Work plays an influential role on our lives, and the quality of working environments can have considerable impact on our health and wellbeing. In the UK there are 20 million workers who work in office-based organisations1, and who will spend an average of 37 hours a week in these environments. In recent years there has been renewed focus on workplace design and its impact on workers’ productivity and satisfaction, particularly in open plan offices. Extensive research has been conducted to date on the topic of Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ)2. It is estimated that the UK loses 570,000 hours per year due to workplace absences linked to poor building design3. Understanding the impact of our offices on the people who use them has the potential to improve wellbeing for millions of people, and to improve productivity for organisations. However, the social and cognitive psychological mechanisms related to IEQ have not yet been thoroughly investigated.

The impact of workplace design includes both our physical responses to the Internal Environmental Quality, and our psychological responses to these spaces. Understanding the connection between the built environment and how our brains process the information we gather from the world around us is an important aspect of designing a successful workplace, and understanding how spatial and social features of the work environment can be optimized to improve wellbeing and productivity is a key part of this.

Workplace design has entered a new paradigm where ‘agile’ and ‘flexible’ working are commonplace terminology and organisations now have to consider where people work as a significant factor in the competition for new talent. These more mobile workstyles have emerged that allow workers to choose how and where they work, from different areas within a building, different types of environment, and even to different locations across an area, city or even globally4, supported by rapidly evolving technology.

These emerging working styles also reflect trends to improve utilisation of offices, and to maximise the value of the floor space available. Flexible working styles have also been driven by the rise of ‘knowledge workers’, who have more varied work tasks and activities that they may undertake in a typical day or week. A recent report from the British Council of Offices identifies these changes to working practices and the increasing fluidity of office structures as one of the most influential trends in office design currently, based on a comparison with a previous study published by the BCO in 20135.

The meaning and definition of these terms tend to change across organisations and companies, and can encompass anything from hot-desking, home working, to a variety of space or co-working, where organisations choose a location in a shared office environment. Offices such as Facebook (Menlo Park, Frank Gehry), and Sky Central (West London, PLP Architecture) have moved towards very large open plan offices, but also include a wider range of workspaces and meeting areas to support the increasing variety of activities taking place across their workforce. Co-working spaces, such as WeWork, are becoming increasingly popular as they allow short term leasing of space by desks, while also providing a wide range of shared amenities for occupants.

Another variation of flexible working is Activity Based Working (ABW) which aims to provide a variety of different work settings within an office that can support different tasks. Occupants are then able to choose the setting that best suits the task they are performing, and the type of space that they prefer. While flexible or agile workplaces are often designed to be as minimal and standardised as possible, to accommodate fluctuations in a workforce, the emergence of ABW is in part an attempt to provide a more personalised version of flexible working. It aims to provide greater control, ownership and comfort within flexible or agile workplaces and to promote staff collaboration and productivity6. In addition, ABW style offices can allow for the specific tailoring of a workplace design solution that accommodates different building user group profiles, based on common preferences and personality traits, which in turn influence our perception of the environment.

Do we know the success factors and how to measure them?

With the potential of ABW style workplaces established, we now need to ask ourselves ‘do we know enough about the different success factors of a workplace design to tailor the design of ABW environments? And do we know enough about the extent to which personal preferences or personality influence the success of a workplace?’

To better understand the success factors of office environments and which specific spatial attributes may impact how people respond to the physical space they inhabit, we brought together a group of psychologists, social scientists and designers to develop and share research across disciplines, and examine psychological responses to workplace design7. Our objective was to understand how spatial and social features of the work environment can be optimized with methods and techniques developed for exploring cognitive and psychological responses, to provide new insights into the complex relationships of different spatial attributes of the workplace. A series of five studies were undertaken considering spatial and social cues on perspective taking, and specific attributes of social and spatial density, differing visual contexts or views, and sound level.

The first three studies used survey-based visual perspective taking tasks (VSPT) using Lego figures (agents) and objects (non-agents), to investigate spatial cues and to determine how people mentally represent the world in spatial and social terms. VSPT is an individual’s ability to imagine the relative locations of others, objects or environments from a viewpoint different than his/her own. Eye tracking was included within one of the VSPT tests to better gauge how we spatially read our environments.

The final two studies considered how these spatial and social cues might occur in a specific environment, namely an office, and how they might then interact with other spatial and environmental variables. Virtual reality (VR) environments were used to study these variables, and participants also completed visual perspective taking tasks and surveys. The use of VR provided us with an opportunity to examine multiple variables in a controlled setting, which is not possible in a live environment. As VR becomes more prevalent within the built environment sector to engage with and explore designs, this study also provided an opportunity to explore the validity of VR environments as a proxy for human response.8

Key findings

Stimuli & distractions in the workplace

Open plan office environments are the subject of an ongoing debate and present a dichotomy of positive and negative responses9. They are often described as confusing and non-productive, but also beneficial to collaboration and in some instances improved productivity, providing both distractions and stimuli.

Using multiple modality virtual reality environments (visual and auditory) allowed us to test these interdependent variables of the physical space. As expected, the studies found that noise level has a negative impact on perceived work quality and increase feelings of distractions. It was also found that ‘view’ or different visual contexts can influence our experience in the workplace, and can be compared in terms of distraction and level of stimulation.

It has been shown in previous studies that having access and views of nature has proved to have positive effects on health & wellbeing, such as lower stress levels. Providing access to a view of green external areas, a green roof for example, for as short as 40 seconds has also been shown to increase concentration levels.10 Our results supported this, with offices that have a view to an external scene were found to positively affect participants, leading to an increase in perceived work quality and less perceived distractions.

However, we also found less obvious impacts of views, as people also felt more ‘crowded’ in offices with an internal view, rather than an external view. This indicates that providing external views could help to mitigate the negative impact of offices where density is particularly high. It could also support space planning, when considering where to locate areas for focussed work.

Overall, we found that while different types of view will alter perception of a workspace, these differing visual contexts have much less influence on work quality or distraction than sound level. Understanding the hierarchy of different types of auditory and visual stimuli allows designers to prioritise investment in design, and to consider mitigation measures through design, depending on the project constraints. Future studies will consider more variations of the type of distractions in a workplace.

Spatial & social densities

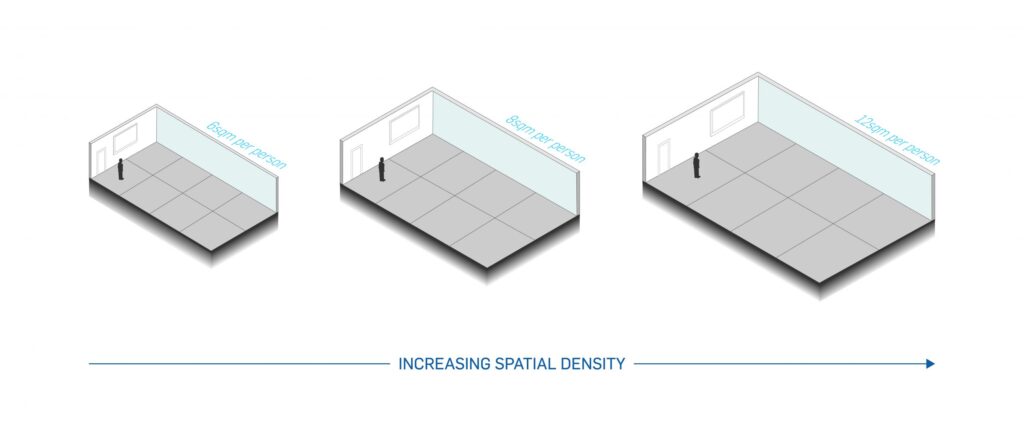

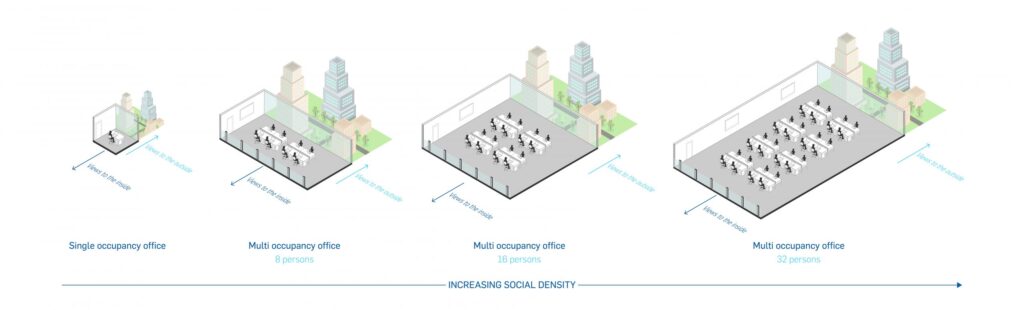

The amount of space provided per person in the workplace is known as spatial density, and the number of people in an office is known as social density. The amount of space or spatial density in an office can have a significant impact on our wellbeing, too little and we feel crowded, stressed or uncomfortable11. Too much space or too great a distance between colleagues and we feel disconnected to others12,13.

A recent study considered the relationship between reported workplace satisfaction and Internal Environmental Quality (IEQ) factors14, and found that satisfaction with the ‘amount of space’ a respondent had was the best predictor of overall satisfaction with the building they worked in.

We found that spatial density has a more significant influence on our perception of personal space and cognitive ability in the workplace, than social density. As expected, we found that increasing the amount of space improved both results. However, we found that increasing spatial density eventually levelled off, providing a threshold of a workplace density of approx. 8sqm per person, above which additional space was found to have very little positive effect.

The perception of personal space and crowding was also studied across different social densities, to test how the number of people in a space makes us feel. Being in a single occupancy room made people feel they had more space than when they were sharing with others, but when we considered multiple-occupancy offices, the actual number of people in the space (social density) was not found to have a significant impact on perceived personal space, feeling of crowdedness or perceived work quality, until the number of people reached thirty-two, when it had a small but significant negative effect. This may indicate that increasing the number of people in a shared office above thirty-two will start to see work quality decrease and distractions increase, something that we hope to consider in future studies.

Overall, we found that the amount of space per person has a greater influence on us than the number of people in an open plan office, but that there are also thresholds for both spatial and social density, which could be used to define the spatial layout of work areas or neighbourhoods in an office. The extent to which different types of activities might be more or less suited to larger or smaller shared workplaces should also be considered and is another area that would be valuable for future studies.

Control & variety of space

Control of environments has also been shown to influence satisfaction and wellbeing in a workplace15. Control can refer to environmental conditions, your ability to adapt your workplace or being able to choose between a variety of spaces to work. This relates to our feeling of ownership within a space, with greater control contributing to greater feeling of ownership and responsibility over a working environment.

Part of the study considered the difference between single occupancy and multi-occupancy work areas. Participants responded differently in these different spaces, with some spaces considered conducive to work quality, and others to social aspects.

As might be expected, work quality was perceived to be highest in a room without any other people, and work quality in a single occupancy workplace improved again when participants were provided with a view to the outside. This type of space would support concentrated or focused work within an activity based working environment. It highlights the importance of providing some areas within a workplace where people can work alone when needed, but also that this type of environment should provide views if possible to aid concentration restoration16. Although we are unlikely to see a resurgence of cellular office layouts we need to consider the provision of dedicated quiet working areas, potentially for single occupancy. This will also be dependent on the type of work and tasks being undertaken by an organisation.

Providing a variety of different space types, from shared workstations to single occupancy spaces for focussed working, is particularly important in activity based workplaces, or for offices which are highly collaborative in nature (e.g. design, communications, etc) which can provide a more interactive workplace with opportunity for control and choice.

Personality type

As designers we are aware that ‘one size does not fit all’, and the key to providing workspaces that support the wellbeing of occupants is understanding the traits and preferences of different user groups in a certain building. These differences can depend on the activity, the way a person prefers to work, and their personality.

There are many ways of defining and assessing personality, but one of the most commonly used in the UK, and particularly in the workplace, is the five-factor model (FFM) or the ‘Big 5’, which defines five key factors of personality; Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism17.

We found that people who rated highly on different aspects of the personality model, had some differences in their responses to each study, which may explain why some people thrive in open or agile workspace, and others are more easily distracted in shared offices.

These traits are not as simple as extraversion and introversion, but cover a wide range of cognitive tendencies which may influence eye movement towards activity, or increased awareness of personal space. For example, some of the results we found suggest that those who score highly on ‘agreeableness’ and ‘extraversion’ were found to be more susceptible to visual distractions, and those who scored highly on ‘extraversion’ and ‘conscientiousness’ were more aware of personal space and boundaries than others.

Conclusion

Given the number of office workers in the UK and the consequences of poor workplaces, understanding how different aspects of offices impact our wellbeing, has the potential to unlock numerous benefits for businesses and individuals. The studies will enable us to better define thresholds for distractions, spatial and social density, considered against the activities, tasks and personality profiles of different groups within a workforce and building.

Greater insights into the relative impact of environmental and spatial variables can also help to better define a client’s brief, based on the priorities for that project, and taking into account financial, spatial or contextual constraints. This can then support spatial planning and design to provide the right amount of space for the different groups of people, tailoring the spatial layout and ratio of spaces to suit the specifics of a user group.

As activity-based working becomes more prevalent, a ‘one size fits all’ approach to design can no longer be considered. This style of working requires a better understanding of the attributes that support different activities, work tasks, or people.

We need to understand the specific requirements of different user group, taking into account the role that personality type and preference play, by actively engaging with building users in the design process. Understanding the broad profile of different user groups within an office or building will ensure that the design includes the correct mix of different spaces and spatial attributes which are most suitable to support those groups. Moreover, understanding our psychological responses to a workplace is as important as our physical responses to ensure the workplaces of the future are productive and healthy.

References

1 Atkins Research (2016). Draws upon ONS Business Estimates, Regional GVA Estimates, Health & Safety Executive and Land Registry data – All 2015. Supported by CABE (2006). The Impact of Office Design on Business Performance. British Council for Offices amongst others. http://atkins-hcd.com/the-economic-benefits-of-hcd

2 Y Al Horra et al (2016). Occupant productivity and office indoor environment quality: A review of the literature. Building and Environment. 105:369-389

3 J.Guest (2016). The economics of human-centred design study. Atkins research. http://atkins-hcd.com

4 Research undertaken by Atkins and Burges Salmon (2018). Future Transport: The implications for office demand and design. British Council of Offices. http://www.bco.org.uk/Research/Publications/Future_Transport_The_implications_for_office_demand_and_design.aspx

5 Research undertaken by Ramidus and AECOM (2018) Office Occupancy: Density and Utilisation. British Council of Offices. http://www.bco.org.uk/Research/Publications/Office_Occupancy_Density_and_Utilisation.aspx

6 Leesman (2017). The rise and rise of Activity Based Working. Leesman index. http://www.leesmanindex.com/research/

7 Proulx, M. J., Todorov, O., Taylor Aiken, A., & de Sousa, A. A. (2016). Where am I? Who am I? The relation between spatial and social cognition in the built environment. Frontiers in Psychology

8 Esenkaya, T., Jicol, C., Brown, D., O’Neill, E., Proulx, M., & de Sousa, A. A. (2017). A LEGO study: Influence of spatial and social cues on perspective taking. Poster presented at Urban Wayfinding and the Brain, London, UK.

9 A. Shafaghat, A. Keyvanfar, H. Lamit, S.A. Mousavi, M.Z.A. Majid (2014). Open Plan Office Design Features Affecting Staff’s Health and Well-being Status. Jurnal Teknologi, 70 (7)

10 K.E Lee et al (2015). 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42:182-189

11 E.T Hall, (1966) The Hidden Dimension. New York: Doubleday

12 T J. Allen, G. Henn (2006). The Organization and Architecture of Innovation: Managing the Flow of Technology. Elsevier, New York

13 T J. Allen (1984). Managing the Flow of Technology: Technology Transfer and the Dissemination of Technological Information Within the R&D Organization. MIT Press Books

14 J. Kim, R de Dear (2013) Workspace satisfaction: The privacy-communication trade-off in open plan offices. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 36:18-26

15 J. Kim, R. DeDear, et al (2016). Desk ownership in the workplace: The effect of non-territorial working on employee workplace satisfaction, perceived productivity and health. Building and Environment. 103:203-214

16 K.E Lee et al (2015). 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42:182-189

17 J M Digman (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology. 41:417-40