Answer intuitively: How far is far? How near is near?

The quantifiable answer might vary greatly from person to person, but when described through qualitative experience, the response would be nearly identical: close is anything immediately reachable, far is anything that takes time to get to. Even at the furthest extremes – from the minute individualism of user interface to top-down urban planning – time is the governing factor of our understanding of scale and proximity.

The Augmented City is one that is enhanced and expanded by the integration of technology, implying there is a symbiosis between what exists and what is perceived. Augmented reality (AR) technologies layer information upon our understanding of the real-world in real-time through computer-generated inputs such as audio, visual or GPS data. Thus, the augmentation of a city comes in many forms.

In the first layer, enhanced transportation systems could be seen as augmenting travel time, increasing the speed of pedestrian travel. The concept of a city’s edges can be derived from the extents of reasonable travel time a citizen is willing and able to go to reach the furthest ranges of their community. The use of AR technologies creates an additional expansion of a sensation of space and social connection, bringing things closer together — literally to our fingertips. With a tactile customised interface designed with the needs of each individual in mind, we can forge a better relationship to the Augmented City.

The scale of social media

In his non-fiction book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Malcolm Gladwell makes his case for intuition. He writes that often the decisions made instinctively are the same decisions we would make after thorough investigation and weighing pros and cons. Through inherent exploration of this concept through social media, current data on technology based communications have tested the ideas of attention span and information processing. Over time, the demand for instantaneous information has increased as the amount of time spent on any one idea has decreased. In this age of limitless information, we have cultivated a generation of individuals who are constantly making and committing to their intuitive decision-making skills. Simple gestures manifest these instinctive decisions into trackable data: double-tap to like a photo, swipe right to romantically match, press one button to share information. These interactions represent the types of “thinking without thinking” that Gladwell identifies, suggesting that the decisions are made so quickly that if asked to explain the thought process behind those decisions, it would take the thinker longer to invent a justification than it would to pass the original judgement itself. Though this may seem like a sign of complacency, this shorter focus on one piece of information could be a sign of a collectively higher emotional intelligence in becoming more comfortable with the powers of snap decision-making skills.1

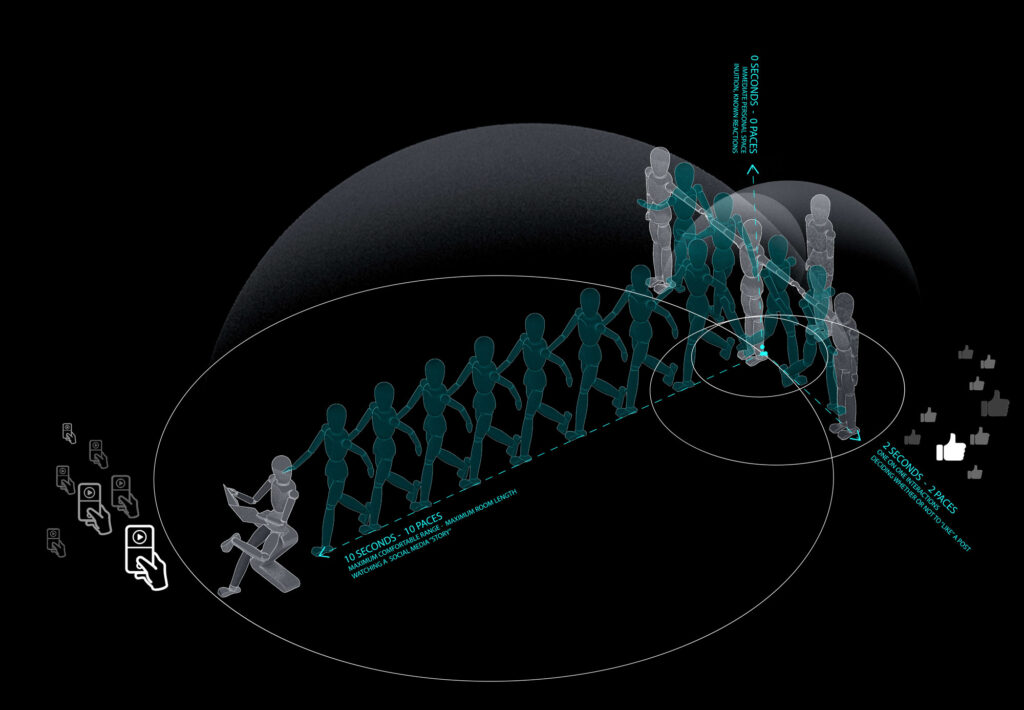

Social media gives us a direct insight into intuitive attention spans. As such, personal decisions that do not affect others are instantaneous, while deciding an opinion (such as liking a photo) about another person about two seconds.2 If we care to receive information of a friend we care about or person we follow, we have the attention watch a fragment of their lives (such as in social media stories) for a maximum of 15 seconds to understand where they are, how they feel, what they are doing and how we personally feel about all of that.3 Scientific information is presented in twenty minutes or less.4

These ideas of attention span can give us an understanding of what time span we are willing to comfortably dedicate to various types of interactions such as intimate, personal, social or public.

Intimate closeness or something we consider “personal” is something that is instantaneous accessible.This relationship of arm’s length where one needs no travel time to interact with any objects in the perimeter. We understand space for interaction as the time it takes for one to move from their personal space towards the personal space of another. If we relate that to the two seconds of time we allow ourselves to formulate an opinion of another person, that is about the travel time we are comfortable to put in to interact with them. According to the Attention Spans report by Consumer Insights of Microsoft Canada, the average person in 2017 has an 8 second attention span. When projecting this time across a walking-distance travel time, this may equate to about 8 paces at 31.2 inches per step. This would total to a length of 20.8 feet, the maximum distance for comfortable closeness for the human of average size and ability.

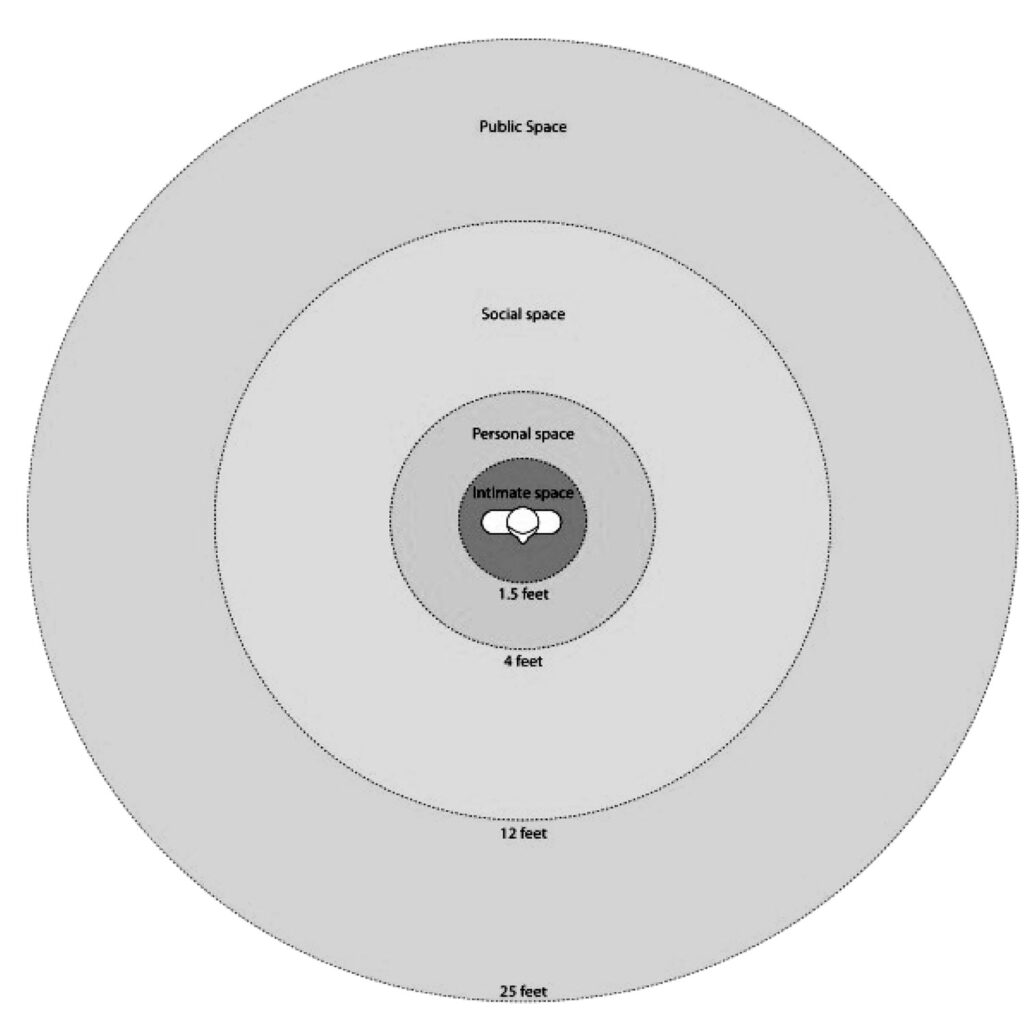

In Edward T. Hall’s Proxemics Theory [Figure 2], he ascribes the difference between private and social space through units of length. These measurements are based on an optimistic average for human interaction, not taking into consideration about one-third of the population that lies at the extremes of a bell curve. If this same theory of proxemics is seen through the understanding of time as a measure of distance, we may be able to create a more inclusive understanding of what is comfortable as scalable to the individual. This has already been an accepted principle in some instances of our built world, as in in the case of preschool classrooms that are scaled to fit for children whose paces and arm spans are smaller. It is critical to speak in these terms to allow for a parametric quality to the understanding of proportion.

Children, adults, and people with disabilities experience space differently. With technology that is easily adaptable, we can aspire to create interfaces and experiences that are compatible with everyone’s needs and abilities instead of an idealised form.

The augmented city

This idea of time as related to distance has always been an acceptable way of defining space on both a personal and social level. The 21st-century ideals of five and ten-minute walking radii have been integrated into the language for New Urbanism, a movement by architects to increase walkability and density in cities. However, the transformative qualities of technology to augment the way we experience our daily lives and cities had not [yet] been incorporated into this narrative. Unlike the physically ridged cities we must construct benefiting humans of average ability and size, the Augmented City is flexible — completely customisable to the needs of the individual.

To accomplish this, we may be able to design a more conscious city through the layering of AR over the existing conditions. In that spirit of possibility, imagine this Augmented City:

The mid-afternoon sprint at the office is often the most chaotic, after settling into the workday emails and notifications come flying into your field of view as you walk from one meeting to the next. Your periphery notification system is all aglow with information. If you dare dart your eyes to the left, you see the calendar notifications that you ought to leave within five minutes to take your child to their dance class. Look to the right and you’ll see that you must respond to the contractors for a request for information about their confusion on some 3D printed penalisation you specified. You stop dead in your tracks mid-corridor and open the projected model of the building. It appears in ghosted view hovering in the palm of your hand. You wait impatiently as you watch it zoom from the exterior to the minuscule issue in question. The panel was rotated by some construction worker. You push your fingers through the frame of the structure and hold the element to correct the orientation, swiping it away to send it back. As you reach for the door to your next meeting you realise your priorities lie elsewhere and you take to the streets to the nearest metro station.

Your advertisement settings are minimal and artistic in nature. The latest contemporary paintings appear in place of billboards and certain boutiques and cafes appear illuminated as you pass them implying that you would give these places a five-star rating based on your preferences. Once in the metro, you check back in with your meeting at the office. You see the other architects around you and engage in conversation as sounds of the subway are muted around you. Once you slow to your stop, the application closes, and you find yourself at your child’s school.

You love to watch the children play, their orbs of creativity bobbing around them and melding together the moment they decided to interact. Her daughter’s orb is often a collection of space-dust, butterflies and small shuttles. They swirl around her and she reaches out to cause them to flutter more enthusiastically. She sends one of her little objects to another friend across the way, falling to the floor in a fit of giggles. As always, your daughter is thrilled to see you. She is just as enthusiastic about the dance class you are accompanying her to. At the studio, she steps into her training forms – glistening sculptures that she inhabits whose shape informs her of how she should move. She adores feeling like a piece of art, trailing her fingertips along the edges of the sparkling shape to move her hands through first and second position.

While you wait for her to finish her class, you decide to visit your mother in her assisted living facility across town. You see yourself in your mother’s room. She has chosen to fill her walls with dangling holograms of orchids and vines giving the feeling that you were in the middle of a greenhouse, with mother planted in her bed. She is so very pleased to see you and immediately starts waving frantically, summoning her various augmented knitting projects towards her from the places she had scattered them around the room. Your mother has 3D-knit a sweater for you, and she’d like you to try it on for size.

The Augmented City is a conscious city, one that may resolve technological advances in an intuitive human- centred way. Taking into consideration the diversity of human needs, we can design a scalable, parametric, beautiful urban experience for all.

References

- In when to Cooperate and when to compete: Emotional intelligence in interpersonal decision-making by Pablo Fernández-Berrocal, Natalio Extremera , Paulo N. Lopes , and Desireé Ruiz-Aranda – a correlation is established through scientific experiment between a higher speed of social decision making skills and high emotional intelligence.

- In First Impressions, Making Up Your Mind After a 100-Ms Exposure to a Face; authors Alexander Todorov and Janine Willis explain their case study experiments correlating duration of exposure to judgement time

- Maximum Instagram story length is 15 seconds, maximum Facebook story length is 10 seconds, maximum Snapchat story length is 10 seconds

- Ted talks are limited to 18 minutes by TED curator Chris Anderson who says that 18 minutes is “short enough to hold people’s attention, including on the internet, and precise enough to be taken seriously. But it’s also long enough to say something that matters.”

- Identified as correlated to human kinesthetic interaction in Edward T. Hall’s, The Hidden Dimension, Chapter: Perception of Space; Immediate Receptors – Skin and Muscles; page 54. And defined in Chapter: Distance in Man, page 117.

- Defined in Edward T. Hall’s, The Hidden Dimension, in Chapter: Distance in Man, page 121

- The American College of Sports Medicine reports that the average step length is 2.6 feet or about 31 inches.

- Distance as defined by the limits of “public closeness” in Edward T. Hall’s, The Hidden Dimension, “Chart Showing the Interplay of Distant and Immediate Receptors in Proxemic Projection,” page 126

- Graphic representation in Edward T. Hall’s, The Hidden Dimension, “Chart Showing the Interplay of Distant and Immediate Receptors in Proxemic Projection,” page 126

- This parametric definitions of walking radii can be found in Duany Plater-Zyberk & Co’s Lexicon for New Urbanism, Chapter 2: Regional Structure