Cities are incredible but they can also be intense. It is estimated that by 2050 70% of the global population will be living in cities.1 Despite the many benefits and opportunities that living in a city can offer, there are links between living in urban areas and increased risk of physical and mental health.2 Stress triggers which can negatively affect mental health and wellbeing include population density, pollution, noise, detachment from nature, demanding jobs and long working hours. High population turnover due to housing costs and renting can cause negative impacts by reducing attachment. At a community level, this can weaken social networks and erode feelings of trust and security, and at an individual level it can mean that people tend to not be familiar with, and benefit from, their local area, parks, community and support groups.3

In such dense and demanding cities, people need a place to slow down, notice their surroundings and take a moment for themselves. Spending time in places of tranquillity can help reduce stress and anxiety, increase contact with nature, reduce exposure to noise and pollution and can boost positive feelings and creativity.

However, tranquillity is typically associated with escaping the city. Finding regular time to do this can be difficult, due to perhaps busy schedules, and can be expensive.

So what happens when we challenge the mentality that tranquillity can only be found in the countryside, and celebrate tranquillity within our urban centres? Could the creation of a smart-city application help city dwellers seek and share moments of urban calm and actually be used to inform how we could design healthier cities, by integrating such spaces and experiences?

Concept

This article presents the concept and initial findings of Tranquil City, a non-commercial initiative exploring the meaning of tranquillity in London and promoting its wider consideration so that cities can better respond to human needs and promote healthier, happier lives. We are a team of environmental consultants with backgrounds in acoustics, air quality, sustainability, socio-economics, data science and geography.

How it works

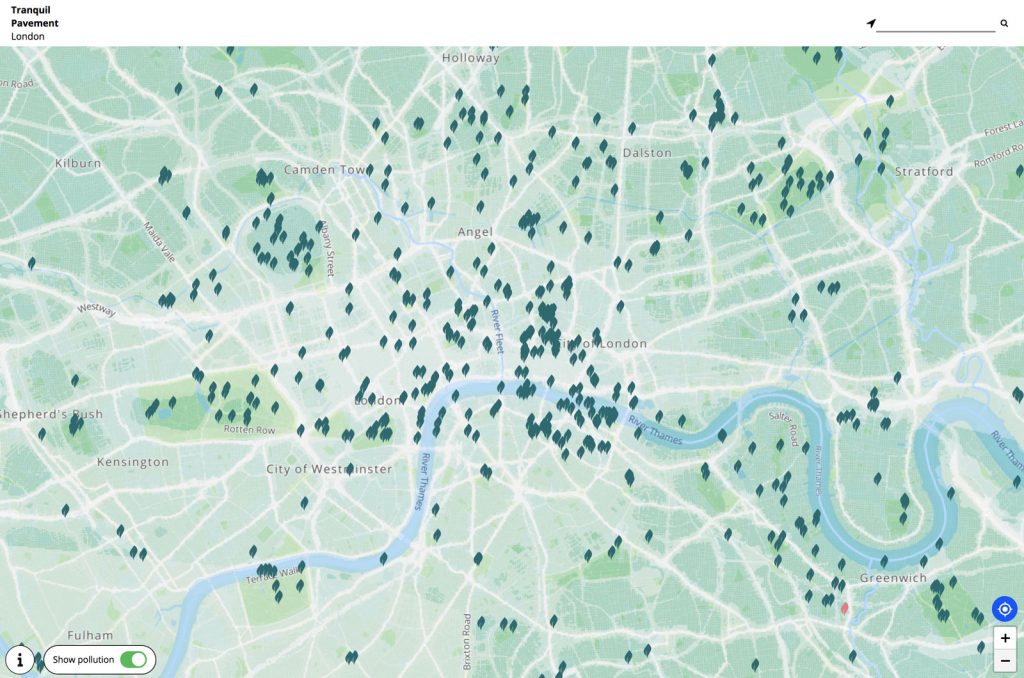

Through the #tranquilcitylondon crowdsourcing campaign, Londoners are celebrating and sharing their moments of calm in London via social media and thereby contributing to a map called the Tranquil Pavement. The map combines these personal and subjective data points with large public datasets on noise and air pollution, which provides users with a straightforward indicator of low pollution areas and streets. By conducting experiments with the Tranquil Pavement’s dataset and findings from a series of public walks and co-creation workshops, the project is beginning to gain a better understanding of the meaning of tranquillity in London for its inhabitants, and presents a method of identifying and protecting tranquil spaces by demonstrating their inherent social value, helping to inform planning from the bottom-up.

The tool encourages users to explore their surroundings and begin to use their own senses to aid navigation, such as focussing on soundscape, urban quality, nature and restorative environments, as opposed to speed. Our investigations suggest that these so-called ‘tranquil routes’ can have potentially significant benefits for people’s mental and physical health, by reducing exposure to pollution, and improving creativity, concentration and sleep.

Experiments

We began the crowdsourcing campaign in mid-2016, with the open question, “where do you find tranquillity in London?”. The only requirements were to post a photo or video to Instagram, along with a description, the location and to include the hashtag #tranquilcitylondon.

We applied to the OrganiCity Open Call shortly after.4 The Call was asking for ideas to take on London’s challenges, two being ‘Air Quality’ and ‘Urban Mobility’. Our proposal asked, ‘Is there a correlation between perceived tranquillity and low air pollution and noise?’ and, ‘Does travelling via tranquil spaces reduce our exposure to noise and pollution?’.

In order to begin at answering these questions we started by combining open datasets on noise and air quality, from Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Greater London Authority (GLA) respectively, using GIS software.5,6 We quickly realised that when the data was overlaid, the patterns were not clear and the engagement message could be lost. We decided to stay true to the concept that had driven us from the start of the project, which was to celebrate the positive and make this big data useful for the public. So we merged the noise and air quality data into a single indicator, and flipped the traditional pollution map on its head — instead choosing a colour scale that emphasised the low pollution areas, the ones that may lead us to discover more pockets of tranquillity, leaving the polluted areas to blend softly into the background.

We were keen to understand and document the benefits of tranquil spaces to our cities and city dwellers, as well as ways in which it may fit into the planning system. Our research highlighted a simple, but significant fact: that the protection of tranquillity is included in the UK planning system. The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) states that planners should “identify and protect tranquil areas which have remained relatively undisturbed by noise and are prized for their recreational and amenity value for this reason”.7 The only issue with this is that there is no sure way of identifying tranquillity in a purely objective sense. But the statement does bring the term ‘tranquillity’ into the context of the city, where it states that these areas may have remained ‘relatively’ undisturbed by noise, not the absolute absence of noise or the completely rural.

When the subjective #tranquilcitylondon posts were analysed in relation to their noise and pollution exposure, it was clear that these spaces were generally exposed to lower levels of pollution than the typical images of London (High Streets, transport Interchanges, tourist areas etc.). However, there was certainly a degree of the ‘relative’ at play in the perception of tranquillity, as there was notable crossover between areas deemed ‘non-tranquil’ and ‘tranquil’.

We held a workshop in February 2017 at the Future Cities Catapult to explore how the Tranquil Pavement could change the way people choose to navigate the city. We asked participants to draw on a map their normal A to B route, and then asked them to experiment with finding an alternative that focussed on the tranquil spaces and less polluted roads. ‘Tranquil routes’ were exposed to up to 50% less noise and pollution than the typical journeys that were generally based on speed or familiarity.

We were invited to Green Sky Thinking Week 2017 to run an event that would get people exploring, and would provide us a chance to demonstrate how the Tranquil Pavement could help people discover new places and alternative, greener and lower polluted routes.

We challenged ourselves, by choosing the heavily polluted Holloway Road to see if there was a better way of navigating it. We spent time exploring the area, discovering parks, secluded walkways, wildlife gardens and urban farms, finding a way to link them all. The ‘tranquil route’ provided a 60% reduction in average noise and air pollution exposure and over 65% of participants of the walking tours felt the route made them want to ‘slow down’, ’stop’ or ‘sit down’. Compared to the ‘non-tranquil’ route, the participants were significantly more likely to walk or cycle the ‘tranquil route’.

We were fortunate enough to have a second successful application to OrganiCity and this time decided to experiment with how our work could be complementary to Community Groups, Local Authorities, and Business Improvement Districts. We focused our efforts on three distinct areas of London; City of London, London Bridge and Deptford. We partnered with the John Evelyn Community Garden, Better Bankside, Team London Bridge, Lewisham Council and the City of London.

We teamed up with digital developer cooperative Outlandish to help turn the Tranquil Pavement GIS map into a living, growing and interactive tool for all to use. By early 2018, we produced the first interactive version, Tranquil Pavement V2.0, which we launched to the public with a workshop in order to gain an understanding of the following: whether it was useable and understandable; if it would encourage people to have the confidence to share their tranquil spaces; and whether people could discover new routes. We also asked users to vote for additional features that could be added to the tool — the abilities to highlight threatened spaces and share ‘tranquil routes’ won out.

In the following months, we hosted a series of engagement events to get people outside and discovering tranquil spaces in each of our focus areas. The walks enabled us to uncover some of the reasons why these spaces exist and the stories of the people who campaigned to create these spaces. We found that, in each of the areas, the places rated highest for tranquillity differed greatly. Gibbon’s Rent, just west of the new London Bridge Station, a quiet alleyway that has been lined with plant pots, secret seating and a pocket library shelf; Postman’s Park, a beautifully kept garden in amongst the City’s grey, grand structures that was a former burial ground and now the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice; and Sayes Court Garden, a quiet and reserved space which played a part in the creation of the National Trust.8,9

We also ran an event as part of Lewisham Council’s Air Quality Champion day, with 8-11 year olds who had been nominated to represent their classes in the fight for better air quality. We asked the question to the audience, ‘what is tranquillity?’ and received more diverse and thoughtful answers than with our older audience. Again, we presented each table with a printed version of the Tranquil Pavement and a challenge to find the ‘Tranquil Route’ between home and school (an example ‘home’ and ‘school’ was chosen). The children instantly understood the information.

This summer we have held events and talks with National Park City and the GLA, Green Sky Thinking, The Showroom, Carole Wright and as part of Ground Work Youth’s Inclusive Spaces week. Each of these events enable us to explore tranquillity in new areas of London, embellishing the Tranquil Pavement and making it more of a resource for people. By sharing these spaces with a new group of people each was able to offer their own insights, perspectives and relationships.

Initial findings and future

Tranquillity in London is diverse, as we all are as city dwellers, each having our own preferences and areas that we know. There are trends, of course — such as the significance of nature in an otherwise constructed city and relatively low levels of noise — but some are less obvious, such as the small pocket parks being those most noted for their tranquillity, perhaps due to the seclusion, the envelopment and/or the history of a place.

We have shown that tranquillity does, in general, relate to lower exposure to noise and air pollution, but the benefits are considerably greater than that. The thoughts, memories, perspectives and daily life stresses all play a part in the picture of tranquillity in London, and our cities generally.

Embracing tranquillity as a true part of our cities can help us have the agency to plan our daily routines to better our health and wellbeing, thereby improving the city overall.