If naturalist Charles Darwin, personality psychologist Gordon Allport, and dystopian futurist Aldous Huxley were reborn today against the backdrop of our current digital age, what would they think of smart phones, wearable devices, and mobile virtual reality (VR) headsets? Over the next five to ten years, devices will be created—prototypes already exist—that allow us to integrate the physical world with layers of mixed reality (MR) in a pair of glasses or a single head mounted display (HMD) unit.

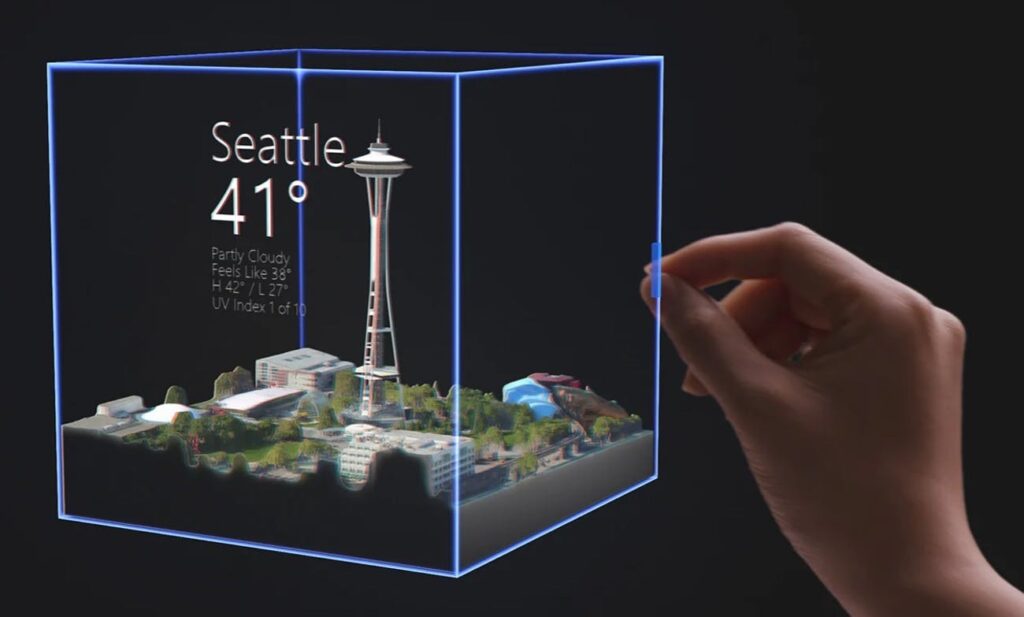

The arrival of MR—a combination of augmented and virtual reality—seems inevitable ever since the launch of Google Glass in 2013. Since then, developers have been racing to deliver wearable devices with powers originally classified only as science fiction. These capabilities include augmenting reality with your own physical world, projecting high resolution 3D images, and manipulating those images with your hands. By 2025, the total market size of the MR industry is estimated to be worth between 80 and 162 billion1.

The Fourth Transformation

As the next decade unfolds, we are on the cusp of what some futurists refer to as the “fourth transformation”1. The first paradigm shift in the 1970s was the move from typewriters to computers; the Macintosh ushered in the second transformation in 1984 (icons replaced text commands); and the third brought our fingers directly on to the screen (iPhones and touchscreens). We are now witnessing the fourth transformation, or the rise of technology that will enable us to touch the air in front of us and manipulate detailed 3D holograms while sharing the experience, and interacting, with others.

Dozens of companies—from major players like Apple, Microsoft, and Google to smaller start-ups like Magic Leap—have already invested heavily in MR research and development. Proponents of MR headsets emphasize the benefits of freeing up hands and raising eyes to engage with other users.

One need not be a programmer, coder, computer specialist, or tech guru to appreciate the rapid changes we are experiencing right now and recognize the transformations looming on the horizon. These changes mostly involve Mixed Reality (MR; a blend of VR and AR), machine learning (formerly “artificial intelligence”), and point cloud mapping. Psychological science will likely have a part in understanding how to best use this technology. The crucial question we need to answer is this: Do these new technologies promise to improve well-being—or will they make existing quality-of-life challenges even more difficult to manage? The following sections will explore this question from three perspectives: mental and physical disorders, isolation, and biophilic design.

Mental and Physical Disorders

A growing body of research supports the connection between urbanicity and various aspects of mental health, including disorders with psychotic elements (e.g., schizophrenia) and non-psychotic elements (e.g., loneliness and depression). The association between urbanicity and risk of schizophrenia has been documented in multiple studies2,3. Greater levels of urbanicity, measured by overall population or density, are correlated with a risk of schizophrenia that is up to 2.37 times higher than in the most rural environment2.

Recent research has explored potential mechanisms linking social exclusion in urban environments to psychosis. Evidence suggests that factors such as social fragmentation and deprivation may play direct or indirect roles3. A meta-analysis of psychiatric disorders in rural versus urban environments within developed countries found higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders in urbanized areas4.

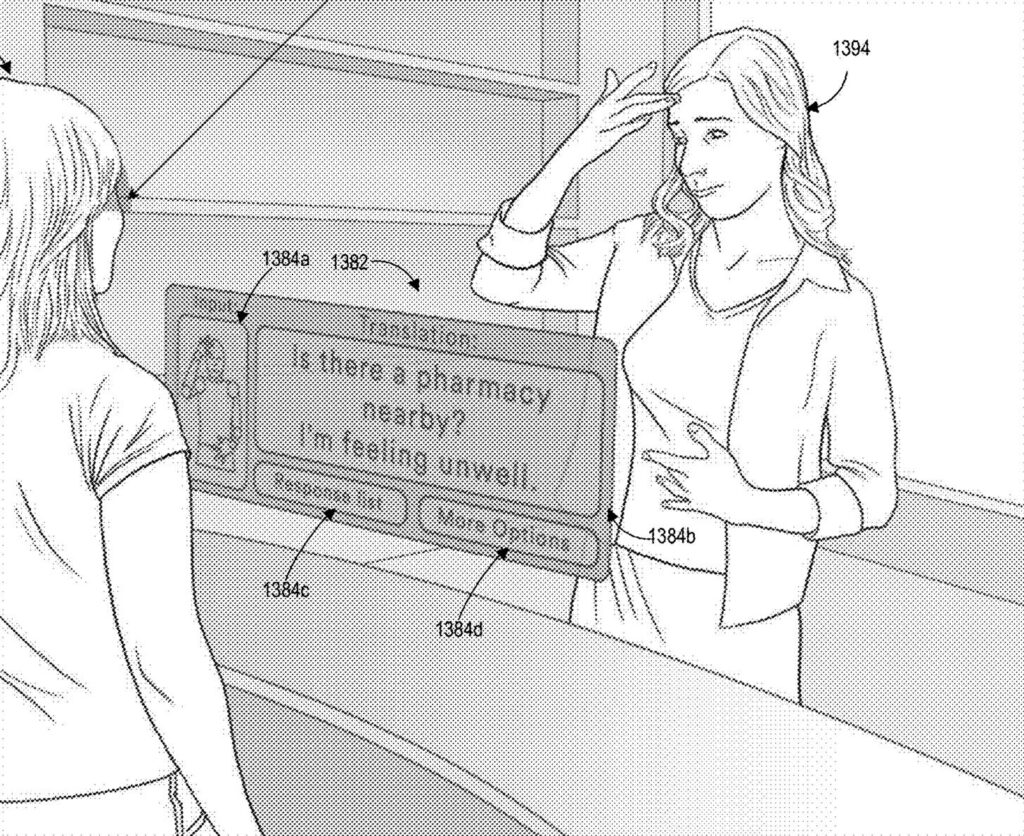

Hands-free MR technology has the potential to help with mental illnesses including autism, phobias, and schizophrenia. The company MindMaze, for example, introduced NeuroGoggles which use brainwaves to help schizophrenics manage volatile mood swings. MR is also giving the freedom of mobility to the hearing impaired. HoloHear, a Microsoft HoloLens application, converts speech into language and gives deaf people ability see a 3D avatar signing the words. This could easily be translated into languages across the globe. Basically, it works as a personal translator. Other companies are working on similar solutions.

MR systems are now being used to encourage autistic children toward more imaginative play. Autism Speaks has funded a project to teach autistic teens about social skills in job interview settings and meetings with new people. Psychological problems, such as spider and cock-roach phobias, can now be treated using MR exposure therapy. In this treatment, the patient can actually see his or her own hands at the same time the holographic spiders are crawling up their arms. Other applications include an MR treatment for phantom limb pain, overlays for surgeries, and post-stroke hand rehabilitation.

Social Isolation

Spatial computing is mobile and relies on hand gestures. Instead of being tethered to a computer and using a mouse or holding a smartphone, MR systems allow us to move around wherever we want. The barriers of the screen promise to disappear as will the era of missing out on vital social cues because eyes are fixated on digital devices in hands.

Social isolation in cities is a growing epidemic. The percentage of American adults who say they are lonely has doubled since the 1980s from 20 percent to 40 percent5. According to a 2013 survey conducted by ComRes on behalf of Radio 2 and BBC Local Radio, 52% of Londoners feel lonely. A large cross-cultural comparison of rural and urban areas in developed countries found that urban living raises the risk of mood disorders by 39%4.

The human desire to seek out all varieties of interactions, ranging from momentary eye contact to long term intimacy with partners, represents a basic need as fundamental to human nature today as it was to our Pleistocene ancestors. A number of studies point to the psychological effects of missing out on meaningful social interactions. At any given moment, 20% of all people are unhappy because of social isolation6. An individual’s chances of sickness or death are doubled for those who are cut off from friendships and family7.

Similar to smoking and obesity in scope, loneliness—which often triggers stress—has been linked to many diseases and, among mice, can even increase the growth of cancerous tumors8. Isolation is so powerful that recalling memories of being snubbed or social excluded often leads participants to report colder room temperatures than those who were asked to recall happy times with friends9.

More research is needed to articulate precisely how spatial computing will impact social isolation, but early indications point to some positive news. In most cases MR headsets bring users together rather than pulling users into solitary bubbles. In contrast to handheld mobile devices that force people to bury their heads and avoid human contact, MR headsets demand that you look up to interact with the world around you. Instead of being immersed in a digital world cut off from others, MR actually encourages social interactions. The recent world-wide success of Pokemon Go (a gaming app using MR that requires mobility to play) speaks to this.

Biophillic Design

We already know a good deal about how physical spaces affect mood and activity. For example, while everyday places like coffee shops and dorm rooms influence emotions, it is also true that we choose places based on our mood, or the mood we would like to achieve10,11. What will city life be like when we can digitally manufacture physical elements in our lenses to achieve specific mood states? Existing MR system are already capable of producing holograms so realistic it is difficult to discern where physical reality ends and the virtual environment begins. By harnessing this power, we can insert biophillic design features with surgical precision to maximize health and well-being.

Modern technology, structural designs, and construction materials allow us to comfortably inhabit climates that would have required intense effort just a few generations ago. Still, we carry with us the psychological preferences shaped by of generations of ancestors living in a much different world and often customize our environments to resemble that ancient habitat. Most of us prefer physical spaces that offer views of green vistas over windowless basements. Looking at trees might even have a real health benefit: patients who viewed trees outside their hospital window recovered more quickly12. The addition of trees and vegetation increases positive evaluations of built environments13. Indicators of harvest, such as fruit, budding flowers, and verdure, are favored over bare trees and impoverished fields.

Research suggests a relationship between stress and uncultivated outdoor settings. When placed in uncertain and stressful situations, individuals who viewed pictures of nature scenery showed less physiological distress14. Even passively viewing vegetation through a window can produce positive effects. Studies in biophilic design show that people living and working in spaces with vegetation compared to those without vegetation show improved performance on mental tasks, more positive moods, greater ability to re-focus attention, stress reduction, and diminished perceptions of pain in health care settings15.

Future research could revisit many of the studies above and examine the psychological outcomes when greenery is experienced in MR form.

The Dark Side

Despite the game-changing potential of spatial computing, the potent mix of artificial intelligence and mixed reality could lead to some terrifying outcomes. While this disruptive technology will make lives better in many ways, we need to think deeply about everything that can go wrong when people and machines become so interconnected. In addition to the obvious physiological complications that many will encounter (e.g., vertigo, disequilibrium, motion sickness), there are a host of pitfalls that must be navigated cautiously. Unregulated progress comes at a cost. If we adopt this technology too quickly, we may miss out on the chance to have useful discussions about the impact to privacy, health, safety, jobs, marketing overload, and isolation16.

How will we change under the influence of new technology? We are increasingly becoming reliant on our phones and computers to do and think for us. Soon there may be little need to store directions in your brain’s long-term memory. If everything is available on goggles you can just say, “take me to the public library.” You might not even need to look up the directions on a phone app. Our unbridled excitement about mobile MR technology could lead us into what psychologists call a social trap—a situation that carries obvious immediate benefits, but also hidden costs that emerge only later on. We will not know the consequences of many of these applications until they become more widespread, however, it may be too late at that point.

In a broad sense, the way we teach has remained the same since the time of the ancient Greeks17. A class listens to an instructor, some of the students ask questions, and a dialogue follows. This approach – employed in preschool settings all the way through continuing education workshops for skilled professionals – has been successful for many generations. In education, can we imagine a point where instructional headsets will replace teachers? In the context of social life, will some individuals end up preferring virtual friends and lovers over real ones? Quite possibly. If you can personalize a mixed reality hologram to match you specific physical, intellectual, and emotional desires what will that do to real relationships?

Conclusion

It is difficult to predict what Darwin, Allport, and Huxley would think of this emerging technology, but it certainly would not hurt to have multiple perspectives to help make sense of it. If technology prognosticators are correct, more people will be using headsets than handheld devices by 2025 and MR will be the digital lifeblood for billions of people. If this transformation seems impossibly fast, keep in mind that two of the top “revolutionary” ideas of TechCrunch 2006 were the BlackBerry Pearl and the iPod Shuffle—two devices that were mostly forgotten in less than a decade. Cities, like people, are becoming smart and responsive, and there is no reason to expect this trend will slow.

References

- Scoble, R. & Israel, S. (2017). The fourth transformation: How augmented reality and artificial intelligence change everything. Patrick Brewster Press.

- Vassos, E., Pedersen, C. B., Murray, R. M., Collier, D. A., & Lewis, C. M. (2012). Meta-analysis of the association of urbanicity with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(6), 1118-1123. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbs096

- Heinz, A., Deserno, L., & Reininghaus, U. (2013). Urbanicity, social adversity and psychosis.World Psychiatry, 12(3), 187-197. doi:10.1002/wps.20056

- Peen, J., Schoevers, R. A., Beekman, A. T., & Dekker, J. (2010). The current status of urban-rural differences in psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 121(2), 84-93. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01438.x

- Anderson, G. (2010) Loneliness among older adults: A national survey of adults 45+. American Association of Retired Persons.

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H.-Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Reduce Loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review : An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 15(3), 10.1177/1088868310377394. http://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377394

- House, J., Landis, K., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540-545. 10.1126/science.3399889

- Williams, J.B., Pang, D., Delgado, B., Kocherginsky, M., Tretiakova, M., Krausz, T., Pan, D., He, J., McClintock,MK, & Conzen, S.D. (2009). A Model of Gene-Environment Interaction Reveals Altered Mammary Gland Gene Expression and Increased Tumor Growth following Social Isolation. Cancer Prevention Research. DOI: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0238

- Zhong, C.B. & Leonardelli, G.J. (2008). Cold and lonely: Does social exclusion literally feel cold? Psychological Science, 19 (9), 838-842. doi/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02165.x

- Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420-421. doi:10.1126/science.6143402

- Gosling, S. D., Gifford, R., & McCunn, L. (2013). The selection, creation, and perception of interior spaces: An environmental psychology approach. In G. Brooker & L. Weinthal (Eds.), The Handbook of Interior Architecture and Design (pp. 278-290). Oxford, UK: Berg.

- Gosling, S. D., Ko, S. J., Mannarelli, T., & Morris, M. E. (2002). A Room with a cue: Judgments of personality based on offices and bedrooms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 379-398.

- Ulrich, R.S. (1983). Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In I. Altman & J. Wohlwill (Eds.), Human behavior and environment, Vo1.6: Behavior and natural environment. New York: Plenum, 85-1 25.

- Ulrich, R. S. (1986). Human responses to vegetation and landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning, 13, 29-44. doi:10.1016/0169-2046(86)90005-8

- Kellert, S. R., Heerwagen, J., & Mador, M. (2008). Biophilic design: The theory, science, and practice of bringing buildings to life. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley.

- Bennett, K., Gualtieri, T., & Kazmierczyk, B. (2018). Undoing solitary urban design: A review of risk factors and mental health outcomes associated with living in social isolation. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health, 4:7.

- Bennett, K. L. (2004). How to start teaching a tough course: Dry organization vs.excitement on the first day of class. College Teaching, 52, 106.