Introduction

Cities are complex and hybrid beings. Due to their nature, there is no surprise to find out that we still do not fully understand them. Architects and professionals in urbanism alike, throughout history, have struggled to define the city. There are plenty of definitions out there but none of them are complete or uncontested due to their exclusion of the mind and brain. It seems as if those definitions reflect thoughts we can not fully grasp or understand. In spite of our lack of comprehension, we continue to design and make cities, with at best partially-conscious awareness of their causes, effects and consequences.

Nowadays, science is attempting to overcome our limited understanding of cities, and replace old (and obsolete) practices. Science is participating more and more in city design, generating experiments that help understand the reaction of people to a certain stimulus using different tools and technologies1. This progress is important but perhaps misleading since the complexity of the city is hard to grasp holistically. We must also address the problem of creating the conceptual framework to contextualise new findings.

It all starts with the mind

Cities are about experiences, and experiences relate to the mind. However, cities are designed in such a way that reveal our misunderstanding of the mind. We live in places often designed by people who barely understand the user, but why is that the case?

I argue that architects and professionals start designing and making cities with pre-existing beliefs extracted or inherited from other disciplines. Philosophy has greatly influenced architecture, even if it is not so obvious at first glance. Moreover, disciplines such as neuroscience and psychology hold sway in city design, but this is happening before we understand the nature of a city itself. As a result, they are both the source of enrichment and confusion in architecture and urbanism.

Philosophy of mind in particular has been a tour de force for architecture. This is evident when we put the words materialism, idealism and dualism in context. The first concept, materialism, relates to matter as the fundamental source of everything that exists. Applied to city design or architecture, materialism denies the mind and accepts only what is visible or tangible. Materialism embraces, just like science, only what the third-person view can say, state or measure, and therefore favours objectivity.

In opposition to materialism, we have idealism, which puts forward the idea that reality is a mental construction or immaterial. Applied to city design or architecture, idealism embraces the mind but relies heavily on subjectivity, or the first-person viewpoint. This is evident when we design relying on hunches or poorly-shaped intuition, or when we trust blindly in the narratives of people we are designing for.

It is often thought as a middle way, but dualism is not necessarily the conflation of both materialism and idealism. Dualism states that both mind and body exist and work together, but it eventually sets them apart by stating that it is possible to have a mind without a body. This causes the cartesian anxiety, the obnoxious feeling that we get due to our separating what is in fact, an unity. Dualism does not work either, when we apply it to architecture or city design, because mind and body are treated as separated entities, with little communication between both of them. We have first and third person experiences available but there is no proper interface.

As a product of our beliefs, the designing and making of cities suffer. The three positions mentioned are symptomatic of the confusion within architecture and urbanism. Architects and professionals alike do not seem to agree on which road to take, and therefore have no option but to base decisions on intuition. As a consequence, we either perpetuate the extreme views of the world, or we languish in the cartesian anxiety2.

It appears as if the best we can do is accept the presence of opposites, –mind and matter (and its derivatives)– but without serious hope of understanding nor mediating their differences. This is what I will call the explanatory gap3, which in the philosophy of mind refers to the difficulty to explain how physical properties give rise to non-physical elements, such as the mind or consciousness. Here, I use the term in that sense (i.e. how physical elements such as architecture, give rise to changes in our mind), but not exclusively, since I argue that the relationship between mind and matter is reciprocal and circular.

Embracing complexity

To recap the main ideas:

- in spite of having trouble understanding cities, we continue to design and make them,

- pre-existing beliefs inherited from other disciplines affect how we stand when asked about the mind and its relation with the physical, and

- our position on the mind determines, somehow, the kind of cities we design and have.

The explanatory gap, or the problem of the mind and its relation with the physical has great influence and impact in city design. I argue that it proposes a dramatic reconceptualization of the city through transdisciplinary work and requires the creation of a metalanguage. In order to solve the explanatory gap in city design we must embrace complexity. This means learning to work with apparent contradictions and opposites –such as the material and immaterial, the objective and subjective, first person views and third person views–, without fear of crossing boundaries outside of our disciplines. Embracing complexity in city design is accepting opposites that may also complement each other.

Therefore, the solution urges us to let go of both our cartesian anxiety and the inherited views of the world we hold onto (materialism or idealism) in favor of a middle way that helps architects create cities without neglecting the mind-body-environment relationship. Such middle way may not come easy, as the ideas that come next will show a radical departure from how we often think of architecture and the city.

A new conceptual framework for city design

To understand the true nature of the city we must embrace mind and matter, but not the way dualism and design practices do. Dualism accepted mind and body, but it never managed to propose a way for both worlds to communicate properly. On the other hand, materialism denied the mind, and idealism empowered the mind without much evidence or support.

The following are steps working to unveil the role of the mind, its interaction with matter, and the purpose of relating it to city design. The main and fundamental premise is that cities exist only because experience exists. It might seem a given, but it is imperative to understand cities as functions of the experiences that designers create for agents (e.g. conscious beings) who live in a city. Cities are not only the physical elements, but actually they are a world of possibilities where genuine experiences can be created, with or without awareness of their consequences. When a city is created, several experiences, predicted or not by the designers, are created as well. I argue that this fundamental premise must be present in the definition of a city.

A city is the space of experiences, but how do we actually experience a city? An experience is something that we live through our bodies. Our brain may be important to process all stimulus but it is not the only feature that makes an experience possible. In fact, it is our body, first and foremost, that helps any agent to experience something. Our body is situated in a space and therefore react specifically to a stimulus from the environment (i.e. architecture, cities, nature, etc). Without a body, no processing is possible. It plays such an important role beyond the brain in cognitive processing, that we can argue that our body is an extension of our mind, or even further, it is embodied cognition.

There is no agent without environment and there is no environment without agent4. We have bodies, but they are situated in an environment, which also plays an important role in our experience. Just like we need a body to experience something because the mind or brain can not do it on their own, we also need an environment, a source from where we can receive an experience.

The agent and environment interact with each other and constrain mutually. If we accept that as a fact, we should ask: is the environment something that already exists or is it something that we, agents, create? We tend to believe that reality is out there and that our senses do their to best to represent it. A better description would be that the agent and the environment both shape our perception. The environment shapes our mind, and in return, our mind shapes the way we perceive the environment. We can say that in the process, we create the world again and again, that is, we enact our world constantly, we construct the experienced perceived environment5.

Still, we need to make one more step which conveys an idea that is hardest to accept. What if our mind extended into the environment? We first explored how the mind does not occupy only our brain, but extends into our body. Provided that our body participates in cognitive processing we accept it as an extension of our mind. Our body is a physical entity and so it is our environment, so it is conceivable that the environment can be the extension of our mind as well. Following Andy Clark, we can argue that our environment could be an extension of our mind if it developed cognitive processing capabilities in our brain6. Technology is a good example: our cellphones often replace our memory storing data we used to retain in our brain. The same role applies to cities, buildings, public spaces, etc. Any landscape could be an extension of our mind since it retains and activates memories.

The relationship between the environment and the agent attests that our mind needs a body, and our body needs an environment. Therefore, we have an unbreakable structure; mind-body-environment, where each of the elements constrain and enhance the others. Science must simplify the complexity of this structure in order to study it. However, the separation of elements that are so bound reduces our chances of reaching valuable understandings. All of these elements work within the logic of autopoiesis, which means that the relationship between them is recursive, circular and reciprocal7. Autopoiesis is at the core of the foundations of complexity, and thus, it is present in cities, helping relate apparent opposites that at the same time, complement each other.

The importance of the mind-body-environment relationship, or mind-body-cities, is evident through the revision of the concepts and ideas in this part of the paper. Before moving on, let’s review them:

- Cities exist only because experiences exist as well.

- We experience the cities through our bodies, which work as extensions of our minds.

- We enact our world, that is, we create the experienced perceived environment.

- Our mind extends into the environment only if it takes part in our cognitive processing.

- Autopoiesis rules the relationship between mind, body and environment.

Embracing the mind through the five premises above will allow architects and professionals in urbanism to gain a new perspective on the nature of the city. However, this new conceptual framework gives rise to a new problem, the problem of language.

The problem of language

Solutions to technical problems, no matter what kind of technology we use, never suffices in solving the conceptual problems. Recent experiments that try to understand certain reactions of agents under particular stimulus only succeed in very controlled conditions and do not reflect the intricate nature of the city.

The framework previously described forces us to see cities under new lenses, allowing professionals in urbanism to work beyond the capacities and restrictions of a particular or individual discipline, but yet, in cohesion and unison. These are the lenses of transdisciplinarity8.

To acknowledge transdisciplinarity, we must embrace, recognize and surpass the distinctiveness of every discipline. Different disciplines practice different methodologies and use different tools. For the purpose of this paper, I will focus on only one difference, that which exists between hard and soft sciences. It is an important distinction since hard sciences rely on a third-person viewpoint, while the soft sciences work within a first-person viewpoint.

This difference, from those two perspectives, the external and the personal, is the one which challenges our understanding of the complexity of the city. It posits the difference between materialism and idealism, and it also marks the opposition and complementarity of several pair of concepts such as objectivity-subjectivity, material-immaterial, physical-non physical.

Such differences between those pair of concepts make communication between disciplines very difficult and thus our comprehension of the city suffers. To solve such a problem we must create an interface between the hard and soft sciences. As David Harvey put it, we must build a bridge between sociological and geographical imagination to understand the city and then solve its problems9.

Such a bridge is a metalanguage that accepts city design as a scientific endeavor that favours transdisciplinarity, working to create cities and predict their outcomes. However, if city design aspires to be complete in all possible ways, it must welcome the science of experience. That means it must work with both the third-person and first-person view in a disciplined and structured manner.

Neurophenomenology is the solution proposed by Francisco Varela as a remedy for the hard problem in philosophy of mind10. However, it applies as well in architecture and city design, or any other discipline that requires a scientific study of experience, since the mind and brain are present one way or another. Neurophenomenology proposes a non-reductive way to study experience: it takes seriously the narratives of people, first-person reports (phenomenology) and confronts the results with those obtained by neuroscience.

How do we take such narratives seriously if they come from the first-person view and thus, are biased and subjective? Varela suggests that we can train people to give reports appropriately, with results that are more objective and closer to the truth. Nevertheless, Varela states that neither neuroscience nor phenomenology are capable of evaluating experience on their own. First-person sciences and third-person sciences need to validate one another.

But even if the first person narrative or data is deemed more valid, we are faced with a difficult challenge: how can we integrate both worlds (sociological imagination/first-person viewpoint/subjective) and geographical imagination/third-person viewpoint/objective) in an unified language that every discipline can understand?

Building the bridge

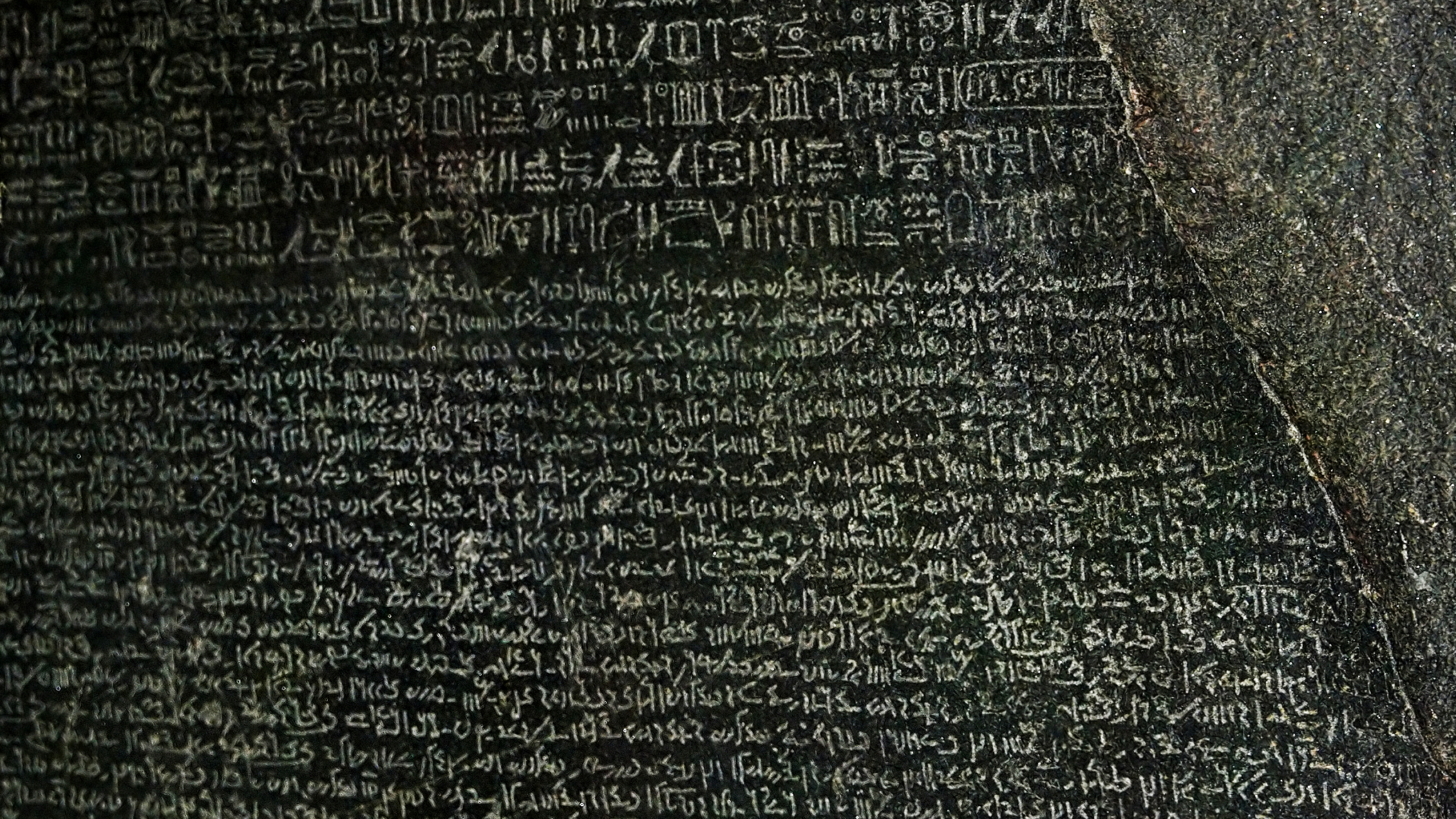

The search for a universal language has been, and still is, a very difficult one. In fact, city design and architecture should not avoid it if they aspire to understand the city. The key effort to build the bridge suggested by Harvey resides in translating the components of the city and architecture into a language that, in opposition to the one humans use, is not ambiguous or subjective.

For the purpose of this paper, I claim that information is the lingua franca that we need to in order to create better cities and predict their outcomes. Since this is new territory, it is necessary to defineinformation as “the act of informing, where both sender and receiver shape each other in the process. Information is a quantity that can be understood mathematically and physically. Moreover, any material object is an informational structure, from where information can be extracted.”11

The creation of this metalanguage through information implies the conversion of both geographical imagination and sociological imagination to informational structures. The first one is conceivable since it relates to hard and objective sciences, but the second remains hard to fathom, due to the subjective nature of the soft sciences.

In spite of the difficulties, the conversion must take place. The idea of this metalanguage is to create an equation of sorts that allow for variables to play in unison and somehow predict, either the spatial or mental state for a specific experience.

It starts with neurophenomenology. Since phenomenology and neuroscience use different languages, Varela recommends contrasting one with the other to validate the results that either discipline obtains. However, I argue that this does not suffice: to convey and understand appropriately the reports produced through phenomenology, so as to identify a particular perception or emotion whenever it arises, we must synthesise results and give them empirical value. Centuries ago, Gottfried Leibniz anticipated this and argued that

“if we could find characters or signs suited for expressing all our thoughts as clearly and as exactly as arithmetic expresses numbers or geometry expresses lines, we could do in all matters insofar as they are subject to reasoning all that we can do in arithmetic and geometry. For all investigations which depend on reasoning would be carried out by transposing these characters and by a species of calculus.”12

Leibniz’s proposal was not possible in the 18th century, but the development of neurophenomenology and several other disciplines may allow the resurgence of his characteristica universalis13. It could create a vocabulary that resembles a universal language for mental states, making the relation between experience and brain activity more succinct. I argue that neuroscience has progressed enough to intersect effectively with phenomenology.

Phenomenology could benefit from the characteristica universalis, turning reports into empirical data. In this context, ideas such as Gaston Bachelard’s Topoanalysis14, could revive and help understand the connection between emotions and space. The task of neuroscience seems easier since the translation of brain activity into mathematics is already in progress.

One more conversion will need to take place which represents the variables of space: the configuration of the city or architecture, into a complimentary language to that of phenomenology and neuroscience.

As a consequence of applying this metalanguage, appropriately based on the new conceptual framework, cities will possess the quality without name which Christopher Alexander envisioned. Such a quality, that “exists as long as it exists within us”15 speaks of autopoiesis, recursivity, and therefore, complexity. It also speaks of a city that starts with the mind, and acknowledges its strong relationship with the body and the environment, forming an unbreakable structure, that no one discipline can dissolve.

The synthesis of these disciplines creating one universal language could enable a development of the kind which followed the Unified Theory of Physics. This all seems utopia, but I believe a new era is closer than ever. This will be an era where transdisciplinarity will enhance well-being with greater awareness.

This is the era of conscious cities.

References

1 Berg, N. (2016). Can your city change your mind? Retrieved from https://www.curbed.com/2016/11/16/13637148/design-brain-architecture-psychology

2 Varela, F., Thompson, E. and Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. Cambridge: MIT Press.

3 Levine, J. (1983). Materialism and qualia: The explanatory gap. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 64: 354-361.

4 Lewontin, R. (1983). The organism as the subject and object of evolution. Scientia 118:63-82.

5 Varela, F. and Thompson, E. (2003). Neural synchrony and the unity of mind. In Cleeremans, A., The unity of consciousness: Binding, integration and dissociation. New York: Oxford University Press.

6 Clark, A. and Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Retrieved from http://consc.net/papers/extended.html

7 Maturana, M. and Varela, F. (1980). Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, v. 42. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

8 Nicolescu, B., Morin, E., Freitas, L. (November, 1994). The charter of transdisciplinarity. Work presented in the First Congress of Transdisciplinarity. Convent of Arrábida, Portugal.

9 Harvey, D. (1973). Social justice and the city. Oxford: Blackwell

10 Varela, F. (1996). Neurophenomenology: A methodological remedy for the hard problem. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3, No. 4, pp. 330.49

11 The Information Philosopher. Retrieved from http://www.informationphilosopher.com/introduction/information/

12 Jelley, N. (Ed). (1995). The Cambridge companion to Leibniz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

13 Leibniz, G. W. (1989). Philosophical essays. Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company.

14 Bachelard, G. (1994). The poetics of space. Boston: Beacon Press.

15 Alexander, C. (1979). The timeless way of building. New York: Oxford University Press.