Participating Artists:

Eleonora Cattaneo, Matteo Esposito, Giorgia Mazzaferro, and with the collaboration of Stefano Fardelli and Susanna Beltrami.

In a society where the cult of the image becomes increasingly pressing, spaces are frequently designed to please the gaze. Architecture is often described as a combination of beauty and function but beauty is not only related to what we see; it’s a pleasure related to all the senses (Pallasmaa, 2012). Architecture is the stage on which we perform our lives every day. Hewitt in “Social choreography” (2005) tries to think of he aesthetic as it operates at the very base of social experience. He looks at choreography as the disposition of bodies in space, and examines a more lateral transcendence. This research project explored the possibility that depriving the body of relying on one of its fundamental senses (sight) does not result in a less profound performance, but instead, the other senses compensate sate generating a different exploration of space; the performance was conducted by contemporary dancers.

A performance conducted by professional dancers does not aim to be “purely science,” but instead to tell about exploratory behaviour without sight: dancers have a deep focus on the performance.

Space Exploration: Theoretical Contexts

Vision offers distinctive and unique pieces of information (e.g., colours, perspective, shadows, etc.). It’s also true that sight-gifted people always construct reality at the neural level, shaping images (University of Bath, 2013). Research indicates that combining visual and auditory cues improves memory-guided spatial navigation, highlighting the role of multisensory input in spatial tasks” (Nature, 2023). Furthermore, the integration of visual and self-motion cues enhances navigation abilities, suggesting that both visual and self-motion information are crucial for effective spatial navigation” (PubMed, 2022). Experiments using immersive virtual reality have demonstrated that audio-visual navigational aids can counteract the limitations of visual-only or auditory-only GPS systems, emphasising the benefit of multi-sensory cues in spatial representation (Nature, 2022). Several observations indicate that vision might not be so necessary to form a proficient mental representation of the world around us. Indeed, individuals who are visually deprived since birth show perceptual, cognitive, and social skills comparable to those found in sighted individuals (Ricciardi et al., 2006, 2009, 2014, a,b). Touch is related to sight: while exploring through touch, the brain elaborates an image, which might only belong to the semantics of the object, not corresponding to the real one. A specific topic now emerging in the neuro-architectural debate deals with the relationship between sensory experience and architectural perception. The role of non-visual perceptual modalities, and specifically of touch, is currently arousing great interest (e.g., Pallasmaa, 2012).

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study demonstrated that the brain integrates visual and tactile information, influencing spatial perception and object interaction. The findings revealed that certain brain areas exhibit greater activity during combined visual and tactile (visuo-tactile) conditions compared to when each sense is engaged separately (Grefkes & Fink, 2011). Through touch, the brain captures and stores physical sensations which are then brought back to the mind with images connected to them or even just with the imagination and vice versa, starting from visual images, the brain associates sensations, animals use sounds to compute an object’s location in space, similar op erations happen in the auditory system of humans. (Pillai,1995). The sight is a very social sense; interactions of any kind are often influenced by what we see. In the dark, we have a better understanding of our body, This happens because we are not distracted by what we see; we focus more on other stimuli, often ignored because overwhelmed by the gaze. This leads to some crucial questions: how would space exploration change if the main impulse stops being an image and becomes the sound, the feeling of the presence of other people, the impression of a space furnished with objects belonging to a different use? How do the relations with those objects or other people change? Does the space get a different “beauty”? Is there a way to design a space that allows a more instinctive exploration?

Dance Practice Context

Dance is an art that implies spatial performance, and is often accompanied by music; space exploration is at the base of this art. Pina Bausch, in the seventies and for the first time, brought to the scene the real experience of the dancers. Those years saw a radical change in terms of body expression. The relationship with space and music found a new way of being on stage thanks to a freer exploration of movement and new gestural codes. In Cafe Muller (Image 2), dancers stumble among everyday objects (tables and chairs), and most of them perform this piece with their eyes closed. Improvisation is leading the scene, and the personal experience of every performer creates a unique entanglement; the show is never the same. Performance is a need more than a choreography.

Bausch stated: “It is almost unimportant whether a work finds an understanding audience. One has to do it because one believes that it is the right thing to do. We are not only here to please, we cannot help challenging the spectator” (Wenders, 2012). In the “UNSEEN” (Image 3), Stefano Fardelli let the dancers work blindfolded; his movements were limited. This deliberate constriction gave birth to a unique quality of movement, inspired by the experience of local people in those days. Then the dancer was asked to learn the most interesting movement sequences by studying the material filmed during rehearsals. The result is a piece where the dancer is not blindfolded, but can achieve the same quality of movement that has been created in the dark, with all the limits, the hesitations, and the outbursts of those who seek the light.

THE EXPERIMENT

This research compared differences in terms of space exploration, socialisation, trajectories chosen, and consequent emotions, while repeating a performance with all the same arrangements except one: the chance to see. The space was equipped with daily use objects, positioned both on the borders of the performing space and some in the middle of it. Dancers were dressed up in black, tight-fitting clothes, and the space was white (to ease the mapping). They reached the space accompanied so they could be blindfolded. In the blindfolded performance, they followed the music and their balance relied mostly on their ears. Physical exploration, on the other hand, can rely only on touch and smell. Four cameras film the scene from the corners of the room to record movement patterns, the number, the duration, and the typology of interactions. Smart watches detect the heartbeat.

Observation before the performances

To better design the staging for the performances, a first observation took place during an ordinary dance training in the academy. The dancers were asked to practice fluidity while awakening their bodies and exploiting the different forces applied to them by the spatial dimensions. This exercise was conducted with the eyes closed. The result helped shape the performance.

1st observation: Solo Performance

During this phase, the dancers experimented with the space alone, becoming aware of their bodies, exploiting the forces applied to them by the different spatial dimensions (Image 4). The main aspect observed in the first performance was the strong power exercised by the ground: a union of forces that pushed the dancer up and then pull them down, “every frontier is simultaneously a bridge: every flowing into is also a way of hardening edges, articulating a boundary….Why not appropriate this double stance of any “contact”—establishing both a frontier and a bridge—for conceptualising the already “never fixed/ in-flux” bodies? Weren’t they constantly trying to differentiate themselves from others while dying to loosen those boundaries to flow?” (Potuoglu 1996).

When the dancers finally stood, the connection to the ground was still strong, but another dimension was applying its strength. Possibilities increased, and exploration became wider. In this phase, the ground was still playing its role, but the verticality offered new chances that the dancer explored widely. Touch acquired a new importance: it’s the best tool to explore and understand the limits of the spatial invasion. The walls acted like opponents, generating the contrast at the base of the movements.

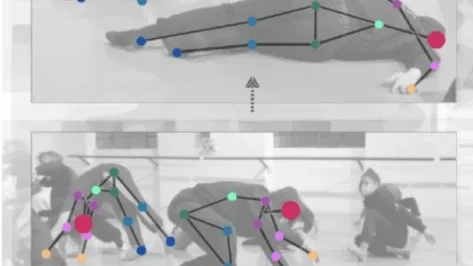

2nd observation: Spontaneous Groups

In the second phase (Image 5, 6, 7), dancers open up to a deeper exploration, the social one. They met other bodies and exploited the possibilities offered by these while adding a fourth spatial dimension: others. Every small space they found was a good access to slip on and get closer, tighter to each other. The result was a harmonious entanglement of bodies that seemed guided by one soul. They kept their eyes closed, trying to get the best out of each other. The performance was fluid, unique, and the objective was accomplished.

3rd observation: Appointed Dancers

In a third phase, dancers participating in the project were asked to dance together (Images 8, 9, 10). The result was a rigid, unnatural, and at times jarring performance. They were dancing together for the first time, and they were aware that they were being observed as part of a project. They didn’t slip on empty spots, they tried to compose, to build a choreography, to please the gaze. The result wasn’t harmonious; instead, it looked like an exercise that had not succeeded. The performance was jarring and unpleasant. The impression was that of a strong effort in contrast with the idea of fluidity.

Findings After the First Observation

As a conclusion of the first part of the project, it can be said that fluidity is possible only when the consequences of a choice are considered. There is indeed a notable difference between the social dancing conducted with chosen co-dancers and the one conducted with the appointed colleagues.

The main method was visual ethnography, the observation of patterns of movement and analysis of the dancer’s pace. Cameras were positioned in all the corners of the room and recorded both performances. Dancers wore wristbands that detected their heartbeat. Individuals’ engagement with their environment and adaptation to changes is a crucial focus in evolutionary biology. Among the physiological measures that offer a quick indicator of autonomic nervous system activation and that can be easily assessed, there is the modulation of heart rate (Wascher, 2021). After the performances, we interviewed the dancers and asked for their impressions and feelings about the performance. A triangulation of these data provides an overview of the emotions experienced during the two performances, physiological responses might help to confirm them.

The impossibility of predicting and visualizing what the space looks like is expected to be the biggest emotional trigger during the first performance. Emotions are, neurologically speaking, a prediction themselves, according to Lisa Feldman Barrett (Feldman Barrett 2015). Predictions are the way our brain works. They are at the base of every action we take, predictions are what allow us to understand the words we are listening to or reading. They help us to make sense of the world. We don’t react to the world, but based on our experience, we predict and construct our experience of the world. Trying to understand emotions, we also make predictions of what it could (or should) be according to our experience. The emotions we seem to detect in people come from what we think in our minds. The way we experience our own emotions is the same: our brain makes predictions or guesses that are constructed in the moment by millions of neurons working together. Architecture and the built environment might work together or against predictions, contributing or working in contraposition to the internal or external balance at the base of our emotions through space coding and the construction of reality. Designing is somehow predicting a prediction, working together with emotions, and the way they are intrinsically entangled with space.

Measuring emotions is an activity still under discussion, according to Sarah Mae Sincero “most researchers measure emotions of people based on their affective display, that is, their emotional expressions. Affective display includes facial expressions, bodily postures, and vocal expressions. To measure affective display, researchers generally use observation techniques and self-report via questionnaires. At present, they also utilise computer programs that can code expressive behaviour and read the emotion of an individual.” (Sarah Mae Sincero, 2012).

In light of this, we can assume that if we deprive dancers of the opportunity to make predictions, they might exhibit a behavioural response that does not comply with the “expected” one. This effect may be amplified by the presence of objects that alter the semantic context. In a study about space ecploration and the implication of semantic on users perception and behavior, researchers affirmed that “space offers the possibility of attribution of a different semantic from the conventional ones (attributed according to experience), and this margin of creative freedom satisfies the need to carry out the activity and from this may derive a certain degree of satisfaction and temporary or stable gratification for the individual” (Brancaccio et al 2020).

The research aimed to understand how bodies and space relate to each other and how bodies cooperate in a space if relying on other senses rather than sight. Furthermore, it aims to investigate the different emotions experienced during performances characterised by both the presence and the absence of sight in space performing and the potential tools involved in this mechanism. It expects to find a sort of reduction of the instinctive response to space and other people, and a deviation in spatial performance.

Blind vs. Open Eye Performance

- Predictions: How does the absence of fulfilled predictions influence the behaviour of dancers?

- Spontaneity ve intentionality: Can the blind folded exploration relieve some of the feelings generated by a performance where intentionality overcomes spontaneity? How do dancers feel about safety, unexpected elements, and privacy in both performances?

- Differences in borders’ perception: Do borders help to build the space map when blindfolded or become elements of friction/interaction? Do dancers move/work with them?

- Differences in human interaction: How does the cooperation between dancers work when they can and can not see each other?

- Visual images: what are the differences and the analogies between the brain images produced during the performances?

Music, together with the instinct of exploration, guides the movements, obstructed and encouraged in the same time by the privation of sight. Elements “not belonging” are also a challenge: the question “Why here” brings to another one, “how could I use it?

Blindfolded Performances

The music started, and nobody moved. It seemed they were looking for a “vision” to come up. Slowly, two of them started touching and measuring the borders of the objects, holding and surrounding them. One was still. Gravity in the beginning is the strongest force guiding their movements. They were building, in their mind, the reality surrounding them and mapping their peri-personal space (Image 11). After a first moment of hesitation, they moved and opened themselves up to a wider exploration. Eventually, they met each other and they exploited all the energy, the power, and the beauty of the interaction generated by the cooperation of their bodies. They were part of a strong entanglement, corps who touch each other with no shyness (Image 12). This exhibition was characterised by an unusual approach to spatial elements. Whether these are people or things. Dancers were focused on their feelings and spent more time with those elements that did not belong to the semantics of a dance stage. Generally, they seemed more focused on the space embodiment than the performance itself.

Heartbeats

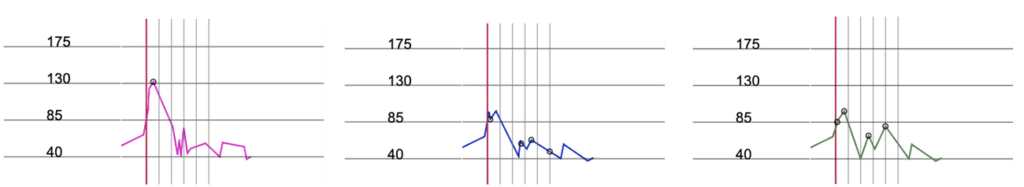

Emotions have diverse effects on autonomic nervous function, as illustrated by symptoms such as palpitations and hyperventilation. It is well documented that emotional processes result in changes in heart rate (HR), heart rate variability (HRV), and contractility. There is an interaction between neurons that fire upon increased attention and anxiety and neurons that control heart rate to discover the “why,” “how,” and “where to next” behind this phenomenon. In each of the above measurements, the green line symbolises the moment they reached the room. The RED line symbolises the moment the music starts: also the moment when the highest peak is recorded in all the cases (Music played as first is Time, by Pink Floyd). In general it is interesting to notice three aspects:

- All the peaks are recorded when they stumble into each other,

- There are frequent variations.

- The auditory and physical discontinuities allow a peak in the heartbeat when they don’t comply with the prediction.

Experiment: Performance With Open Eyes

Dancers entered the room blindfolded, and they got rid of the mask when the music started. One of them enjoyed the mask a bit longer. He seemed to know that once he could see, it would take over the performance. They don’t touch, they look. They turn 360 degrees, mapping the entire space (indicating they are now less interested in their peri-personal space). During this performance, the interaction with the other dancers was poor. They looked for an object, they seemed to look for a purpose or a reason. They moved aimlessly, looking for the right move to make. The space was explored and dwelt in all its dimensions. Dancers touched all the objects present, moved them, brought them around, and felt that they must use them all.

Heartbeats

In the below measures, the red line symbolises the moment they take off the mask, which was blinding. The space seen differs from the prediction, and we registered a high peak in the heartbeat. Variations are registered when an object falls or the music changes, not when they stumble upon each other. In general, in both performances, dancers kept their heartbeats in a normal range, besides some iconic moments, different in the two performances. The blindfolded one presented a pattern with more variations.

Final Interviews

At the end of the performances, dancers were asked to explain what they felt, if they had differences in feelings during the two performances, and, in case they had a preference between the two or they noticed notable differences in the space, to highlight them. They all loved and enjoyed the blindfolded experience more (Image 22).

Dancer 1: “Dancing blindfolded allowed a deeper exploration. During the performance with open eyes, everything was more about using and going through the object that I could see. When the dark is the only thing you see, you allow yourself to feel more and to be guided by that.”

Dancer 2: “While blindfolded, I was more focused on what I was touching. That was the driver of my further action. When I could see, I was constantly thinking about how I could use the objects available, how I could integrate them into the performance. They were two completely different dance performances, nothing was the same.”

Dancer 3: “I noticed a strong difference in the approach to the others. My level of alert was higher while blindfolded, I wanted to be aware of who I was touching. Action had an explorative intention, a will of understanding. When I could see them was more about delivering an image, making a choreography.”

Conclusions

According to Argiroffo and Cesari (2019), sight has always had a primary role, becoming dominant since human beings gained the upright position; this does not mean, however, that the other senses are not equally important or any less critical to perception and interaction with space. This study highlights how, although space exploration is wider and faster with open eyes, it becomes deeper and more immersive when vision is not in charge of the exploration. The blindfolded performance fosters a higher sense of embodiment, spontaneous movements, and richer social interactions. Rather than hesitance, the dancers exhibit curiosity, trust, fluidity, and sensuality, abandoning themselves to each other. The result is a captivating and emotionally resonant choreography. It is possible to conclude that the impossibility of making predictions allows for an impromptu space exploration and a fluid socialisation.

When sight is reintroduced, the focus shifts. Dancers are more interested in the choreography, so they prioritise spatial control, structured movement, and the visual composition of their performance. Social interactions persist but become shorter, less immersive, and more careful about the external appearance rather than the internal experience.

From a designing for learning perspective, this experiment highlights the power of sensory engagement in shaping experience and knowledge, stimulating curiosity, which becomes a design tool (Bar & Palti, 2017). Learning environments that intentionally manipulate sensory input, such as reducing visual stimuli to encourage tactile or kinaesthetic exploration, can foster deeper embodiment, creativity, and collaboration. Designing having in mind a multi-sensory engagement, it might be possible to encourage richer, more immersive learning experiences or, in some cases, generate new and undiscovered experiences.

Designing for learning happens through the creation of environments, activities, and experiences that improve the experience of people while acquiring knowledge, developing skills, or engaging with new concepts through space exploration. This study is an attempt to prove the importance of considering in design not only the sight and (maybe) the other traditional senses, but also starting to consider the seven remaining (Aeppli, 2013).

- Multi-sensory engagement, by leveraging different senses and types of perceptions rather than sight (touch, hearing, balance, movement, but mostly the sense of self and others), and therefore enhancing a deeper space exploration and understanding.

- Active participation, by encouraging hands-on, experiential learning rather than passive reception of information.

- Social Interaction by designing spaces and activities that promote fluid and friendly body exchanges and trust in each other.

- Adaptability and personalisation, by allowing for different space-exploration possibilities and abilities, but also ways of thinking.

- Exploration and play, by creating opportunities for curiosity, experimentation, and improvisation.

In the context of this study, designing means also structuring dance experiences that deliberately deviate from standard sensory inputs (such as blindfolding) to deepen spatial awareness, movement fluency, and interpersonal connection. It suggests that by focusing on a multi-sensorial perception, architects and designers can help users to learn, interact, and create from their bodies differently. Many famous architects—such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Peter Zumthor, Steven Holl, Daniel Libeskind, Álvaro Siza, and Kengo Kuma—have often integrated sensory experiences into their designs, creating spaces that engage multiple senses or even the full sensory spectrum. However, this approach is often overshadowed by a dominant modus operandi which privileges visual aesthetics, prioritising pre-conceived images of architecture over its multi-sensory experienceable potential. This approach is often requested and defended by the real estate market which aims to “sell images” complying to a visually based society which has its roots in the need to favour vision, the most immediate sense; but, mostly in educational buildings, it is essential to continually experiment and advocate for a more immersive and multi sensorial architectural vision—going beyond mere appearance to embrace the full depth of human perception.

Bibliography

- Aeppli Willi, The Care and Development of the Human Senses: Rudolf Steiner’s work on the significance of the senses in education, Paperback – April 15, 2013

- Argiroffo CG. Neuro-marketing of senses. Neuroscience.net. January 2019.

- Bar M, Palti I. Curiosity as a design tool: Final scientific report. Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture, Hay Grant Award. 2017.

- Barad K. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2007.

- Brancaccio N, Gattoni D, Niola F, Rozzi S. Wellbeing in the built environment: Federico Niola, Stefano Rozzi designing discontinuities between function and semantics. The Plan Journal. 2020;5:xx-xx.

- Grefkes C, Fink GR. The functional organization of the human motor cortex. Curr Biol. 2011;21(3):R151-R153. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.014.

- Fardelli, S. The Unseen. Pin Doc. Published 2019. Available from: https://www.pindoc.it/en/stefano fardelli/the-unseen.html.

- Feldman Barrett L. How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Mariner Books; 2017.

- Handjaras G, Ricciardi E, Lenci A, Pietrini P. Brain modeling of noun representations in sighted and blind individuals. Int J Psychophysiol. 2012;85(3):329-330.

- Hewitt A. Social Choreography. Durham and London: Duke University Press; 2005. Jackson D. Environmental entanglement. J Arch Educ. 2017;71(2):137-140.

- Mayer M. Pina Bausch: The Biography. London: Oberon Books Ltd; 2017.

- McGlynn S, Smith R, Alcock J, Murrain P, Bentley D. Responsive Environments. London: Elsevier Ltd; 1985.

- Potuoğlu Cook Ö. Beyond the glitter: Belly dance and neoliberal gentrification in Istanbul. Cult Anthropol. November 2006.

- Pallasmaa J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. 2nd ed. Chichester: Academy Press; 2012.

- Papale P, Chiesi F, Rampini P, Pietrini P, Ricciardi E. When neuroscience touches architecture: From hapticity to a supramodal functioning of the human brain. Front Psychol. 2016;7.

- Pillai T. Seeing, hearing, smelling, and the world. Howard Hughes Medical Institute; 1995.

- Ricciardi E, Bonino G, Sani L, Vecchi T, Guazzelli V, Haxby J, Fadiga L, Pietrini P. Do we really need vision? How blind people “see” the actions of others. Soc Neurosci. 2009

- Sincero Sarah Mae (2012). Measuring Emotions. Retrieved Apr 05, 2025 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/measuring-emotions

- University of Bath. How blind people see the world. Experiment. 2013.

- Wenders W. Pina: Dance, dance, otherwise we are lost. Film. 2012.

- Wascher, C.A.F., ‘Heart rate as a measure of emotional arousal in evolutionary biology’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2021, 376(1831), 20200479. doi: 10.1098/ rstb.2020.0479. Epub 28 June 2021.