Photography changes our experience and perception of the built environment, argues freelance photographer and curator Alexandre Kurek. But does it play a role in changing cities for the better? And how might new imaging technologies using A.I. change that?

Alexandre Kurek is a freelance photographer and founder and editor of <allcitiesarebeautiful.com> — a community-driven platform for contemporary documentary photography and thoughtful writing, which provides an extensive catalog of artists, authors, and international publishers, as well as various resources for photographic research, inspiration, and progression. Alexandre lives, works and studies in Berlin. His work can also be found at @allcitiesarebeautiful on Instagram

Mark Bessoudo is an urban sustainability researcher, Member Chartered Building Engineer (C.Build E MCABE) and Fellow with the Centre for Conscious Design. He is based in London.

Photo: Charlotte Schreiber

Mark Bessoudo: Tell me a bit about yourself and your background. What inspired you to explore architecture and photography?

Alexandre Kurek: I was born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo but grew up in a small town in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, and have been living in Berlin for the past 12 years. I worked as a freelance fashion and documentary photographer for about a decade but then decided to focus on media studies and a more artistic approach to photography. I’m currently studying European Media Science at the Faculty of Arts and Media at the University of Potsdam.

My inspiration for exploring architecture and photography actually started with skateboarding. It was through skateboarding that I first found a keen interest in certain kinds of art, music and photography, and in exploring new parts of the city. Skateboarding had a huge influence on my perception of, and interaction with, architecture in a broader sense. It forced me to be more attentive and observant of the built environment around me. Ultimately, it’s what led me to start exploring my surroundings, taking pictures of things that caught my attention—which were mostly buildings and other artifacts of human intervention.

MB: Your blog serves as an influential platform and community showcasing the work of urban and architectural photographers from across the world. How did you start the blog and how has it evolved from being a platform for your own work to showcasing the work of others?

AK: Around 2010, when I was living in Düsseldorf and working as a freelance photographer, I started the habit of taking early morning walks with my camera. At first I would explore and photograph the neighborhood where I was living, but later expanded into other parts of the city.

“photography enables us to ask questions about places we would otherwise not be able to ask, or even think of asking”

The first iteration of <allcitiesarebeautiful.com> was intended as an online repository for all of the photographs I took during my morning walks and later on my travels. But the archive quickly grew, as did the number of subscribers. I was contacted by like-minded people from all over the world and began meeting a great deal of people who were interested in the same kind of photography.

This made me wonder whether I should also start showcasing other people’s work on my blog. I thought it would be a good idea to not only introduce artists and photographers to one another through their work but also to create an archive of the works I enjoyed most myself. It was around 2016 or 2017 when I put the first proper WordPress-based website version online, and allcitiesarebeautiful.com was born.

MB: The name <all cities are beautiful> is fun and endearing! How did you come up with it?

AK: One particular early morning walk, back when I was living in Düsseldorf, I noticed an interesting railway bridge near the main station and took some photos of it. On one of its pillars was written <all cities are beautiful> in stencil. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but photographed it anyway. It wasn’t until later, while sifting through all the photographs I had taken that day, that I looked more closely at that particular photograph and thought <all cities are beautiful> would make a great name for a blog that documented all the photographs I was compiling.

Funnily enough, the abbreviation for <all cities are beautiful> is ACAB—I like the idea of appropriating that derogatory term and turning it into something beautiful. Besides, with the amount of ACAB graffiti tags on structures in cities around the world, it could be considered as free marketing.

MB: I think the fact that you were attracted to this name in the first place, and later selected it as the name of your blog, seems to suggest that you have your own personal philosophy of what a city is, or at least what a city could be or should be. Were you being intentional with that? Is there a message that you’re trying to convey to your audience?

AK: I’m deeply fascinated by cities: their architecture, dimensions, the people inhabiting and shaping them: their infrastructures and politics; their surfaces, colors, patterns, and various light situations; their smell, noise, density. These all invoke a strong feeling of excitement in me. I enjoy roaming the street and being attentive and observant. I believe that the name <all cities are beautiful> encapsulates all of this joy and excitement towards cities, and people who share the same enthusiasm are naturally drawn to this project.

MB: There are many fields that many people would associate with city-building: architecture, engineering, policymaking, planning, urban design. I think fewer people would associate photography with it. What role do you think photography plays in our understanding of cities?

AK: First and foremost, I think that the ability to document something through photography — and thus enable us to archive those documents for, let’s say, further analysis and preservation — has had a major impact on our perception of cities. I know several architects and urban practitioners who explore urban environments with their cameras, seeking out, for example, certain perspectives, patterns, colors; some operate on a macro level, focusing on cityscapes, some operate on a micro level, focusing on details, and again, others (to whom I would consider myself belonging) focus on both and try to bring these two aspects together. Regardless, I think that those different perspectives and perceptions contribute a lot to shaping our fundamental understanding of cities and places in general.

MB: Do you think photography can change our perception of what a city is or what a city could be?

AK: There’s a significant difference between seeing something in a photograph and seeing it on a drawing board or in a rendering, for obvious reasons. Through photography, you can pinpoint and document specific intricacies as they develop over time. It also reveals or makes visible certain processes that would otherwise remain unseen. For example, since 2020, I’ve been documenting the construction of a multi-storey apartment building on the opposite side of my apartment. Watching its various stages of construction — from laying down the foundation to finishing up the roof and its facade — not only revealed how long such a construction could take but also who and how many people are involved in building it, and, to a certain degree, the infrastructure behind such a construction site.

Furthermore, combining the multiplicity of perceptions, perspectives, and realities of the changing nature of construction, maintenance and existence of the built environment allows others to experience cities in a very different way. It also allows people to experience cities in a way that they might not otherwise be able to. There are individuals among us who cannot travel to different cities or places as frequently as others, if at all. So in a way, photographs of places not only allow participation to some extent, they also enable us to create new or challenge existing narratives around these places. Consequently, photographs have the potential to alter, or at the very least, influence our perception of cities.

“We all bear a responsibility for our environment. Photographs that depict our surroundings possess the ability to remind us of that shared responsibility.”

MB: Beyond just perceptions, what role do you think photography can play in actually changing or reshaping the built environment?

AK: I am not a practicing architect or urban designer, but speaking from a phenomenological perspective, I think that photography enables us to ask questions about places we would otherwise not be able to ask, or even think of asking. It could be as simple as taking a photo of, let’s say, a strip of pavement, looking at it thoroughly and asking: what is it that I see? This one question could lead to a cascade of more questions: who constructed that pavement? What is it made of, and where did the resources for it come from? Does it look the same elsewhere? What are the underlying structures and politics constituting that pavement? I could think of a plethora of questions relating to just that one strip of pavement, which, in turn, would inevitably lead to questions regarding many other aspects of the built environment and its constituting or underlying structures.

MB: Many of the photographs you showcase on <allcitiesarebeautiful.com> evoke a particular aesthetic, and with that a certain type of message. To me, they speak to the tension between the beauty and banality of urbanization — the disparity that sometimes exists between aspirations and reality, or between the theoretical and the practical. I believe you called this aesthetic “anti-romantic” in one of your blog posts. This approach seems to be influenced by the The New Topographic Movement of the 1970s, which, you wrote, “not only provided an alternate image of the American landscape but also challenged viewers to consider the reality of human intervention in nature and the consequences of our own actions.” Can you comment more on this?

AK: I believe that, at least to some extent, we all bear a responsibility for our environment. Photographs that depict our surroundings possess the ability to remind us of that shared responsibility. That’s what the pioneers of The New Topographic Movement fundamentally accomplished with their work: through directing our gaze to what immediately surrounds us—towards something so obvious and so banal, most of us probably weren’t aware of it as something worth observing, let alone considered questioning it—they were able to remind us of our shared responsibility.

I think that their work, and subsequent artists who their work influenced, allowed us, over time, to develop a better understanding of our everyday surroundings, albeit not on a factual basis but rather on an artistic one. And that, to me, is a testament to the tradition of art and artists and their obligation towards society: gently steering us and guiding our attention in a certain direction.

MB: Speaking of having our attention guided in a certain direction, the question that I think is on everyone’s mind right now is how the advent of AI, specifically new image-generating tools (like Midjourney, DALL-E, or Stable Diffusion), will influence us. You could almost say that what these tools can generate is almost the opposite of the New Topographic Movement — rather than putting up a mirror to what is, it conjures up things that aren’t there, or things that can’t be. You could almost call it anti-anti-romantic (so, uh, romantic?) What’s your take on these new tools and their potential within urban and architectural photography?

AK: First of all, I think that AI image-generation is a great tool for conducting visual research into potential realities or what-if scenarios—something that photography cannot achieve, at least not to the same extent. When you think about it, photography can only transport visual information from the past into one’s present. AI image-generation, however, has the ability to do the exact opposite: it (virtually) creates a potential future and transports its visual information into your present, allowing you to visualize, let’s say, a future city or certain aspects of it, based on a currently existing one. That’s really exciting!

At the moment, I’m not sure about AI’s potential impact on archives such as allcitiesarebeautiful.com. But I’m sure of my interest in exploring its capabilities and collaborating with the people who are starting to use these tools in interesting ways.

MB: Have you seen these tools used in ways that you find interesting or beneficial?

AK: I would highlight the work of French photographer Olivier Campagne. I really enjoy Olivier’s output in terms of his vision and retro-futurist aesthetic. He creates artificial landscapes that are basically indistinguishable from existing ones. Of course, if you look closely and long enough, you can identify signs that what you are seeing is an AI-generated image, but at first glance: no chance. His images appear to be not far off from something that might exist somewhere or at some point in the future; they feel real in a sense. In my opinion, his work is a great example of how AI-generated images could influence the way we design and build cities in the future.

MB: Thank you for taking the time to speak with me. Your blog has become an indispensable source of inspiration for many people — more people than you probably realize. You’ve put a lot of time and effort into elevating the works of others, so I thought it would be nice to turn the spotlight on you for once. Thanks again for your contributions to the urban photography community — and more importantly, for reminding us that all cities are beautiful!

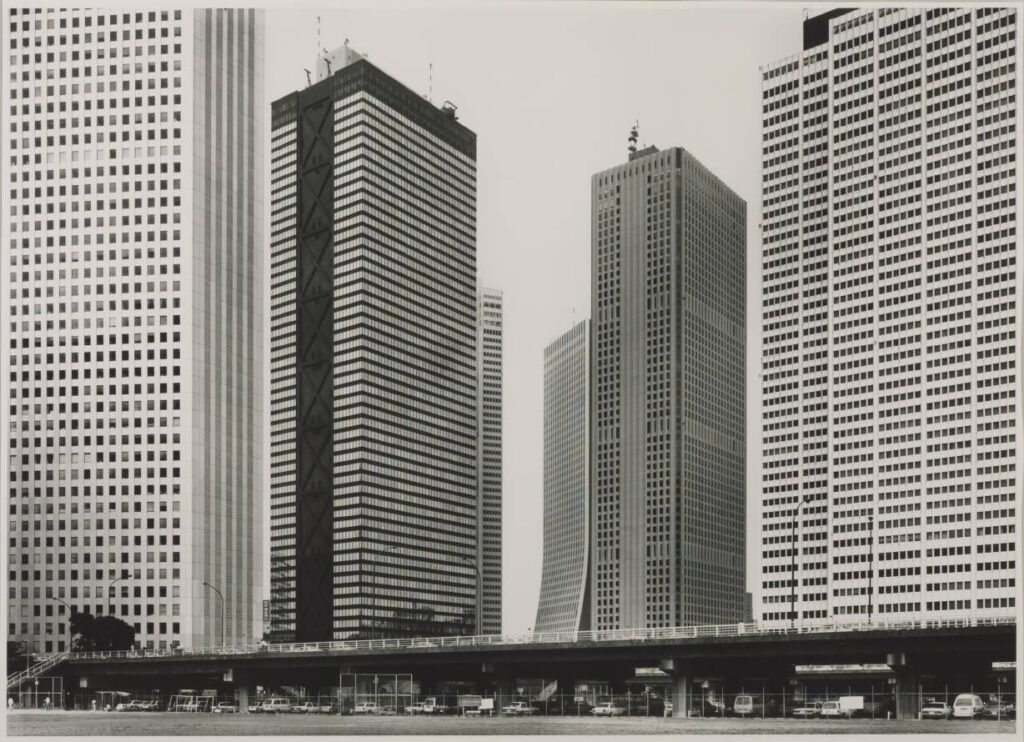

Opening photo: Preschelle Ann Bigueras, Dubai, UAE (2021)