ABSTRACT

Every day, we humans move within different (urban) spaces for different reasons. Thanks to digitalization and new technologies (such as micro-mobility), the society is worldwide more mobile than ever before. When we leave, we leave traces, both in ecological and socio-spatial terms, for example through the way we make contacts and connections in space. Next to our own mobility behavior, the means we use to move are decisive for what we perceive in our immediate environment. Do we walk to meet a friend, do we have to take the tram to get to our work or do we call an individual media to get to a meeting? The atmosphere and the shape of our built environment itself have a decisive influence on how we have learned to perceive and expect from a scenery. The connections between walking behavior and space use are complex and by no means obvious, but are rather based on social and cultural factors and vary from city to city. The site-specific context seems to be all the more important when it comes to questions of human mobility and localization, as each city follows its own rhythm of values and cultures, which now find themselves in the context of new, dynamically emerging references and globally determined factors. Climate change, strong urbanization processes as well as socio-spatial upheavals are increasingly influencing our mobility behavior in many different ways, both consciously and unconsciously. At the same time, due to Covid Pandemic, we can think more intensively about where we really want to be, but also in what way we want to move and perceive? Are we aware of the way we move and influence urban space?

#Human Mobility #Spatial Perception #Walking Behavior #Built Environment #Space Use #Mindset

THE WAY YOU MOVE IS THE WAY YOU PERCEIVE.

Architectural and mobility psychology teach us that movement is the prerequisite for perceiving space. To be able to perceive an (urban) environment, the human being has to move in it, because “perception is influenced by the movement from the very beginning, just as this is also influenced by the perception” according to the German architectural and mobility psychologist Flade (Flade, 2013, p. 32, translated by the author). To capture an environment approximately, comparatively many steps are necessary. Unlike an object, the environment is something that humans can only perceive by changing their location and perspective. As French philosopher Virilio (1978) noted: Images that merely pass by do not leave a profound impression. You only get this impression by actively moving in a space. He pointed out that “slowing down or even eliminating the dynamics of locomotion, fixing behavior and movement to the extreme, leads to serious disturbances in the human being and damages his ability to cope with reality” (cf. Virilio 1978, 38 f.).

The way we walk is decisive: Do we walk fast, do we walk slowly, do we walk with open eyes or are we even distracted by our mobile phone?

When we go faster, for example, the stronger the forward orientation would be, as once described by German philosopher Bollnow (1963). British architect Cullen (1961) stated that space can only be truly grasped at a moderate walking speed. He brought up the idea of “Serial Vision”, which means that people can experience a revelation of views while walking through an urban environment at it at a steady pace. In addition to our own walking behavior, it is important to what extent an urban environment provides the necessary atmosphere and framework to be able to move freely and perceive with confidence. What are the climatic conditions, how comfortable must a person feel to move in an environment (socio-spatially seen) and what are the physical conditions of the built environment – is there, for example, a pavement sufficiently available?

THE INTERRELATIONS OF HOW WE WALK – PERCEIVE AND – BUILD (URBAN) SPACE.

Historical influences, such as the events of the war or the turn towards a car-friendly city at that time, brought physical changes with them. New cityscapes were created, new impressions for the perceiver. The Swiss sociologist Lucius Burckhardt (1925-2003) examined the interrelations of how people move – how they perceive and – how they build and elevated this to the “Science of Strollology” in the 1980s. This was based on the thesis that an environment would be not perceptible, and if it were, then it would be based on visual representations that are formed and have already formed in the mind of the viewer. So, he raised the question – why is landscape beautiful? – to analyze what makes up the landscape to us humans (Burckhardt, 2015).

In doing so, Burckhardt investigated the circumstances how far the car-friendly city space had an effect on human walking and perceptual behavior. Thereby, he considered walking in the context of various forms of active mobility, such as cycling or the use of public transport. His multi-layered experiments in the course of his work, as a lecturer at the Department of Architecture at the University of Kassel, Germany, demonstrated to what extent humans are shaped by external circumstances and how often they unconsciously appropriate space in the same way over and over again. His aim was to appeal to space users and planners to consciously deal with the environment. He emphasized:

“Every individual who is quick has no eye for detail. Everyone sees what they he/she has learned to see” (cf. Burckhardt, 2017, p. 37).

Burckhardt brought it to the point by saying one must learn to perceive landscape. In doing so, he referred to all the trends (such as social media today, in his time it was holiday advertising) that tempt individuals to develop an idea of a place even before they have seen it. He pointed out, that magazines show us a picture of a landscape and how we assume it should be in reality. But these are only partial aspects of a landscape, because, whether urban or rural, landscapes also consist of “unattractive things” such as silo towers or industrial facilities, for example.

Austrian urban planner Camillo Sitte once put it:

”What counts is the position of a spectator and the position in which he is looking. Only that which a spectator can hold in view, what can be seen, is of artistic importance” (Sitte, 1889, p. 84, translated by the author).

Burckhardt expressed it with his drawing –

“The view of a city that we visit as strangers is mostly preformed. We focus on moments or specific sections as in a watercolor. We know these perspectives from numerous pictures as well as from film and television or from the Internet. In the case of the city of Rome, the Colosseum is part of it, as well as St. Peter’s Basilica… The real life and the simple houses of the local population elude the view of the tourists, who are exclusively eager to visit the well- known places again and again. It takes some discipline to turn one’s gaze away from an ancient statue and ask one- self what it was once aimed at and where it is turned to today. Perhaps the statue once looked at a park, now it looks at a construction site or a house” (Burckhardt, 2017, p. 380, translated by the author).

Architectural psychology points out that it depends on our own action plan whether we acquire a space and experience it positively. If, as simple example, a bench is as attractive in appearance as it is in position (e.g. in the countryside), this does not mean that a pedestrian notices it or even approach it. Human character traits and behavior, political and social circumstances, cultural context, timing, weather conditions, topography, and new emerging circumstances, such as Covid Pandemic, can prevent us from ever using the bench or even from visiting it more often.

Burckhardt expressed that human mobility and spatial perception are subject to historical and social conditions and embedded in all location-related artifacts and described it as follows –

“But it is precisely this that makes the social character of the meaning of landscape: that the statement lies not in the object under observation itself, but in its cultural interpretation, in the cultural spirit, through which we learn to see and understand the landscape” (Burckhardt, 2017, p. 49, translated by the author).

He critically questioned both urban planning interventions and the creation of ever new guidelines, as in his view these would be more of a “patchwork” than a conscious approach and sustainable urban planning. To this end, he raised the question of who was actually planning the planning and who should be entitled to intervene in the environment.

NEW CONTEXTUAL REFERENCES LEAD TO NEW DYNAMICS OF MOVEMENT AND NEW WAYS OF PERCEPTION

If we now transfer Burckhardt’s thoughts on walking and spatial perception to today, we consider them in the context of increasingly complex influencing factors. A prominent diagnosis of the present is that the accelerating dynamics of change in the globalized world has led to a higher complexity of (individual) everyday experience (1). Human mobility as well as new ways of living (due to factors such as demographic change, transnationality, de-localization of work) in the context of globalization processes, technological progress and digitalization influence not only the mobility of the individual themselves, but also physical urban structures, social networks and the content people perceive while walking. Accordingly, society is more mobile within different levels of action. The term “traffic behavior” was replaced by the term “mobility”, because the term “mobility” would trigger positive associations: “Being mobile means being lively, interested, open-minded, progressive, dynamic, successful and young” (cf. Flade, 2013, p. 24, translated by the author). Thereby, human mobility and spatial perception must be considered in the context of new modes of mobility, here the term micro mobility should be mentioned.

Micro mobility refers to the use of electronic scooters and bikes to travel shorter distances around cities, often to or from another mode of transportation (bus, train, or cars). Users typically rent such a scooter or a bike for a short period of time using an app.

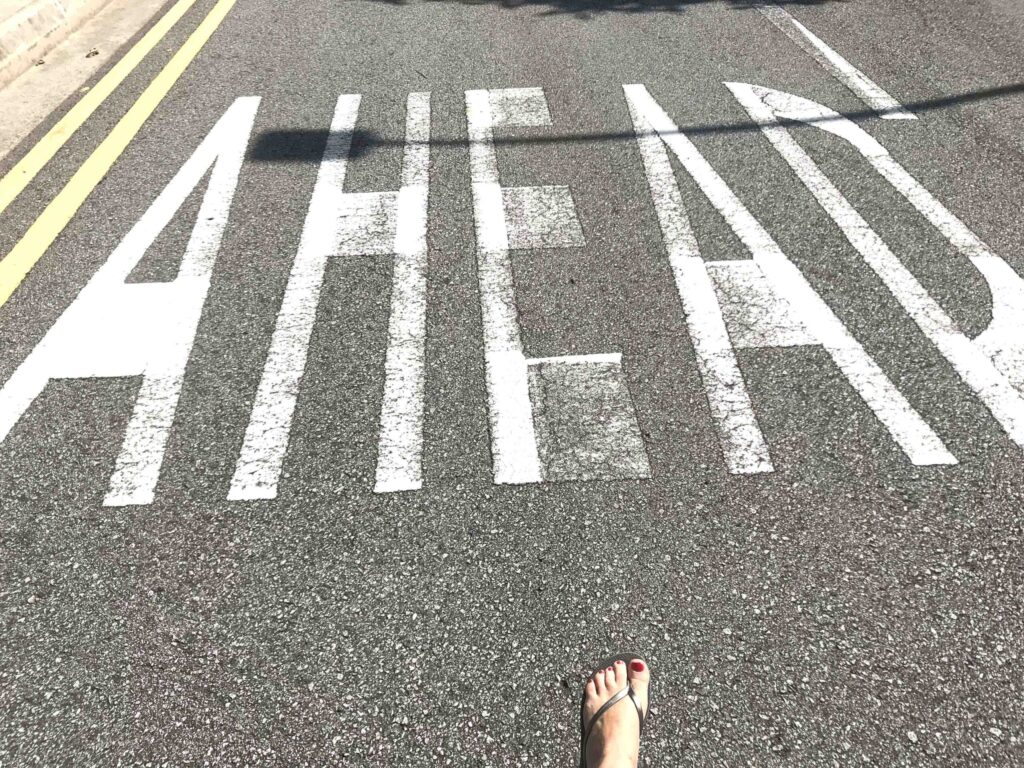

The German philosopher Schmitz speaks here of the fact that we live in a “modal temporal world” in “which some things are, some things are not yet and some things are no longer” (Schmitz, 2014, p. 111, translated by the author). The German sociologist Rosa further states out that globally seen the society would be “accelerated”, which would not only be shown in the mobility behavior of the individual, but also in the many activities and events that people experience. With acceleration in this sense, one now transports, communicates, produces etc. more and faster compared to the previous social epoch (cf. Rosa., 2016). Urban planning has also recognized this and averted the danger of overlapping activities, such as walking and mobile phone use (see next picture). But isn’t this red signal rather an indication of how externally controlled we are moving? It raises the question in which sphere we actually find ourselves when we move. What do we perceive from our immediate surroundings while walking?

(1) Attempts to characterize these developments of increasing complexity of the world were made, for example, in the 1990s with the acronym “VUCA”, which is composed of the words ‘volatile’, ‘uncertain’, ‘complex’, and ‘ambiguos’ (Johanson & Euchner, 2013). By definition, one feels insecure and disoriented in this “VUCA world” [sic].

HOW WILL WE WALK OUR CITIES IN THE FUTURE?

When we talk about future human mobility in urban traffic planning, the focus is often on local public transport and sustainable means of mobility. In terms of sustainable urban planning, the compact, coherent, coordinated future neighborhood represents a currently essential planning approach (Urban Nexus), where urban growth built around public transport can create cities that are economically more dynamic, healthier and with lower emissions.

The Urban NEXUS is an approach to the design of sustainable urban development solutions. The approach guides stakeholders to identify and pursue possible synergies between sectors, jurisdictions, and technical domains so as to increase institutional performance, optimize resource management, and services quality (ICLEI, Local Governments for Sustainability, 2020).

Singapore, for example, has been striving for the “Garden City” (1) goal for years, and many cities around the world aim for green urban structures, a health-supporting atmosphere, pedestrian friendly and worth living in. Walking and a healthy lifestyle are worldwide promoted issues. While human mobility and lifestyle needs can be directly integrated into the planning process (2) by creating new neighborhoods and even become a quality criterion of a new residential area, existing areas pose a challenge due to the given socio-spatial structure, where fundamental intensive planning interventions have to be balanced against “minimal design interventions” as the sociologist Lucius Burckhardt (cf. Burckhardt, 2013) once already put it. Here, the site-specific context seems to be all the more important with regard to questions of mobility and localization, as each city follows its own rhythm of values and cultures, which are now found in the context of new dynamically emerging references and globally conditioned influencing factors. There are general patterns of human mobility behavior city-wide, such as in Singapore the preferred walking within sheltered pavements due to tropical climate (cf. Erath et. 2015). The interrelationships between walking behavior and space use are however complex and not obvious at all, and are rather based on social and cultural factors, and differ from city to city.

This year, as part of my master’s thesis concerning human mobility and spatial perception in Singapore’s Public Housing Estates, I conducted a transdisciplinary study with young residents and urban planners (coming from different fields of action) inside sheltered walkways – deriving the urban futures. The young participants discussed about the way of thinking that motivates people or prevents them from moving and appropriating space. They reflected that it can be political restrictions that cause people not to appropriate and use a space in a meaningful way, and that it often simply persists in people’s minds, often without any reason, to continue to avoid an urban space. They further analyzed that it would be often extremely difficult for young people to question their own behavior and communicate their needs for example to the older generation. On the one hand, they often would lack urban retreat space for themselves, on the other hand, they would be often too lazy or simply lack the time to move around and to use their immediate outdoor space. Thanks to media like “Grab” (transport/food delivery), they would get from A to B quickly, but also would tend to move less actively. All participants in the study agreed that the way urban space is designed can make a decisive contribution to its use. In particular, the issue of the future world of work played a decisive role for them in terms of their mobility behavior and how they imagine the future walkway to be. In their eyes, this will have digital tools and a future-oriented appearance, just like the urban space in general. Their visions of the future path within their habitat were then called into question when the discourse about a sustainable implementation of their ideas began. It became clear that an attractive environment would be nothing without conscious human use and action, and vice versa. They pointed out that they had to become clear about the extent to which they really wanted to make their urban space accessible and usable, and that this can only be achieved through constant exchange and communication between old and young generation, between government and residents, – between all the stakeholders of the city.

(1) The term “Garden City” was introduced by Singapore´s Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in 1967. It means the vision” to transform Singapore into a city with abundant lush greenery and a clean environment in order to make life more pleasant for the people (Lee, 2000).

(2) Sustainable Mobility and Settlement Planning: Municipal decision-makers, providers of mobility services, civil society and research are brought together with the aim of developing implementation concepts for neighborhood design that enables sustainable mobility for residents, helps to reduce socio-ecological inequalities and improve the quality of life. This is the case, for example, in the real-life laboratory of “Lincoln” in Darmstadt, Germany, which was surveyed as part of the research project “QuartierMobil”, funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as part of the funding measure “Implementation of the lead initiative Zukunftsstadt”.

FUTURE HUMAN MOBILITY STARTS WITH THE CONSCIOUS HUMAN-SPACE RELATIONSHIP

The participants in my study were confronted with their human-space relationship and with the question of what a city on a human scale actually means to them – by consciously deriving an urban future vision in the here and now that can be sustainable and realizable in the long term. In fact, it is often quite unclear what kind of capabilities drive urban change towards sustainability, such as the disruption of current paths by profound and radical changes in existing urban structures, cultures and practices (Wolfram et al. 2019; Frantzeskaki et al. 2018). If we humans are now consciously concerned with our mobility behavior, we are concerned with our participation in urban events, with the habitat in which we act – on which we have an effect with our mobility behavior.

If society, globally seen, wants to move from the car-friendly to the humane city, we individuals must first examine our way of thinking and question what we really need in our immediate urban surroundings. And what we have to do individually to achieve this. It is about questioning one’s own mobility behavior and orienting it towards a common goal. Here, this new focus area Human Mobility will contribute to understanding the interrelationships, how we move – perceive and build urban space and discuss with you all as urban actors and space users which structural or human behavioral changes are necessary to create framework conditions for sustainable mobility and space appropriation. Burckhardt pleaded for “minimal design interventions” (cf. Burckhardt, 2013), which lead to a better understanding and awareness of space and sustainable action on the part of the space user. In terms of urban planning, he saw invisible design (cf. Burckhardt, 2012) rather than the essential design to be considered. He put it like this:

“Invisible design. This means today: the conventional design that a social function itself does not notice. But this could also mean: A design of tomorrow that is able to consciously consider invisible overall systems consisting of objects and interpersonal relationships” (Burckhardt, 2012, p. 117, translated by the author).

Invisible design was in Burckhardt´s eyes for example when the tram runs all night, that everyone has access to the city’s events. We will regard Future Human Mobility as Invisible Design, questioning what would conscious human mobility will be in your city – what will it mean for the residents of your neighborhood? Here, urban identity, site-specific movement patterns and rhythm, participation, marginalization, acceleration, alienation, new appropriation of the world, polarization processes, all these terms will play a decisive role when we talk about future human mobility as a conscious use of urban space.

The definition of future mobility should be understood as a transdisciplinary, practical field of research. We want to explicitly encourage experimental research and creative discourses on what exactly future human mobility in your city means and encourage to enter into a common discourse on what unites us as a global community in moving our urban spaces. Let’s exchange ideas.

REFERENCES

Bollnow, O. F. (1963). Mensch und Raum (Humans and Space), W. Kohlhammer Press, Stuttgart.

Burckhardt, L. (2017). Landschaftstheoretische Aquarelle und Spaziergangswissenschaft (Landscape-theoretical Aquarelles and Walking Science), Martin Schmitz press, Berlin.

Burckhardt, L. (2015). Why is landscape beautiful? – The Science of Strollology, Martin Schmitz Press, Berlin.

Burckhardt, L. (2013). Der kleinstmögliche Eingriff (The smallest possible intervention), Martin Schmitz Press, Berlin.

Burckhardt, L. (2012). Design is invisible – design, society and pedagogy, Martin Schmitz Press, Berlin.

Cullen, G. (1961). The Concise Townscape, Routledge, Abingdon.

Erath, A. L; van Eggermond, M. A. B.; Ordóñez Medina, S. A.; Axhausen, K. W. (2015). Modelling for walkability: Understanding pedestrians’ preferences in Singapore, IVT, ETH Zurich.

Flade, A. (2013). Der rastlose Mensch, Konzepte und Erkenntnisse der Mobilitätspsychologie (The restless human being, concepts and findings of mobility psychology), Springer Berlin, Heidelberg.

Frantzeskaki, N., Hölscher, K., Bach, M., Avelino, F. (2018). Co-creating sustainable urban futures – A primer on Transition Management in Cities, Springer Berlin, Heidelberg.

Rosa, H. (2016). Resonance – A Sociology of the Relationship to the World, Suhrkamp Press, Berlin.

Schmitz, H. (2014). Atmosphären (Atmospheres), Essay: Landschaft als Wahrnehmungsweise (Landscape As Perception), p. 111-133, Karl Alber Press, Freiburg.

Sitte, C. (1889). Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen (Urban planning according to its artistic principles), Carl Graesser Press, Vienna.

Virilio, P. (1978). Fahren, fahren, fahren… (Drive, drive, drive…), Sammlung früher Aufsätze Paul Virilios aus den Jahren 1975–1977 (Collection of early essays by Paul Virilio from the years 1975-1977), Berlin.

Wolfram, M.; Borgstroem, S.; Farrelly, M. (2019). Urban transformative capacity: From concept to practice. Ambio. 48. 1-12. 10.1007/s13280-019-01169-y.How Will We Walk Our Cities in The Future? The Contexts and Meaning of How We Walk – Perceive and Build (Urban) Space