2006;10:3-12. 14. Chawla L. Benefits of nature contact for children. Journal of Planning Literature. 2015;30(4):433-452.

- Turtle C, Convery I, Convery K. Forest schools and environmental attitudes: A case study of children aged 8–11 years. Cogent Education. 2015;2(1):1100103.

- Ibáñez-Rueda N, Guillén-Royo M, Guardiola J. Pro-environmental behavior, connectedness to nature, and wellbeing dimensions among Granada students. Sustainability. 2020;12(21):9171. 17. Clark C. EXPLORING THE AFFORDANCES OF OUTDOOR LEARNING: HOW TEACHERS UTILIZED THEM TO ENHANCE THE LEARNING EXPERIENCE. University of Saskatchewan; 2023. 18. Engelen L, Bundy A, Naughton G, et al. Data from: Increasing physical activity in young primary school children – it’s child’s play: A cluster randomised controlled trial. 2013. 19. Wineland T. Meet the outdoor school where recess lasts all day and children thrive. Standtogether.

- Watchman, M. Biophilic primary schools in cold climates: Design opportunities fostering multisensory experiences and well-being. 2021;

- Sibia A. Education for life: The Mirambika experience. Foundations of Indian Psychology, Volume 2: Practical Applications. 2011:156.

- Gupta B. Sri Aurobindo. Thinkers of the Indian Renaissance. 1982:191-206. 23. Kaur H. IMPLICATIONS OF EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY OF SRI AUROBINDO IN THE 21st CENTURY.