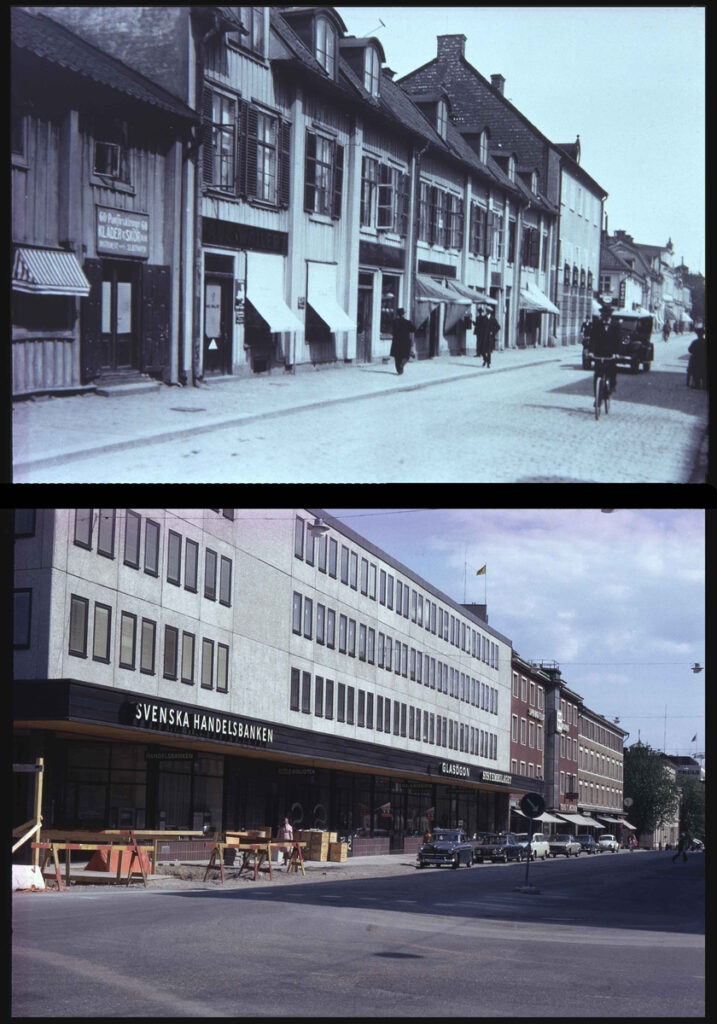

Introduction: historical context

Over the decades, cities have served as the stage for humanity’s story of progress. As societies evolved, so too did their urban landscapes, shaping the ways people live, interact, and thrive. In Sweden, the mid-20th century stands out as a transformative period when sweeping changes were made to urban centres under the banner of modernisation. The 1950s, 60s, and 70s saw ambitious plans aimed at addressing housing shortages and urban decay. These efforts, inspired by modernist ideals, led to the demolition of historic city centres and the rise of functionalist architecture.

While these changes sought to create efficient, clean, and structured urban environments, they left unintended consequences—fractured communities, diminished cultural heritage, and lifeless urban spaces. Reflecting on this period offers an opportunity to examine the impact of such transformations and to gain insights that can inform the future of urban design. Today, as cities grapple with new challenges like climate change, mental health crises, and evolving lifestyles, Sweden’s experience offers valuable lessons on balancing progress with preservation, and efficiency with efficacy.

In this article, we gather knowledge from literature and from interviews with experts in human-centred city planning: Apostolis Papakostas and Jonas Lindström, both professors in sociology, experts in urban sociology and planning at Södertörn University in Stockholm, as well as Alan Dilani, founder of the International Academy for Design and Health, who developed the Salutogenic Design approach at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

Part 1. The drive for utility—and its consequences

The modernisation of Swedish cities during the mid-20th century was driven by necessity. After World War II, Sweden faced a housing crisis worsened by rapid urbanisation. Influenced by urban planning trends from the United Kingdom and the United States, Swedish planners sought to rebuild cities based on principles of functionality, efficiency, and rationality. Modernist architects envisioned cities as machines for living—organised, predictable, and equipped to meet the demands of industrialised societies.

Cities were reimagined as systems to be optimised. In practice, this meant:

- Emphasis on infrastructure over social interaction and community needs,

- Demolishing historic districts in favour of large housing estates and wide roads,

- Functional zoning, where residential, commercial, and industrial areas were physically separated,

Factors behind the decline in social wellbeing

Our conversations with Jonas Lindström and Apostolis Papakostas revealed several interrelated forces which undermined social cohesion:

- Compulsory displacement: Entire communities were uprooted from central districts, fracturing long-standing social networks and community identity.

- Temporary perception: New residential areas were often viewed as transitional. Rising wealth led many middle-class families to move again, creating instability and limiting investment in local relationships.

- Fragmentation and isolation: Functional zoning separated homes from services and workplaces, reducing spontaneous daily interactions and weakening community life.

- Loss of social cohesion: Residents were often relocated to unfamiliar areas where they had no existing social ties, leading to a loss of community support, trust, and a sense of belonging.

- Lack of identity and continuity: The sudden change in environment disrupted the continuity of daily life, affecting personal identity and cultural connection. Familiar routines and community landmarks that provided a sense of stability were lost.

- Aesthetic uniformity: Functionalist architecture, while innovative in purpose, often resulted in monotonous environments. Residents found themselves living in buildings that lacked warmth and individuality, leading to a sense of alienation. Eye-tracking studies and psychological research (Rosas et al., 2023) show that architecture with low sensory variation can hinder perception, navigation, and emotional engagement with place.

These combined factors contributed to negative psychological outcomes such as stress, anxiety, and depression.

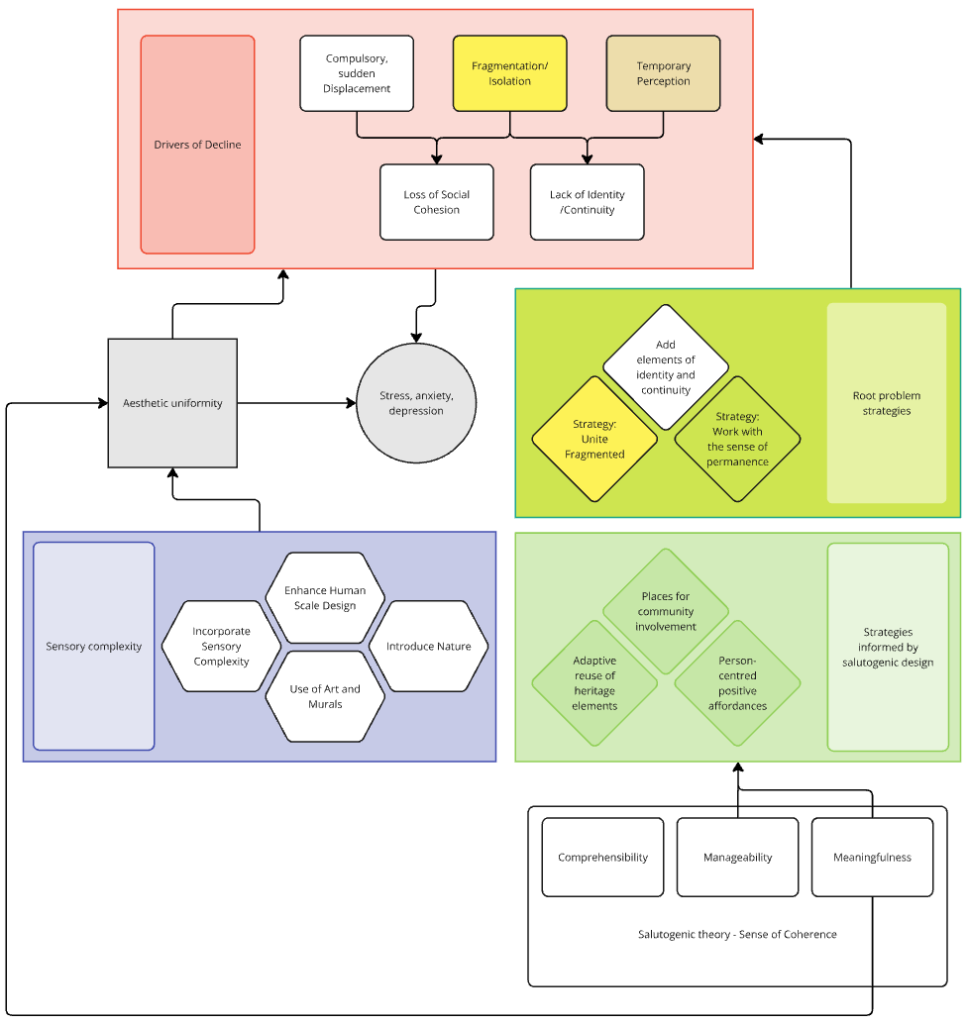

Mapping the problem: what remains?

Although large-scale urban displacement is less common today, its effects persist. Many mid-20th-century city centres remain functionally and socially fragmented. Their architecture is often perceived as cold, repetitive, and lacking in human scale. Residents struggle to form emotional attachments to such environments, which lack a strong sense of identity, continuity, or permanence.

The question “Should we demolish city centres and build in different styles?” has resurfaced in Sweden—this time referring to the very modernist developments built during the post-war era. However, given the past experience with disruption, it appears that preserving and transforming these areas has advantages over demolishing them once more. A new wave of demolition risks repeating historical mistakes—disrupting continuity and further eroding trust and cohesion.

Instead, transformation should be adaptive:

- Uniting fragmented spaces;

- Working with permanence, creating environments that feel lasting and stable;

- Reintroducing identity and continuity into the everyday urban fabric.

Part 2. Salutogenic Design: a framework for urban well-being

Developed by Aaron Antonovsky, the salutogenic model of health (Mittelmark et al., 2017) focuses on promoting health and well-being rather than merely preventing illness. Alan Dilani, who pioneered its architectural application, emphasises the concept of a “sense of coherence”, which supports human resilience and happiness. This sense is built on three core elements:

- Comprehensibility: People understand and can predict the environment.

- Manageability: People feel equipped to deal with their environment.

- Meaningfulness: People see purpose and value in their surroundings.

Architect Jan Golembiewski has worked to translate these pillars into practical strategies for urban and architectural design:

Comprehensibility:

Designs should create clear, legible spaces. For instance:

- Intuitive layouts and signage

- Welcoming transitions between spaces

- Landmarks for orientation

- Predictable structures that improve wayfinding

Example: A square with a focal point and visible paths to surrounding amenities allows people to form mental maps and navigate confidently.

Manageability:

Environments should offer users the tools and infrastructure to engage effectively:

- Accessibility for all abilities

- Safe and well-lit public areas

- Supportive amenities (e.g. shade, toilets, seating)

- Positive affordances—features that suggest and support desired actions

- Stress-reducing and ecologically sustainable design

Example: A subtly sloped kerb invites pedestrian crossing and signals accessibility.

Meaningfulness:

Design should stimulate connection, purpose, and engagement:

- Historical continuity through adaptive reuse;

- Places for co-creation and community participation;

- Cultural expression and symbolism;

- Positive choices that promote well-being.

Example: A refurbished historic building repurposed as a community space maintains cultural memory and invites meaningful use.

According to Dilani, places that lack meaning or sensory engagement risk becoming alienating. Design must evoke positive emotion and identity.

Applying the salutogenic lens

Two of the most harmful consequences of mid-century demolitions were the loss of social cohesion and the erosion of identity and continuity. Using salutogenic design as a planning checklist makes it more likely that such social dimensions are actively considered.

When viewed through this lens, Sweden’s mid-20th-century developments score:

- High on comprehensibility (orderly layouts);

- Moderate on manageability (some accessibility and infrastructure);

- Low on meaningfulness (limited emotional connection and cultural identity).

To strengthen these areas, design strategies might include:

- Opportunities for community involvement;

- Adaptive reuse of existing structures;

- Positive affordances that guide behaviour gently and intuitively;

- Strategies to combat aesthetic uniformity and introduce sensory richness.

Aesthetics are not just a luxury—studies including Yeang and Dilani (2022) confirm their impact on well-being. Rich architectural details, texture, and art provide emotional stimulation and “positive distraction.”

To enhance the sensory and emotional quality of modernist environments:

- Add sensory complexity with varied textures, colours, and materials;

- Design at a human scale to encourage social interaction;

- Introduce nature to soften the built environment and promote calm.

Revisiting history to shape the future

The full map of the problem-solution relationship for the Swedish city-centres could look like this:

Sweden’s experiences during the 20th century serve both as a cautionary tale and a source of inspiration. The demolitions of the 1950s to 1970s remind us of the risks of prioritising efficiency over long-term human and ecological impact. However, they also highlight the potential of urban planning to drive positive change when informed by a deeper understanding of human needs.

As cities adapt to new realities—such as remote work, e-commerce, and demographic shifts—they must balance between preserving heritage and introducing innovation. Adaptive reuse, which repurposes old buildings and incorporates meaningful sustainable solutions, while maintaining their historical character, offers a promising path forward.

Part 3. Case study of a healthy city district: Alecta Fastigheter och Nordr in Värtahamnen

In 2022, Swedish real estate developers Nordr and Alecta Fastigheter, together with RISE – Research Institutes of Sweden – were appointed by the City of Stockholm as anchor developers for the new district of Valparaíso in northeastern Stockholm. The area, a former port district, is located close to the city centre but presents challenging conditions due to surrounding traffic, both on land and water.

The approach taken by the developers was to base the planning process on research and evidence, guided by the central question: Can we build a city that promotes happiness and well-being for its residents?

In parallel with the planning process, Alecta, Nordr, and RISE, in collaboration with interdisciplinary experts, deepened their knowledge and expanded the urban planning toolbox, aiming to challenge conventional norms and integrate salutogenic design from an early stage. During 2023, a series of think tanks were organised in collaboration with experts in fields ranging from neuroarchitecture and happiness research to ethnology and economics. Based on insights from these think tanks, supplemented by an in-depth literature review, Alecta, Nordr, and RISE identified five key focus areas for the development of the new district of Valparaíso. These thematic areas were defined based on available research, identifying the strongest evidence-backed connections between the design of the physical environment and human health and well-being.

1. Building with and for nature

The integration of green spaces, biodiversity, and natural elements in the city is one of the most well-supported and extensively studied interventions to enhance well-being in urban environments. Research indicates that access to green environments reduces stress, improves mental health, and fosters social interactions (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989). Introducing nature into environments characterised by aesthetic uniformity brings sensory complexity. Incorporating vegetation into public spaces, rooftops, and façades enhances sensory experiences and strengthens the sense of place and belonging.

2. Planning for movement

Walkable and well-connected cities support both physical health and social well-being. Studies highlight that pedestrian-friendly environments encourage active lifestyles, reduce air pollution, and promote spontaneous social interactions (Kommittén för främjande av ökad fysisk aktivitet, 2023). By designing cities from a pedestrian’s perspective, we can strengthen urban spaces with sensory enrichment, allowing details to be discovered at a human pace. This also brings greater proximity between key destinations, making urban spaces more accessible and interconnected, reducing reliance on cars, and fostering community ties—ultimately uniting what has been fragmented.

3. Designing for the five senses

The built environment influences how people perceive and interact with their surroundings. Research shows that environments with varied materials, textures, and interactive elements stimulate cognitive function and emotional well-being (Roe & McCay, 2021). This supports the strategy of working with sensory complexity, ensuring that architecture and urban design engage multiple senses, making public spaces more inviting and meaningful.

4. Fostering community

Social cohesion and a sense of belonging are vital for the well-being of both society and the individual. Well-designed communal spaces that encourage interaction can strengthen social networks, reduce feelings of loneliness, and help unite fragmented areas. Accessible gathering spaces are crucial in fostering relationships and community engagement.

5. Shape environments for safety and trust

Safety and trust are fundamental to people’s well-being, building resilience and robustness within society. Research suggests that well-lit streets, active ground floors, and transparent architectural designs enhance the perception of safety and foster social trust (Ceccato et al. 2019). This principle aligns with the strategy of working with the sense of permanence, where stable and well-maintained environments promote long-term attachment to a place and contribute to overall mental well-being.

In the planning process for Valparaíso, it became clear that conventional urban development processes do not prioritise long-term issues related to human health and well-being, focusing primarily on project economics. Although there are well-documented correlations and long-term cost savings at a societal level, these factors are often excluded from project-specific economic calculations, which mainly consider potential saleable area and the fulfilment of functional requirements. This highlights the need for a more holistic economic perspective in urban planning, as well as policies and regulations that integrate well-being and sustainability into decision-making, rather than treating them as secondary concerns.

The role of policy and global movements

Urban transformation does not occur in isolation; it is shaped by policy frameworks, global initiatives, building techniques, economic factors, and societal values. It is also a delicate balance of multiple factors, all of which must coexist within a shared space to create the cohesive structure we call a city. Creating a vibrant, human-scaled environment that enhances the well-being of its inhabitants requires a combination of knowledge, political commitment, and economic incentives.

Sweden’s “Policy for Designed Living Environments” and the European Union’s New European Bauhaus initiative are two modern efforts to reorient urban development toward sustainability, inclusivity, and aesthetic enrichment. These policies provide a foundation for addressing the structural and social issues that partly emerged from modernist urban planning while setting a course for more human-centred cities.

Conclusion: Toward human-centered, resilient cities of the future

The cities of the future will be judged not only by their infrastructure but by their ability to nurture human connection, resilience, and well-being. By embracing salutogenic design, participatory planning, and sustainability, urban planners can create spaces that meet the diverse needs of modern society.

Sweden’s evolving urban landscape serves as a reminder that progress is most meaningful when rooted in understanding of people and communities. As we reimagine our cities, the goal must be not just to build structures but to shape communities that thrive in harmony with each other and their environment. By learning from the past and innovating for the future, we can create urban spaces that truly embody the essence of human-centred design.

This vision is exemplified by the work of Nordr, Alecta Fastigheter, RISE, architects like Alan Dilani, and experts like Jonas Lindström, Apostolis Papakostas, who continue to push the boundaries of what urban spaces can achieve.

Emphasis should also be placed on integrating the built environment into a broader public health policy framework. Health and well-being policies including urban space and architecture could help developers and architects commit to common social goals and provide them with the effective guidelines.

References

Alfvén, G. (2016). Ohälsosam Arkitektur: En annan sida av funktionalismen. Stockholm: Balkong Förlag.

Ceccato, V., Vasquez, L., Langefors, L., Canabarro, A., Petersson, R. (2019). En trygg stadsmiljö: Teori och praktik för brottsförebyggande & trygghetsskapande åtgärder. Stockholm: Institutionen för samhällsplanering och miljö, Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan. ISBN: 978-91-7873-321-7.

Dilani, A. (2005). Psychosocially supportive design. Design and Health IV: Future Trends in Healthcare Design; Dilani, A., Ed, 13–22.

Dilani, A. (2008). Psychosocially supportive design: A salutogenic approach to the design of the physical environment. Design and Health Scientific Review, 1(2), 47–55.

Golembiewski, J. A. (2022). “Salutogenic Architecture” in The handbook of Salutogenesis. eds. M. B. Mittelmarket al., 259–274. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-79515-3_26

Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S (1989), The Experience of Nature: A Psychologic Perspective, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kommittén för främjande av ökad fysisk aktivitet (2023) SOU 2023:29 Varje rörelse räknas – hur skapar vi ett samhälle som främjar fysisk aktivitet? Available at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/b4d008ff11b349e-8992aef9e95bc19c2/varje-rorelse-raknas.pdf

Mittelmark, M. B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G. F., Pelikan, J. M., Lindström, B., & Espnes, G. A. (Eds.). (2017). The Handbook of Salutogenesis. Springer.

Roe, J., McCay,L. (2021) Restorative cities, Urban design for mental health and wellbeing, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Rosas, H. J., Sussman, A., Sekely, A. C., & Lavdas, A. A. (2023). Using Eye Tracking to Reveal Responses to the Built Environment and Its Constituents. Applied Sciences, 13(21), 12071.

Yeang, K., & Dilani, A. (2022). Ecological and Salutogenic Design for a Sustainable Healthy Global Society. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.