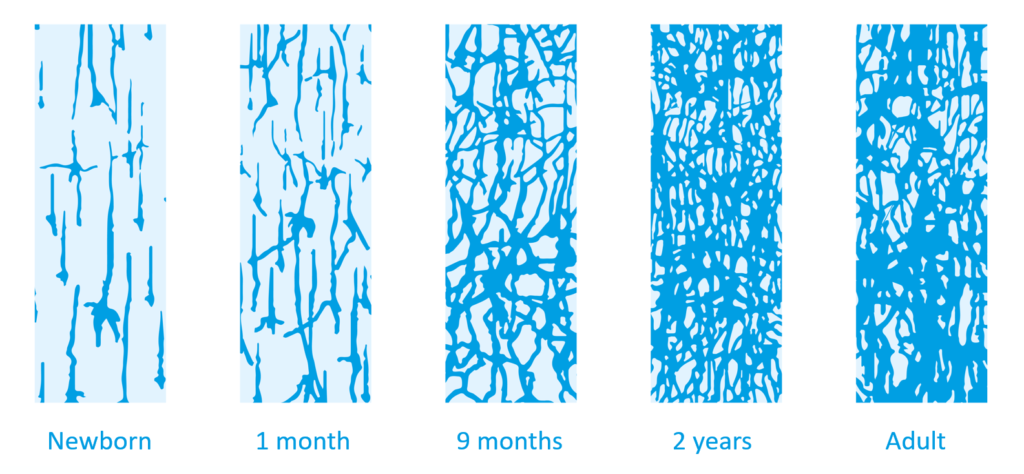

1 billion children are currently growing up in cities, of which an estimated 380 million are under 5 years old.1 Around 1 million neural connections are formed every second in a young child’s brain.2 This means an incredibly high amount (roughly 380 trillion) of new neural connections happen in the brains of babies and toddlers across cities around the world.

These neural connections are shaped by:

- The quantity, frequency and duration of warm, stimulating and responsive interactions between caregivers – most often parents – and young children

- The quality of the immediate environment in which they take place

- The quality of urban spaces influences babies’ and toddlers’ development directly by shaping their spatial experiences, and indirectly by modulating the quantity, frequency and duration of child-caregiver interactions in cities.

Urban planners, designers, managers, decision-makers and all those involved in the maintenance, upkeep and usage of urban environments are brain builders too, and can support caregivers in giving urban babies and toddlers the best chances in life.

Scientists, public health specialists and economists alike are unequivocal: babies and toddlers are the best learners on the planet, growing and learning fastest before their fifth birthday. During this window, their brains develop more quickly than at any other time of life, and their experiences carry a profound, lasting impact on their physical and mental health and their capacity to learn and relate to others.

The most powerful influencers on child development: parents and other caregivers.

What parents and other caregivers do during this time helps to build the brain architecture that lays the foundation for good health and learning in later childhood and adulthood. A baby or toddler’s relationships with the adults in their life are the most important influences on their development. These relationships begin at home, with parents and other family members, such as grandparents and siblings, and then extend outside the home onto the street, the neighbourhood, and the wider city.

Caregivers are responsible for a child’s safety and health, as well as what they eat and how they perceive the world. When parents and other caregivers talk, sing and play with their babies, they help to build a healthy brain wired to learn and interact with others. Studies show that warm, stimulating, responsive caregiving is one of the best predictors that children will do well in school, and be happy and healthy adults.

Urban environments shape brain-building.

Urban planning and design that incorporates the experience of babies, toddlers and their caregivers helps children thrive and empowers caregivers; it also carries benefits for other members of a city’s population characterised by limited range and unhurried pace, such as disabled and elderly people. Family-centred urban planning and design is not only about building more playgrounds. Families are disproportionately challenged by poor public transport, as well as food, healthcare and childcare ‘deserts’.

- Families with babies and toddlers typically need to access more services such as childcare or healthcare, and more frequently than most other residents.

- Access to nature and play opportunities are crucial to the development of children and the well-being of caregivers.

- The mobility range of caregivers with young children is restricted by their slower pace, their need for more space on transit and on sidewalks, and the necessity to pause and rest more frequently.

- Caregivers tend to rely on support networks for caregiving – formal such as childcare, or informal such as grandparents or neighbours.

- Caregiver mental health plays a key role in the healthy development of their children, as it impacts their ability to provide warm, stimulating and responsive care.

Such a recognition of the spatial experience of caregivers with babies and toddlers rests on the shoulders of the socio-ecological model of human development3 which places the healthy development of the child within its larger context (household, education, policies and cultural norms). This model can be applied spatially to understand how the larger environment in which babies and toddlers grow-up influences their development.

What does the city look like for a toddler?

If we adopt the perspective of toddlers and their caregivers – which can be done in various ways from playful workshops to more rigorous spatial assessment – we notice that their experience of the urban environment can be radically different than for adults.4

For example:

- The smallest features, such as a step or a pattern of tiles on the sidewalk, invite play and exploration.

- Young children depend on their caregivers to move around the city. Making it easier and faster for families with strollers and on little legs to reach key destinations is one of the best things cities can do to ease stress and make it more likely that those families will make use of services.

- Travelling long distances between well-baby clinics, maternal health services, childcare, green spaces and places to buy healthy food can be especially difficult – and expensive. Toddlers’ shorter height places them consistently close to passing car exhaust fumes.

- Waiting (for buses, appointments and in queues) is a challenge. Designing features that allow for exploration and play make waiting easier and create valuable opportunities for learning and interaction.

Combining empathy and data to achieve change

Understanding and experiencing the city as a toddler or a caregiver help us empathise with them. Combining this empathy with data and evidence on how urban environments affect babies and toddlers helps us identify the concrete opportunities of urban design to act as a powerful brain-building tool, and is core to initiate and sustain positive change in the way we design, plan and manage our cities.

References

- 1 Growing Cities. (2019, January 10). Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://childfriendlycities.org/growing-cities/

- 2 InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development. (2020, July 27). Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://developingchild.harvardf.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/

- 3 Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge – Mass. & London: Harvard University Press.

- 4 Empathy tools for urban leaders and designers. (2019, December 02). Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://bernardvanleer.org/blog/empathy-tools-for-urban-leaders-and-designers/

- 1 Growing Cities. (2019, January 10). Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://childfriendlycities.org/growing-cities/

- 2 InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development. (2020, July 27). Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://developingchild.harvardf.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/

- 3 Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge – Mass. & London: Harvard University Press.

- 4 Empathy tools for urban leaders and designers. (2019, December 02). Retrieved October 09, 2020, from https://bernardvanleer.org/blog/empathy-tools-for-urban-leaders-and-designers/